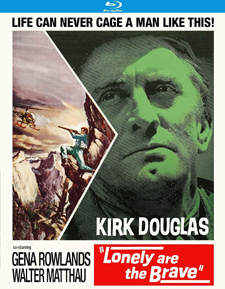

Lonely Are the Brave (Blu-ray Review)

Director

David MillerRelease Date(s)

1962 (May 19, 2020)Studio(s)

Universal Pictures (Kino Lorber Studio Classics)- Film/Program Grade: A-

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: B

- Extras Grade: B+

Review

A frequent movie plot puts the central character in a place, situation, or time period in which he feels misplaced and out of sync, and must cope with the unfamiliar while clinging to what he knows. Lonely Are the Brave is a contemporary western in which the ways of the Old West conflict with a mechanized, high-speed world.

Ranch hand and loner Jack W. Burns (Kirk Douglas) feels out of place in the modern world. The first image shows Jack awakened from a nap out in the open country by jet planes roaring overhead. His mode of transportation is his horse Whiskey, a loyal and constant companion. He carries no ID, respects no authority, has no permanent address, and thinks only of his friends and his horse.

Jack travels into Albuquerque to visit his friend Paul Boni (Michael Kane). Paul’s wife, Jerry (Gena Rowlands), tells Jack that Paul has been arrested for helping illegal aliens find food and work. Jack leaves Whiskey with Jerry and goes into town with the intention of picking a barroom fight, getting thrown into jail with Paul, and busting them both out. But with a wife and child waiting for him, Paul refuses to buy into Jack’s risky plan. Jack escapes alone, retrieves his horse and some food that Jerry has packed, and makes for the mountains—his ultimate destination Mexico and freedom. Sheriff Morey Johnson (Walter Matthau) leads the manhunt to find him.

Douglas, a true movie star, is on screen for most of the picture and easily carries it, with the unlikeliest co-star of his career. He convinces us that Jack Burns still subscribes to the code of the Old West, where the land is unfenced, men survive on their wits and brawn, and honor is not necessarily measured in following the law. His face deeply tanned from working outdoors, his attire pure cowboy, courtly toward women, loyal to friends, and unafraid to stand up to tough guys, Jack lives by a self-determined sense of morality and refuses to be constrained by any form of authority. Jack is reminiscent of Gary Cooper’s screen persona—little talk, action when necessary.

He’s an anachronism, as shown in a harrowing moment when he has to cross a highway on Whiskey and the horse, frightened by the speeding cars, panics in the middle of the road. They make it across in a scene that metaphorically contrasts the past with the present. Douglas performed many of his own stunts, some of which look truly dangerous, especially surmounting a steep slope on the mountain range.

The screenplay by Dalton Trumbo, based on The Brave Cowboy by Edward Abbey, keeps the dialogue to a minimum, allowing images to tell the story. Director David Miller juxtaposes sweeping black-and-white widescreen shots of landscapes with the noisy rattling and grinding of trucks, cars, and a helicopter—contrasting the peaceful wide-open spaces with fenced properties, paved roads, and modern vehicles with their roaring engines.

Lonely Are the Brave was Kirk Douglas’ favorite film. Not successful when originally released, its stature has grown through the years and is now considered a classic of 1960s cinema. Featuring supporting performances by George Kennedy, Carroll O’Connor, and William Schallert, the film is an interesting variation on the chase film. Director Miller builds suspense as we watch Jack elude capture by escaping to turf he knows much better than his pursuers. On a simple level, the film is about old ways vs. new ways, but it’s also the story of a man who values freedom above all else and is willing to sacrifice everything to hold onto it.

The Blu-ray from Kino Lorber Studio Classics release, featuring 1080p resolution, is presented in the aspect ratio of 2.35:1. Philip Lathrop’s black-and-white cinematography looks spectacular on the wide screen, with the ridges, outcroppings, and trees of the hills well defined. Many of his shots, reminiscent of Ansel Adams’ photographs, portray the majesty of the Sandia Mountains. Jack’s deeply tanned face and Jerry’s soft, almost glowing complexion contrast in the kitchen scene. Lathrop’s compositions favor expanses of untouched land interrupted by artifacts of the modern world—highways, a pile of junked cars, barbed wire fences, police cars, and a helicopter. The bars of the cell that surround him on three sides literally fence this cowboy in. The climactic scene, which takes place in a heavy downpour at night, is foreboding. We see early in the film how Whiskey is spooked trying to cross a highway in the daytime. Now it’s dark and raining, visibility is poor, and the road is the last obstacle between Jack and Mexico. Scenes in Sheriff Johnson’s office are gloomy and confining compared to the expansive outdoors that Jack prefers. Another visual contrast is the elegance and quiet with which Jack leads Whiskey through the mountain trails and the noisy, clattering, bouncy jeep that Johnson drives. The low-angle shots of Whiskey climbing the steep, rocky hills are suspenseful, as we’ve come to love the horse and we’re concerned for her safety.

The DTS High Definition Master Audio soundtrack is presented in English mono 2.0. Dialogue is clear and distinct in both indoor and outdoor scenes. The most impressive moments involve Jack leading Whiskey up the steep hills. The horse does its best but often loses her footing as dislodged rocks tumble downhill toward the camera, sounding louder and louder. The helicopter’s rotors pierce the silence and the pilots radioing their position appear to have Jack trapped. A couple of gun shots are unusually loud. Whiskey’s stubbornness is underscored by her frequent grunts as her hooves strike the stony trails. The barroom fight contains sweetened sounds of a bottle hitting a wall, a glass shattering, men grunting, furniture overturning, punches landing, and bodies hitting walls and floor. Goldsmith’s score varies from traditional western motifs to quiet moments to Jack’s theme—the lone melancholy trumpet.

Bonus materials include an audio commentary, the featurettes Lonely Are The Brave: A Tribute and The Music of Lonely Are the Brave, and several theatrical trailers.

Audio Commentary – Film historians Howard S. Berger and Steve Mitchell share their thoughts on the film. When Kirk Douglas read the original novel, he fell in love with the character of Jack W. Burns and the theme: “If you try to be an individual, society will crush you.” He was always drawn to the ideas in films. Douglas’ “charming, charismatic performance” is one of his best. He got into producing films early under his Bryna Company banner, including Paths of Glory and Spartacus. The film echoes of traditional westerns but without tired clichés. Metaphors are established early in the film as Burns keeps encountering boundaries (the barbed wire fence, the highway, the authorities). Writer Edward Abbey is anarchistic in his views. In the book, Paul is in jail for avoiding the draft. Bill Raisch, who plays a belligerent one-armed bar patron, lost his arm during World War II. He was Burt Lancaster’s stand-in and, with a prosthetic arm, appeared in Spartacus as a gladiator whose arm is cut off. He later starred as “The One-Armed Man” in the TV series The Fugitive. Rejected titles for the film include In Fury Bred, Rugged Justice, Wild Gun, Wild Heart, Forked Trail, and The Granite Cage. Douglas himself preferred The Last Cowboy. The film is artful without being artsy. In his memoir, Douglas wrote that he regretted hiring David Miller as director because he wasn’t up to the talents of the rest of the cast and crew. The camera is always active because Burns is constantly moving. Universal released the film without fanfare and it did such poor business that the studio pulled it from theaters. Lonely Are the Brave is now thought of highly, and many critics and historians regard Douglas, who died early in 2020 at age 103, as a “socially relevant producer and actor.”

Lonely Are the Brave: A Tribute – Kirk Douglas, Gena Rowlands, Michael Douglas, and Steven Spielberg discuss the legacy of the film. Kirk Douglas jokingly notes that his only regret is that “Whiskey stole the picture.” Spielberg says that, seeing the movie as a kid, he wasn’t that impressed since it didn’t have a lot of action. As an adult, he saw the textures in the screenplay and came to embrace it. Douglas, who often played a villain in movies, was playing against type as Jack Burns, a quiet, introspective man. Jack is a “magnificent anachronism.” Douglas liked the role because Jack is a good guy. The relationship between Jack and Jerry is naturalistic. Director of photography Philip Lathrop creates subtle changes in the cinematography. Interwoven with the interviews are clips from the film and behind-the-scenes production photos. Lonely Are the Brave has become “almost a cult film.”

The Music of Lonely Are the Brave – Soundtrack producer Robert Townson discusses the contributions of Jerry Goldsmith’s score. Goldsmith was recommended by Alfred Newman. Newman had never met Goldsmith but was impressed by his music for the TV anthology show Thriller. Various scenes are shown to illustrate the different approaches Goldsmith uses. He begins the film with a rousing fanfare under the Universal logo and title credits, suggesting a traditional western, and then transitions to more introspective music when we first see Jack lying against the rocks, napping. The music goes deep into characterization. A lone trumpet provides a melancholy sound, which is Jack’s theme. When Jack rides Whiskey across a river, the music is bold and expansive. Both “striking and sophisticated,” the score was written at the beginning of Goldsmith’s career. Music for the finale of the film was composed but was not used. We see and hear the finale with that music.

Trailers – Six theatrical trailers are included: Lonely Are the Brave, The Vikings, The Devil’s Disciple, A Child Is Waiting, Charley Varrick, and Midnight Lace.

– Dennis Seuling