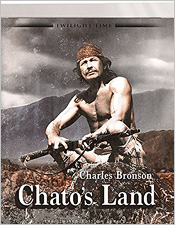

Chato's Land (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Michael WinnerRelease Date(s)

1972 (April 12, 2016)Studio(s)

Scimitar Films/United Artists (Twilight Time)- Film/Program Grade: B+

- Video Grade: B

- Audio Grade: B

- Extras Grade: B+

Review

Charles Bronson had already been kicking around the American film industry for twenty years when he teamed up with British director Michael Winner in 1972 for Chato’s Land, but it wasn’t until this successful if unusual collaboration that he found the director who would catapult him to superstardom. Bronson had already found success in films like The Dirty Dozen and The Great Escape, of course, and Sergio Leone had put his features to iconic use in his 1968 masterpiece Once Upon a Time in the West. The stone-faced messenger of vengeance that would become Bronson’s trademark character, however, was honed to brutal perfection by Winner; Chato’s Land was the rough draft, but two years later the director and Bronson would perfect the archetype in Death Wish – and Bronson would run the character into the ground up until the late 1990s. For some reason Chato’s Land remains rather obscure among Winner-Bronson collaborations – compared to The Mechanic and the three Death Wish films they did together, it’s relatively unknown. Yet it’s an efficient, beautifully cast little Western – if one in which Winner’s more unseemly qualities as a director are on fully unpleasant display.

The spare storyline is perfect for Winner’s sense of brute force: Chato, a “half-breed” Apache (Bronson) is forced to shoot a racist sheriff in self-defense. Even though it’s justifiable homicide, the local white men freak out and assemble a motley posse to go after Chato. Led by a Confederate war veteran (Jack Palance), the posse consists mostly of men who are incompetent at best and profoundly evil at worst – there are more than enough murderers and rapists to go around, making the alleged “killer” Chato the most sympathetic figure in the movie. The film essentially consists of one long chase, in which the posse pursues Chato in what they think will be a simple mission, only to find themselves picked off one by one as they travel deeper into the Western landscape that he calls home. The slim plot is primarily a pretext for a lot of tough dialogue and boorish behavior, most of which is riveting thanks to the astonishing cast Winner assembled; the posse is filled with reliable character actors like Richard Jordan, Richard Basehart, James Whitmore, and – playing shockingly against type – Ralph Waite and Victor French. The cat and mouse game between Bronson and these men is terse and powerful.

It’s also brutal to the point of excess, a problem common to Winner’s “entertainments.” I’ve often found Winner to be a fascinating figure: on the one hand, he’s an erudite, refined Englishman who turned to writing a gourmet food column when he retired from directing. On the other, his movies can almost all be characterized as odes to sadism, and he never met a rape scene he didn’t like – violence against women is as much an auteurist stamp in his films as split screens are in De Palma’s or Steadicam shots are in Scorsese’s. The violence is generally justified in his films given the subject matter, but his lingering on it often feels a bridge too far – after a certain point it's unclear if we’re supposed to be revolted by the characters’ thuggish behavior or reveling in it. Of course, this ambiguity is, while problematic at times, also what gives Winner’s work its force, and Chato’s Land is nothing if not forceful, a fine example of the cycle of 1970s Westerns that feel deeply connected to their cultural moment of Vietnam and Nixon.

In fact, the political and allegorical implications of the material, which clearly evokes Vietnam in its story of poorly prepared white men heading into an environment they don’t understand and having the tables turned on them by natives, are nicely explored by screenwriter Gerald Wilson in an interview featured on Twilight Time’s Blu-ray of Chato’s Land. Wilson spends nearly twenty minutes explicating these ideas and discussing the film’s making in an insightful conversation that, taken together with Julie Kirgo’s excellent liner notes, provides a nice overview of the movie’s production and significance. The transfer is solid but far from perfect due to numerous flaws in the source material – this is not a film that has been shown the proper respect by its corporate stewards. Nevertheless, the Blu-ray marks a vast improvement over any previous editions of the movie that I’ve come across, and is well worth picking up for Bronson and Western enthusiasts.

- Jim Hemphill