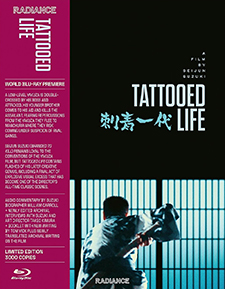

Tattooed Life (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Seijun SuzukiRelease Date(s)

1965 (September 24, 2024)Studio(s)

Nikkatsu (Radiance Films)- Film/Program Grade: B+

- Video Grade: A-

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: B+

Review

Seijun Suzuki’s Tattooed Life (Irezumi ichidai, 1965) is also known under its more directly translated title, One Generation of Tattoos as well as White Tiger Tattoo, which was the title Toho International gave it when they distributed it abroad on behalf of Nikkatsu Studios. Under any title, however, this is an above-average if by-the-numbers yakuza-on-the-run action melodrama.

The I’ve-seen-this-story-before finds two brothers on the lam. One is a tough, handsome yakuza lieutenant, Tetsutaro “White Tiger Tetsu” Murakami (Hideki Takahashi), trying to keep his pimply younger brother, Kenji (Kotobuki Hananomoto), out of a life of crime and into art school. However, as the film opens, Tetsu is double-crossed and Kenji commits murder to save his older brother’s life. After laboriously talking Kenji out of turning himself in to the police, Tetsu suggests they flee to pre-war Manchuria (the film is set around 1927), but in a small port city lose their passage money to a con artist, Senkichi Yamano (Hosei Komatsu).

Penniless (yeniless?), the two find work as laborers digging a large tunnel for the construction of a dam. Kenji becomes obsessed with sculpting a figure in the image of the boss’s wife, Masayo (Hiroko Ito). Meanwhile, Masayo’s perky younger sister, Midori (Masako Izumi, very cute), falls in love with Tetsu, though he keeps his yakuza tattoos (and therefore his true identity) tightly hidden under a shirt he never takes off, even when bathing.

Perhaps what’s most interesting about Tattooed Life is just how cagily it is structured for Nikkatsu’s mostly working-class audience. The brothers aren’t accepted at the construction site at first, winning their respect only after Tetsu takes on foreman Tsunekichi (Nikkatsu/Suzuki regular Kaku Takashima) in a Quiet Man-type epic brawl. In the tradition of Hiroshi Inagaki’s Tatsu (Doburoku no Tatsu), whose similar tale had been a big hit three years before, the working stiffs are the heroes, and their back-breaking work cut off from the rest of society bonds them together. Not surprisingly, one of the villains is a college-educated turncoat (Osamu Ezaki, another Nikkatsu staple).

Far too many Japanese movies are unfairly likened to American Westerns, but in this case the comparison is apt. The tunnel workers might just as well be cowboys herding cattle; there’s an almost Western-style saloon and an old-time "wanted" poster turns up and is used to implicate Tetsu and Kenji in an act of sabotage. The picture is rife with subplots and, typical of such stories, naïve Kenji and his dreamy-eyed notions emotionally shackle the more pragmatic Tetsu, the younger brother so constantly mucking things up he becomes an intensely irritating character well before the movie is over.

More Suzuki films are available in the west on DVD and Blu-ray than perhaps any other Japanese director expect maybe Kurosawa. Tattooed Life isn’t exactly scraping the bottom of the barrel, but there isn’t much directorially that stands out, either. Suzuki uses jump cuts for labored effect: for instance, a night shot of two docked boats jumps to daybreak with one of the ships now mysteriously absent. And, as usual for the director, bright splashes of color are used—in this case a blood-red thunderstorm storm lights up the sky for the blazing climax—but otherwise Suzuki’s direction is not measurably better than other genre filmmakers of his generation. The heavily-stylized climax is impressive, notably when Tetsu barges through a series rooms with brightly-painted fusuma (sliding doors), but even that seems lifted from Roger Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death, released the year before. He certainly doesn’t even work up much energy for the picture’s singularly Oedipal tension between Kenji and Masayo, the brothers orphaned years before.

Takahashi was a prolific (eight films a year) but not especially charismatic Nikkatsu star, and the most striking thing about the young man playing his brother is the actor’s notably peculiar name. Sharp-eyed viewers will note the presence of genre star Seizaburo Kawazu playing his stock yakuza godfather character in a “guest star” spot, while Akira Yamauchi, the scientist in Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster, plays Masayo’s hard-to-read husband. Stealing the film though is Komatsu’s grifter. With his three-piece white tropical suit and bright red shoes, the actor is memorably slimy, coming off as a kind of Japanese Strother Martin. (He later moved to Toei, appearing in such films as Female Convict Scorpion: Jailhouse 41.)

Radiance’s Blu-ray, Region “A” and “B” encoded, and provided by Nikkatsu, presents the film in its original 2.35:1 Nikkatsu GrandScope aspect ratio. The image is impressively sharp with excellent color and contrast throughout. The uncompressed, 2.0 LPCM mono (Japanese only) is strong for what it is, and the optional English subtitles are good, with the exception of one odd mistake:

While the construction company in the film is clearly “Yamashita,” the subtitles wrongly assume Midori, Masayo, and her husband are also named Yamashita. In the movie, Kenji, for instance, typically addresses Masayo as “Okusan,” used to refer to someone’s wife, while the subtitles for this read “Mrs. Yamashita” or some variance. However, the name of the family is clearly not Yamashita but Kinoshita. Nikkatsu’s own credits confirm this, and Radiance gets this right in the booklet’s cast and crew list, just not in the English subtitles.

The good extras consist of an audio commentary by William Carroll, author of Seijun Suzuki and Postwar Cinema; archival video interviews with Suzuki and art director Takeo Kimura; a trailer; and a 20-page booklet featuring an essay by film curator Tom Vick and a 1965 review of the film by Tetsuya Fukasawa, originally published in Kinema Jumpo.

Though entertaining enough as a program picture, most of Tattooed Life’s imagination went into its fun main title design rather than its tired script. Suzuki doesn’t rise above the material, but rather plods through it.

- Stuart Galbraith IV