Exorcist, The: 50th Anniversary Ultimate Collector’s Edition Steelbook (UK Import) (4K UHD Review)

Director

William FriedkinRelease Date(s)

1973 (October 20, 2023)Studio(s)

Hoya Productions/Warner Bros. (Warner Home Video)- Film/Program Grade: See Below

- Video Grade: A-

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: A+

- Overall Grade: A

Review

While there have been plenty of horror films throughout cinematic history that have been landmarks of the horror genre, only a few of those can be considered as broader cultural landmarks that have transcended genre and tapped into something more universal. The Exorcist is one such film, since its cultural reach far transcended the bounds of typical horror fandom. While Warner Bros. had no faith in the film (no pun intended) and tried to dump it in late December on a small handful of screens, The Exorcist quickly became a phenomenon that lasted for a whopping 105 weeks at the box office, forcing the studio to expand its release in order to keep up. Audiences were lining up around the block to see it, quite literally so, regardless of how unpleasant that the winter weather may have been. The Exorcist was the “It” movie of 1973 that remained an “It” movie for the next two years as well. Yet to understand why this religious-themed horror film touched that kind of cultural nerve, you need to turn not to original novelist William Peter Blatty, but rather to Stephen King. We’ll get to that in a moment, but let’s start with Blatty first.

Blatty’s inspiration for The Exorcist was a supposed real-life series of exorcisms that had taken place in 1949 (the actual events of which have been much disputed ever since then). Blatty was interested in spiritual struggle as a crisis of faith, with good ultimately triumphing over evil. Regan MacNeil’s possession by a demon and her eventual release from torment at the hands of Father Merrin and Father Karras resulted in the restoration of that faith, especially for Father Karras. In other words, the scandalous grotesqueries that Blatty imagined were a means to an end, not an end unto themselves. Still, thanks in no small part to the graphic details that he described in the book, The Exorcist became a runaway bestseller, so a cinematic adaptation seemed inevitable. Yet Blatty was only willing to sell the rights to the novel on the condition that he was retained as producer, because he wanted to ensure that his literary vision remained intact on screen.

Eventually, the project was set up at Warner Bros. with William Friedkin as director, and the rest became history—except that it really didn’t, because Blatty and Friedkin didn’t always see eye-to-eye. Friedkin was more interested in the visceral horrors of Blatty’s story, especially in terms of how the deepest of evils could be hiding in plain sight under the banal suburban environments of Georgetown. He was much less interested in the triumph of good over evil, and he excised Blatty’s “happy” ending from his final cut, as well as several other scenes that Blatty felt were crucial in order to convey the novel’s themes. At the time, that became a bone of contention between the two of them, although that wasn’t quite the end of the story. Friedkin eventually created an alternate cut that reincorporated the missing footage into something closer to Blatty’s intentions, which was released on home video in 2000 as The Version You’ve Never Seen and with further revisions, that version is now referred to as the Director’s Cut (even though it would be more accurate to refer to it as a producer’s cut).

For now, however, let’s go back to 1973 and the original theatrical release of The Exorcist (although we’re going to take a small detour to 1981 along the way). Why, exactly, did The Exorcist become such an unprecedented success that it transcended the horror genre and became a cultural touchstone? Was it because audiences were interested in having their own faith reaffirmed alongside that of Father Karras? Spoiler alert: no, not really. The Exorcist may be a religious-themed horror film, but it’s not necessarily the religious elements that touched a cultural nerve—at least, not in the way that Blatty intended. To understand that, we need to turn to Stephen King and his indispensable 1981 guide to the horror genre, Danse Macabre. King saw The Exorcist as being “a film which relies on the unease generated by changing mores,” and felt that its box office success could only be understood in that context. The generation gap had been growing since the Sixties, with the social unrest of the era being led by the younger generation. For the older generation, the accompanying erosion of societal taboos was a very real fear that still hadn’t dissipated by the time that The Exorcist was unleashed in 1973.

In many ways, Regan MacNeil is the perfect embodiment of those fears. An otherwise normal, happy, clean-cut child is transformed into something truly transgressive. She spews obscenities, masturbates with a crucifix, and forces own mother’s head in her lap while screaming, “lick me!” At the same time, her cherubic face is transformed into a horribly disfigured, head-spinning monstrosity. For anyone concerned about the influence that rock & roll, drugs, and free love may have been having on the youth of the day, all of them put together had nothing on Pazuzu. Regan MacNeil represented the older generation’s worst fears made manifest. That’s one reason why a film about the triumph of good over evil and the restoration of belief appealed to the irreligious as much as it did to the faithful (although Friedkin’s intentionally more ambiguous ending certainly didn’t hurt). The fears that were being exploited were different in each case, but either way, very real buttons were being pushed.

Of course, the appeal of The Exorcist extended far beyond those demographics, but it that appeal still comes down to the transgressive nature of the film. The Exorcist broke many different taboos in primal fashion, and there’s no getting around the fact that many different kinds of people lined up around the block in order to experience its transgressiveness and live to tell the tale. Watching it back then was an endurance test that became a badge of honor. Whatever lofty goals that Blatty may have had for the story, Friedkin delivered the visceral thrills that kept audiences coming back for more.

In Danse Macabre, Stephen King posited a hierarchy for the horror genre with “terror on top, horror below it, and lowest of all, the gag reflex of revulsion.” Yet he resisted the idea of preferring one over the other in his own work, with each of them serving a purpose: “I recognize terror as the finest emotion… and so I will try to terrorize the reader. But if I find I cannot terrify him/her, I will try to horrify; and if I find I cannot horrify, I’ll go for the gross-out. I’m not proud.” The Exorcist exploits all three of these emotional responses, and Friedkin definitely wasn’t too proud to go for the gross-out. The film veers between terror, horror, and revulsion with wild abandon (or should I say wild Abaddon?) Taboos are both cultural and personal, and one person’s taboo may be another person’s tradition. The genius of Friedkin’s version of The Exorcist is that he took a story that broke taboos in the narrow context of Roman Catholic faith and found a way to break taboos that crossed religious, cultural, and even ethnic boundaries. That’s why it was so successful when it was first released, and that’s why it endures to this very day.

THE EXORCIST (THEATRICAL CUT): B+

THE EXORCIST (DIRECTOR’S CUT): B

Cinematographers Owen Roizman and Billy Williams shot The Exorcist on 35mm film using Arriflex 35 II-C and Panavision PSR R-200 cameras with Panavision Standard Prime lenses, framed at 1.85:1 for its theatrical release. (Roizman still shot the majority of the film, but Williams handled the location shoot in Iraq.) This version is based on a 4K scan of the original camera negative, graded for High Dynamic Range in HDR10 only. Note that aside from the additional footage and the extra so-called “subliminal” effects in the director’s cut, the basic master for both cuts is identical, so we’re going to treat them as one for the purposes of this review.

As usual, dupe elements had to be used for any optical effects like the opening titles and the burned-in English subtitles in the Iraq sequence, but setting those aside, everything looks as sharp as possible, and there’s no traces of remaining damage visible. There’s a definite increase in fine detail compared to the Blu-ray, especially in the sand and rocks of the Iraq sequence, and the grain is generally managed perfectly (with one noteworthy exception that we’ll get to in a moment). The Exorcist was shot on Eastman 5254 stock, but Roizman pushed it one stop for the interior sequences, so the grain in those shots should be slightly heavier, but in practice there’s not much difference between the two.

Now, let’s rip off the Band-Aid before we delve into this particular color grade: the reality is that The Exorcist has never had consistent grading throughout its entire tenure on home video, and this version is no exception. Fans can and will argue until they’re blue in the face regarding which grades are more “accurate” to the original release, but they really don’t know that with certainty. No one, and I do mean no one, can remember the specific color timing of release prints that they saw back in 1973. Human memory just doesn’t work that way (Patreon supporters will have access to an article on that very subject.) Worse, there’s no proof that release prints were accurate to the actual approved answer prints anyway. Unless you build a time machine and go back into the screening room with Friedkin and Roizman, you simply can’t say which version is the most accurate to their intentions back then—and you can’t trust their memories of those intentions, either. Friedkin and Roizman were involved with the various changing various grades in the past, and they’re credited as having supervised this 4K master, too.

So rather than wasting time on any of those arguments, I’m simply going to comment on how this grade looks when taken on its own merits. And it looks pretty impressive overall. The saturation levels have definitely been pushed higher than before—the orange/red sky after the opening credits is really orange now. Some of the highlights are pushed a bit too far, and the halation around the light sources when Father Karras is in the subway look blown out. Where things get a little odd is in the exorcism sequences. Roizman told American Cinematographer back in 1974 that those sequences were designed to look monochromatic in comparison to the outside world, and that effect has been replicated here, although the means for doing so have changed. It looks like Friedkin applied the same technique that he used for the much-maligned first Blu-ray of The French Connection: adding an oversaturated color layer to a black-and-white version of the film. The exorcism now has that same glowing, silvery pastel look to it that The French Connection did until fans (and Owen Roizman) had a fit about it. Yet in this case, it works much better. The textures and the grain do inevitably tend to smear a bit, but it still creates a cold, otherworldly feel that’s more or less true to Roizman’s intentions, though not his actual techniques.

Primary audio is offered in English Dolby Atmos for both cuts of the film, plus 2.0 mono DTS-HD Master Audio on the theatrical cut only. The Exorcist was released theatrically in mono, and the 2.0 track does appear to be the unaltered theatrical mix. The Atmos mix builds on the previous 5.1 remixes, but that’s like saying that an entire skyscraper was built on a basic foundation—there’s a world of difference between the two. This is a drastically altered mix, with myriad added sound effects, some of which have been repurposed from the original stems, and others are completely new additions. Many of them work quite well, although there are a few inexplicable additions like the sound of a jet airplane over the transition from Iraq to Georgetown. That said, like it or not, it’s a really impressive mix when considered on its own terms instead of comparing it to the original mono track. It’s wildly immersive, and the offscreen demonic noises have been moved around the soundstage to appropriate positions within the room—which makes the jump scares even more effective. The bass is significantly deeper, too, and that adds to the experience. (Note that while the Atmos tracks on the theatrical cut and the director’s cut should be identical, there are actually a few minor omissions on the director’s cut, like the sound of Tubular Bells being accidentally dialed out at one point.)

That said, it’s still best to think of the Atmos mix as being an optional alternate version. If you’ve never seen The Exorcist, the original theatrical mono mix is the only way to go for a first viewing. It won the 1974 Academy Award for Best Sound for a damned good reason. You’re not going to be able to do anything about any of the changes to the color timing of The Exorcist over the years, but you can at least experience it exactly as it was intended to sound. Yet once that’s out of the way, experiment with the Atmos track, because you just might like it if you can keep an open mind about it.

The only disappointment with this release, at least as far as the sound is concerned, is that it doesn’t include the older 5.1 mix anymore. That’s a shame, because it represented something of a middle ground between the theatrical mono and this new mix, and for anyone who finds the Atmos changes too distracting, it made a nice middle ground. But worse case, you’ve still got the mono to fall back on.

Additional audio options for the director’s cut include French (Canada), French (France), German, Italian, and Spanish (Spain) 5.1 Dolby Digital, plus Spanish (Latin America) and Czech 2.0 Dolby Digital. Subtitle options include English SDH, French, German SDH, Italian SDH, Spanish (Spain), Dutch, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Spanish (Latin America), Czech, Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish. Additional audio options for the theatrical cut include French, German, Italian, Spanish (Spain), and Spanish (Latin America) 1.0 mono Dolby Digital. Subtitle options include English SDH, French, German SDH, Italian SDH, Spanish (Spain), Dutch, Chinese, Korean, and Spanish (Latin America).

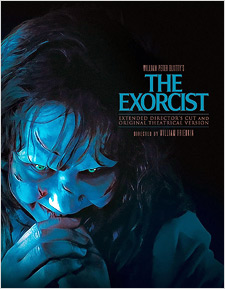

The Warner Bros. Region-Free Ultimate Collector’s Edition Steelbook Ultra HD release of The Exorcist in the U.K. is a five-disc set that consists of two UHDs and three Blu-rays. The UHDs are the same discs that were included in the North American 4K releases of The Exorcist, while the Blu-rays are identical to the previous Blu-ray versions, right down to the menu design—they haven’t been remastered for this release. There’s also a third Blu-ray with additional extras. All five discs are housed within a Steelbook that uses the theatrical poster artwork. The set includes six double-sided art cards, a double-sided lobby card, and a double-sided foldout poster. There’s also a 40-page booklet with unsigned essays, cast & crew bios, trivia, and a program for the Roman Ritual of exorcism. Everything is housed inside a rigid slipcase featuring new artwork—and no, it’s not the much-maligned artwork from the North American version, although it’s probably be no less controversial.

Warner Bros. really dropped the ball in the U.S. by releasing The Exorcist as bare-bones UHDs. Aside from the commentary tracks and the vintage introduction by William Friedkin, none of the rest of the previously available extras were included on disc. This U.K. set rectifies that issue, although the tradeoff is that there aren’t any Digital Codes included. Considering the quantity of extras, as tradeoffs go, that’s a pretty minor one:

DISC ONE: DIRECTOR’S CUT (UHD)

- Audio Commentary by William Friedkin

DISC TWO: THEATRICAL CUT (UHD)

- Introduction by William Friedkin (Upscaled SD – 2:11)

- Audio Commentary by William Friedkin

- Audio Commentary by William Peter Blatty with Sound Effects Tests

DISC THREE: DIRECTOR’S CUT (BD)

- Audio Commentary by William Friedkin

- Raising Hell: Filming The Exorcist (HD – 30:03)

- The Exorcist Locations: Georgetown Then and Now (HD – 8:30)

- Faces of Evil: The Different Versions of The Exorcist (HD – 9:52)

- Theatrical Trailers:

- The Version You’ve Never Seen (SD – 2:01)

- Our Deepest Fears (SD – 1:37)

- TV Spots:

- Most Electrifying (SD – :17)

- Scariest Ever (SD – :32)

- Returns (SD – :33)

- Radio Spots:

- The Devil Himself (HD – 1:04)

- Our Deepest Fears (HD – :35)

DISC FOUR: THEATRICAL CUT (BD)

- Introduction by William Friedkin (Upscaled SD – 2:11)

- Audio Commentary by William Friedkin

- Audio Commentary by William Peter Blatty with Sound Effects Tests

- Sketches & Storyboards (SD – 2:45)

- Interviews with William Friedkin and William Peter Blatty:

- The Original Cut (SD – :55)

- Stairway to Heaven (SD – 5:37)

- The Final Reckoning (SD – 2:29)

- Original Ending (SD – 1:42)

- The Fear of God: 25 Years of The Exorcist (SD – 77:09)

- Theatrical Trailers:

- Nobody Expected It (SD – 1:44)

- Beyond Comprehension (SD – :30)

- Flash Image (SD – 1:40)

- TV Spots:

- Beyond Comprehension (SD – :34)

- You Too Can See The Exorcist (SD – :32)

- Between Science & Superstition (SD – 1:02)

- The Movie You’ve Been Waiting For (SD – 1:02)

DISC FIVE: EXTRAS (BD)

- Beyond Comprehension: William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist (HD – 27:49)

- Talk of the Devil (HD – 19:50)

Given the fact that the extras overlap between the UHDs and the Blu-rays, it’s best to address all of them en masse, starting with the various commentary tracks. William Friedkin’s commentary on what’s now referred to as the director’s cut was originally recorded for the 2000 The Version You’ve Never Seen DVD. Of course, Friedkin did revise that version yet again for the 2010 Blu-ray release, but those changes were small visual ones that didn’t affect the running time, so the older commentary still lines up. The Friedkin and William Peter Blatty commentaries on the theatrical cut were recorded for the 25th Anniversary LaserDisc and DVD releases of The Exorcist in 1998.

If you’ve ever listened to any Friedkin commentary tracks, you’ll know exactly what to expect from both of his. He was prone to narrating what was happening on screen, and often at great length. In between, he drops the occasional interesting tidbits of practical information and thoughts about the themes of The Exorcist, but those moments tend to be drowned out by the fact that seemed to think that he was performing a descriptive audio track instead of recording an actual commentary. Whether or not it’s worth wading through the endless stream of narration to dig up the valuable nuggets is up to you. (Of the two, his original commentary on the theatrical cut has less narration, so that’s probably your best bet if you only have time for one.) Blatty doesn’t narrate for his commentary on the theatrical cut, but that’s because it’s not a commentary at all, but rather an audio essay that runs less than an hour. Starting at the 57:32 mark, there are a variety of original audio excerpts, including a comparison of Linda Blair’s on-set dialogue to the overdubs by Mercedes McCambridge, plus a variety of other McCambridge demonic sounds.

The Director’s Cut Blu-ray offers a variety of trailers and TV spots as well as three different featurettes that were added for the 2010 Blu-ray release of The Exorcist: Raising Hell: Filming The Exorcist, The Exorcist Locations: Georgetown Then and Now, and Faces of Evil: The Different Versions of The Exorcist. All of them were produced by Laurent Bouzereau. The Locations featurette has already dated a bit, but it does include interview footage with Blatty, Friedkin, Owen Roizman, and Linda Blair. Faces of Evil has Friedkin, Blatty, and Roizman discussing the differences between the versions, including plenty of self-justification from Friedkin. (It does also include raw outtakes of footage that he couldn’t add back in because the negatives were lost.) However, the real treat is Raising Hell, which is a fantastic documentary on the making of The Exorcist. That’s because it offers a wealth of behind-the-scenes footage from an era where it was much less common to have a secondary crew on set in order to film it. And the fact that it’s here is thanks to Roizman, who wasn’t happy with the studio PR crew, so he gave a camera to one of his friends instead. There’s some amazing footage of the makeup, the on-set special effects, and Roizman’s inventive camera rigs, too. (Garrett Brown’s Steadicam was still a few years away, so he had to think outside of the box to film the tracking shot up the stairs). Raising Hell does include interviews with Friedkin, Blatty, Roizman, and Blair, but interviews are a dime a dozen. This behind-the-scenes footage is priceless.

The Theatrical Cut Blu-ray offers more trailers and TV spots, plus some more miscellaneous featurettes and a full documentary. Some of these were added for the 2010 Blu-ray, while others date back to the 1998 DVD. There’s the raw footage from the Original Ending that was incorporated into the director’s cut; some Sketches & Storyboards; the 1998 Introduction by Freidkin; and some miscellaneous Interviews with Friedkin and Blatty that aren’t particularly interesting. Once again, the centerpiece is a documentary, in this case The Fear of God: 25 Years of The Exorcist. Written and hosted by Mark Kermode, it’s a broader look at the background, release, and legacy of The Exorcist. It looks back at the supposedly true incident that inspired Blatty to write the book and as his journey to bring it to the screen with William Friedkin. From there, it covers plenty of stories about the production—and it doesn’t shy away from Friedkin’s problematic behavior on set and off—before moving on to the challenging post-production period and the film’s release (including censorship issues). The Fear of God features plenty of Roizman’s behind-the-scenes footage and Dick Smith’s makeup tests, as well as interviews with Friedkin, Blatty, Smith, Linda Blair, Ellen Burstyn, Max Von Sydow, Father William O’Malley, Father Thomas Bermingham, and many more. It’s a fantastic overview of the history and legacy of The Exorcist, and it’s probably the best place to start with all the extras.

Finally, the bonus Blu-ray adds two more featurettes that were added for the 40th Anniversary Edition Blu-ray: Beyond Comprehension: William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist and Talk of the Devil. Beyond Comprehension is really all things William Peter Blatty: it offers a tour of the cabin where he wrote the book; his thoughts about researching and writing it, including revising it for the 40th anniversary; and a tour of some of the Georgetown locations for the story. It also includes Blatty reading excerpts from the book. Talk of the Devil focuses on the supposed real-life exorcism that inspired Blatty. It’s footage of interviews with Father Eugene Gallagher that were conducted by Mike Siegel shortly after the release of the film.

That’s pretty much all of the previously available extras for The Exorcist, minus some text-based pages that were included on the various DVD releases and haven’t been carried forward ever since. Essentially, this is the 40th Anniversary Edition with the addition of the two new UHDs. So why hasn’t Warner Bros. released this version in North America? Well, because it’s David Zaslav-era Warner Bros. right now. This Region-Free Ultimate Collector’s Edition Steelbook set is still the one to own if you’re a fan of The Exorcist, and while it can be expensive, it’s pretty comprehensive. It’s available from Amazon U.S. and a variety of other sites as well, and you can find a better price with some diligent hunting (I picked it up from Orbit DVD for $50, but they don’t appear to have it anymore). It’s worth the effort.

- Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter, Facebook, and Letterboxd).