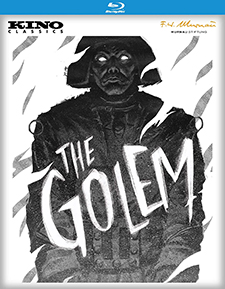

Golem, The (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Paul Wegener, Carl BoeseRelease Date(s)

1920 (April 14, 2020)Studio(s)

PAGU/Universum Film/Famous Players-Lasky Corporation (Kino Classics)- Film/Program Grade: B-

- Video Grade: B

- Audio Grade: A

- Extras Grade: A

Review

The Golem, together with The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, introduced German expressionism to cinema with its nightmarish images, heavily stylized sets, and sense of foreboding. These silent films inspired such classic horror movies as The Phantom of the Opera and especially Frankenstein. Writer/director Paul Wegener draws upon folklore, history, and the supernatural in this tale of a creature brought to life from mounds of clay to protect the Jewish inhabitants of Prague from persecution.

Suffering under the tyrannical rule of Rudolf II in the 16th century, Rabbi Loew (Albert Steinruck) makes a deal with an evil spirit to bring the Golem (Wegener) to life. In an elaborate creation sequence, the rabbi first shapes mounds of clay into the form of a large human-like creature, reads from an ancient book of sorcery, consults astrological signs, and affixes an amulet that causes the creature to open its eyes and lumber about. Obedient to Rabbi Loew at first, doing chores and serving as bodyguard to the residents of the ghetto, the creature eventually shows a violent side. The rabbi loses control of his creation and must deal with the consequences.

The Golem is an excellent example of German silent filmmaking. Architect Hans Poelzig fashioned highly stylized sets to represent the city of Prague in the Middle Ages. With its twisted staircases, misshapen buildings, crooked streets, curved walls, and arched windows, the film has a dreamlike appearance, since recognizable objects are not quite as they should be.

Looking like a page out of a vintage fairy tale book, The Golem also introduces an enigmatic being with a dual personality. Compliant and docile in one scene, it can bare its teeth and become violent in the next, making it unpredictable and adding suspense. The Golem is gentle in a scene with young children gathering around it, and later uses his superhuman strength to topple the palace.

The similarities to James Whale’s Frankenstein, made eleven years later, stand out. The Golem is a mute creature, it is brought to life through unorthodox methods, it has brute strength, walks awkwardly, turns on its creator, kills, carries off a beautiful woman (Miriam, the rabbi’s daughter), and its creator has an assistant. Wegener also infuses a bit of pathos into the creature, portraying the Golem as a victim of its own creation.

For a monster film, however, The Golem is not very scary. More of a tale based in Jewish folklore than an excursion into terror, it is more notable for introducing elements that later filmmakers would incorporate into stories of genuine horror. The “monster” here lacks an appearance that instills fear. He’s big and solemn-faced, but his weird pageboy hairdo looks like a toy tunnel from a Lionel train set, making it hard to take him seriously. For a contemporary comparison, think of Nosferatu, made two years later. The make-up on the vampire in that film is truly chilling, with his bald head, claw-like hands, long nose, pointy ears, and elongated middle teeth. His gaunt, nearly skeletal body completes the picture of a desiccated human creature.

Featuring 1080p resolution, The Golem is presented by Kino Classics in the aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The film is tinted, with original black-and-white footage colored according to the scene. A fire sequence, for instance, looks terrific with its red hue giving the flames intensity. Outdoor scenes are generally tinted blue and indoor scenes vary according to the dramatic moment. For a film this old, the picture is pretty sharp. According to introductory information onscreen preceding the film, “No original German copy of The Golem has survived. Two original negatives, filmed from different angles, were assembled from the exposed negative material. For the 1921 US release, negative ‘A’ was shortened considerably.” There are light scratches, mostly on the right, some emulsion spots, and a few ingrained dirt specks. However, there are no annoying splices or jump cuts because of missing footage. The look of the film is impressionistic, particularly the architecture, both inside and outside. This is one of the film’s strong points. Irregular walls, oddly angled buildings, narrow winding staircases, twisted alleyways, and enormous claw-like hinges on doors give The Golem an otherworldly atmosphere. The cinematography is by Karl Freund, whose cinematography captures the elegance of the royal court with its fancy-outfitted courtiers and the poverty of the ghetto with its narrow, claustrophobic streets. Freund would later be the director of photography on Dracula in 1931. His close-ups of the Golem fail to convey terror, since Wegener’s make-up is more peculiar than frightening. The print contains the original German intertitles with English subtitles.

The three scores are each presented in 16-bit LPCM 2.0. They were composed by Stephen Horne, Admir Shkurtaj, and Lukasz “Wudec” Poleszak. All three add atmosphere and make watching this silent film much more enjoyable.

Bonus materials include an audio commentary, a comparison of the German and US release versions, three musical score options, and the US release version (with a fourth score).

Audio Commentary – Film historian Tim Lucas refers to The Golem as the “granddaddy of all horror films.” The version in this release was restored by the F.W. Murnau Foundation. The film was conceived and directed by its star, Paul Wegener, who had studied to be a stage actor. He directed and starred in the silent feature The Student of Prague and, while in Prague, heard legends about the Golem. He set The Golem in medieval Prague and told a fantastical tale with a basis in historical fact. While Rabbi Loew studies the stars to prepare a horoscope for the emperor, he sees portents of coming disaster. The unusual production design is based on “organic architecture,” in which structures resemble human lungs and chambers of the heart. The film is constructed episodically, in five distinct chapters. The invocation sequence involved many early special effects, which are explained in detail. Later comic book characters such as the Hulk and Iron Man (with an electromagnet embedded in his chest) are flashier variations of the Golem character. The Rose Festival sequence is reminiscent of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death, in which the privileged nobles, isolated from the outside world, enjoy their revelry as the populace faces disaster. The Golem is touched when a courtier gives him a flower. “Horror fantasy specialist” Wegener made an earlier version of The Golem in 1915 and starred in many fantasies, relying a lot on special make-up. A theme of The Golem is life is a gift, even when that gift becomes a struggle.

Comparison of German and US Release Versions – This is a side-by-side comparison of the 1995 Cinetek di Bologna restoration and the F.W. Murnau Foundation restoration. The Bologna version uses footage from several archives with additional restoration and digitization occurring in 2003. The Bologna version is on the left, the Murnau version on the right. Facial expressions are clearer and details better delineated in the Murnau version. Some scenes feature different camera angles and different takes. Some shots are matted in the Bologna version and shown full-frame in the Murnau. Costumes and sets reveal details far more clearly in the newer restoration. In the Bologna version, the Golem looks metallic. Often, faces and objects in the Bologna version appear overexposed, with details lost.

US Release Version – The American release runs about an hour and features a score by Cordula Heth. Scenes from the German version are rearranged and edited. Because of the absent footage, the pace is faster.

– Dennis Seuling