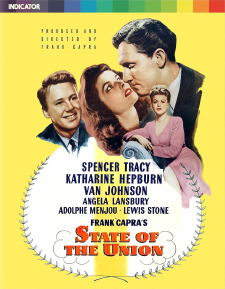

State of the Union (Region B) (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Frank CapraRelease Date(s)

1948 (March 27, 2023)Studio(s)

Liberty Films/MGM (Indicator/Powerhouse Films)- Film/Program Grade: A-

- Video Grade: A-

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: A

Review

[Editor’s Note: This is a Region B-locked Blu-ray import.]

Frank Capra’s film of the 1945 Russel Crouse/Howard Lindsay Pulitzer Prize winning play of the same name, State of the Union (1948) is an unusual, intriguing mess, a political drama (with comic elements) that at times is perceptive and prescient, while unpardonably pandering, sentimental, and illogical in other ways. The film has many unusual, even unique components. It’s a Spencer Tracy-Katharine Hepburn film, but only because Claudette Colbert pulled out at the last minute, resulting in Hepburn playing a very un-Hepburn like character—a stay-at-home wife and mother whose husband is openly cheating on her.

Hollywood political films generally steered clear of even identifying which political party its main characters belong. State of the Union not only revolves around the explicitly Republican campaign of a dark horse candidate, it’s specifically the then-current 1948 Presidential race opposite Democratic incumbent Harry S Truman. (Truman, of course, ultimately upset the real-life eventual Republican contender, Thomas E. Dewey.)

It’s obvious Capra was harking back to his populist heroes of the 1930s—Mr. Smith, Mr. Deeds, etc., and the film awkwardly makes changes to the play to reflect this. But those earlier films were scripted by leftist writers like Sidney Buchman and especially Robert Riskin. For State of the Union, the increasingly politically conservative Capra hired Myles Connolly and Anthony Veiller, who seemed to share Capra’s politics, at least based on their (separate) later work on two of the most hysterical anticommunist films of the 1950s: My Son John and Red Planet Mars. Yet, politically, the film is all over the map, with Tracy much of the time coming off more like a 1940s Bernie Sanders, Democratic-Socialist type.

In a role almost prefiguring her single-minded Machiavellian character in The Manchurian Candidate, Angela Lansbury is cold and calculating newspaper tycoon Kay Thorndyke, who talks Republican strategist Jim Conover (Adolphe Menjou) into testing her proposed dark horse candidate—self-made aircraft tycoon Grant Matthews (Spencer Tracy), with whom Thorndyke is having an affair.

Matthews is very reluctant to join the race, but finally persuaded to embark on a cross-country speaker tour to test the waters, accompanied by cynical newspaper reporter-turned-campaign manager Spike McManus (Van Johnson). For appearances sake, the campaign needs the public participation and support of Matthews’s estranged wife, Mary (Katharine Hepburn), who, despite her awareness of Matthews’s relationship with Thorndyke, agrees to play along, hoping that through her sincere support and belief that her husband would make a great President, hopes she might win him back in the process.

Matthews, at first, speaks freely, going off-script and ignoring the canned, generic (and pro-big business) speeches Conover provides. Appealing to “plain folks,” these speeches go over like gangbusters with the hoi polloi, but if Matthews has any chance of actually winning the nomination, he must agree to backroom deals with repugnant business leaders and special interest (including openly racist) types. Behind-the-scenes, Thorndyke assures these influence peddlers that she, not Matthews, is the real power behind the hoped-for throne.

Somehow, in trying to adapt State of the Union along populist yet right-leaning Republican lines, Tracy’s character comes off as more Democratic-Socialist than anything else, while the cynicism expressed by those played by Menjou, Lansbury, and others is unexpectedly, nakedly honest and revealing in ways that play timelier than ever.

Here’s one such example, expressed by Matthews: “The wealthiest nation in the world is a failure unless it’s also the healthiest nation in the world. That means the highest medical care for the lowest income groups.”

In another scene, Conover dismisses the strong positive reactions by ordinary folk to Matthews’s speeches, including scads of enthusiastic telegrams because, according to Conover, voters don’t pick the candidate, the party and its delegates do. (Menjou may have been a fanatical right-winger, but as an actor he’s very good throughout, impatiently explaining things to Matthews that, to him, are absurdly obvious.) In another scene, Matthews wonders if there’s any difference between the two parties, to which Conover responds, “There’s all the difference in the world—they’re in and we’re out!”

On one hand, the script tries positioning Matthews-Mary and Conover-Thorndyke as conventional Hollywood-imagined opposite extremes, Matthews dispensing populist, naïve homilies while Conover and Thorndyke are blatantly corrupt hypocrites. And yet, as if by accident, each side inadvertently often speaks the truth: Matthews espouses positions and programs popular with ordinary Americans that neither party would ever actually get behind because they run counter to those held by all the big business and special interest groups really running the show.

Unfortunately, State of the Union is ultimately very clumsy, ham-fisted, and obvious in other ways. For starters, beyond the fact that 22-year-old Angela Lansbury is egregiously miscast as a ruthless newspaper baron, that Matthews would fall for such a heart-of-stone she-devil in the first place is simply not credible on any level, and the screenplay makes no effort to persuade the audience how any attraction is even possible. Matthews’s switch to the Dark Side, from reluctant candidate insisting on doing things his way to a man willing to pay ANY price to get elected likewise makes no sense. Similarly, his abrupt turnabout at the climax, in which a contrite Matthews repeatedly apologies to his followers and keeps insisting he’s a “loser” is a real letdown, begging more questions than it resolves. We expect Tracy to play a paragon of virtue, but State of the Union’s finale pointlessly and depressingly portrays Matthews as a quitter—he simply gives up, a disillusioned, defeated idealist.

This is the kind of film where many of its flaws aren’t immediately apparent because the cast does such a fine job selling the material. Tracy is excellent as usual but I found myself more impressed by Hepburn, playing against type as the dutiful wife, willing to endure one humiliation after another because she so believes in her husband and the greater good he can bring to the country. Van Johnson takes an overly familiar stock character and makes him believable and interesting as a human being. Also cast against type effectively is Lewis Stone, pillar of wisdom Judge Hardy from MGM’s Andy Hardy series, as Thorndyke equally cold-blooded father. He’s gone after the opening scene yet his prominent billing is definitely earned. Many of the bit players have good moments—and are handed most of the comedy—but Capra’s approach to these “little people” on the sidelines is just that; they’re depicted almost to a one as rubes and semi-literate hicks. The difference between how these small parts play here versus, say, in It’s a Wonderful Life is almost shocking, as if Capra shared Conover’s contempt for the unwashed masses.

The complex financing for State of the Union, a co-production of Capra’s Liberty Films and MGM, resulted in the film changing hands several times following its original theatrical run, finally landing with Universal. Powerhouse Films/Indicator’s Region “B” release was forced to use film elements with opening and closing title cards from a later reissue, titles so ugly and amateurishly done they managed to misspell the names of Katharine Hepburn and Adolphe Menjou, among others. The original MGM titles, albeit in battered condition, are included as an extra feature. Otherwise, the transfer looks great, the 1.37:1 standard, black-and-white film appearing pristine, with superb detail and excellent contrast. The LPCM mono audio is also very strong for a picture from this era. For this review we were provided with a Region “B” locked check disc, with no packaging or booklet. The booklet reportedly includes a new essay, archival interviews with Capra, contemporary reviews, and other material.

Extras on the disc include a very informative and observant audio commentary track by Claire Kenny, Glenn Kenny, and Farran Smith Nehme; a 1973 audio interview with Lansbury with Rex Reed at the National Film Theater; a new video essay on Lansbury by Lucy Bolton (29:00); the aforementioned original opening and end credits (2:28); an image gallery; and a trailer (2:54).

State of the Union is a polished, entertaining production; even at more than 122 minutes (unusually long for a Hollywood movie from 1948) it never gets dull. It’s strange contrasting mixture of sophistication and “Capracorn” is both fascinating and frustrating, but it’s a very worthwhile film, almost essential viewing even. Highly Recommended.

- Stuart Galbraith IV