The film turned out to be one of the most popular movies of 1968 and, with an assist that same year from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, helped to mainstream the often marginalized science fiction genre. (And contrary to claims in some film history books, Planet of the Apes and 2001 did not get released on the same date. Sigh…)

Anyway, for the occasion, The Bits features a Q&A with a trio of film historians, who discuss the film’s virtues, influence, and modern-day relevance.

The participants are (in alphabetical order)….

Jeff Bond is the author (with Joe Fordham) of Planet of the Apes: The Evolution of the Legend (Titan, 2014). His other books include The World of the Orville (Titan, 2018), The Art of Star Trek: The Kelvin Timeline (Titan, 2017), Danse Macabre: 25 Years of Danny Elfman and Tim Burton (included in The Danny Elfman & Tim Burton 25th Anniversary Music Box, Warner Bros., 2011) and The Music of Star Trek (Lone Eagle, 1999). Jeff is the editor of Geek magazine, covered film music for The Hollywood Reporter for ten years, and has contributed liner notes to numerous CD soundtrack releases.

John Cork wrote and directed the documentary short Taking the Shot: The Films of 20th Century Fox (2010). He is the author (with Collin Stutz) of James Bond Encyclopedia (DK, 2007) and (with Bruce Scivally) James Bond: The Legacy (Abrams, 2002) and (with Maryam d’Abo) Bond Girls Are Forever: The Women of James Bond (Abrams, 2003). He is the president of Cloverland, a multi-media production company. Cork also wrote the screenplay to The Long Walk Home(1990), starring Whoopi Goldberg and Sissy Spacek. He has recently contributed introductions to new hardback editions of three of the original Ian Fleming James Bond novels: Casino Royale, Live and Let Die, and Goldfinger.

Lee Pfeiffer is the co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of Cinema Retro magazine, which celebrates films of the 1960s and 1970s and is “the Essential Guide to Cult and Classic Movies.” He is the author of several books including (with Dave Worrall) 40-Year Evolution: Planet of the Apes (included in the 2008 40th anniversary Blu-ray release) and The Essential Bond: The Authorized Guide to the World of 007 (Boxtree, 1998/Harper Collins, 1999) and (with Philip Lisa) The Incredible World of 007: An Authorized Celebration of James Bond (Citadel, 1992).

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): How do you think Planet of the Apes should be remembered on its 50th anniversary?

Jeff Bond: It’s still basically an iconic brand given the three recent movies. And when you look back at 1968, Planet of the Apes and 2001: A Space Odyssey were really the first American science fiction “A” movies — movies that were artistic successes, big budget, major productions that were about ideas. And Planet of the Apes created the first high-profile science fiction movie franchise that lay the groundwork for Star Wars and many other movies.

John Cork: Planet of the Apes is one of the most significant science fiction films ever made. It should be remembered as a high-water mark of American studio films of the era. It played during the spring of 1968, and in part because of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in early April, the dark satire and the underlying counter-culture message resonated forcefully with audiences. It also played in theaters simultaneously in some markets with 2001: A Space Odyssey, a much more hopeful and amorphous film, marking the year of their release as a zenith for science fiction in cinema. And, quite simply, it should be remembered for one of the greatest movie endings in the history of cinema.

Lee Pfeiffer: It’s hard to overstate the influence of Planet of the Apes on the sci-fi film genre. Until then, sci-fi didn’t get much respect, but the one-two punch of that film followed by Kubrick’s mind-blowing 2001 would cause critics and audiences to reevaluate the genre as something more than hapless earthlings trying to repel creatures with ray guns. There had been some “intelligent” sci-fi films prior to this, of course, but even the best often had hokey elements to them. The original version of The Thing and Forbidden Planet are generally cited as milestone films in the genre, and given the time period in which they were made, they were indeed major leaps forward in terms of gaining respectability for sci-fi movies. However, as beloved as these films are, certain elements creak with age and have not withstood the test of time the way the original Planet of the Apes has. There is nothing dated about it at all. It retains all of its emotional power and the social messaging seems as timely now as it did in 1968, which is actually a sad commentary on the world today.

Coate: Do you remember when you first saw the movie?

Bond: I saw it on television when I was in 5th or 6th grade and it was a big event, and I quickly caught up on all the films as they aired on television — I finally saw the original movie in a theater in college. As a kid, I think we were just crazy for the idea of gorillas riding on horseback shooting rifles. It was just a bizarre, amazing world with these talking, unforgettable simian characters. As I got older I became more and more entertained by the politics and ideas behind it.

Cork: I saw it in 1968. I believe it was in the summer because my Aunt Lois took me to see the film at a local drive-in. I was six years old. I was immediately captivated. We stopped by a convenience store on the way home and she got me a pack of the bubble-gum cards. My friend Grayson and I immediately began collecting them. The basic story was so simple, so clear that we could understand it, and understand the meaning of the ending. There are lots of films that one loves when one is six, but that don’t hold up years later. Planet of the Apes holds up brilliantly.

Pfeiffer: I saw it at age 11 with my father when it first opened at the Stanley Theatre movie palace in Jersey City, New Jersey. I think that the very concept made everyone skeptical that the premise of the movie would be anything other than ridiculous, though the advance TV spots did look intriguing. I primarily wanted to go because I was a major Charlton Heston fan. In those days, there wasn’t much major “buzz” on forthcoming films unless they were the subject of scandalous news stories like Cleopatra (Burton and Taylor plus a ballooning budget), Mutiny on the Bounty (Brando taking the hit for the film’s skyrocketing costs) and The Alamo (a murder on the set and political concerns about the script). Today, the word is out on most movies for better or worse before it even wraps. But in 1968, Planet of the Apes was a mystery to the average movie-goer. The enthusiasm that greeted the film in those first few days spread rapidly, bolstered by the kind of great reviews sci-fi movies rarely enjoyed. It suddenly became a “must-see” phenomenon.

Coate: In what way is Planet of the Apes a significant film?

Coate: In what way is Planet of the Apes a significant film?

Bond: It was groundbreaking in its makeup effects — this was the first time what was essentially an entire alien, inhuman race of creatures had been created and put on film before and an entire civilization had been imagined, designed and made convincing on film. It was an idea that was immediately classic — you had distinctive, excellent actors bringing these simian characters to life and making them immediately memorable, and you had Charlton Heston as this iconic stand-in for all the best and worst in humanity, and one of the great shock endings in movie history. Plus a brilliant score by Jerry Goldsmith that is still one of the greatest, most experimental achievements in movie music.

Cork: Planet of the Apes works so well because of its brilliant use of irony, its pointed exposure of hypocrisy, its willingness to play every joke and absurdity completely straight. Few films can work both as straight science fiction and as mocking social satire. Planet of the Apes does both very well. It is without equal in this. It is a film that speaks to so much: the battle between science and religion, the racial unrest in America, the hubris of man.

The original film has these absolutely absurd problems with its premise. A bit of a spoiler here, but what astronaut would think that some random planet would have a breathable atmosphere, water, temperate climate, humans, Earth flora, horses, apes, and the exact same spoken and written language? The key moment comes when Taylor is wounded and captured. He looks over and sees gorilla hunters standing, smiling for a photo with dead human bodies at their feet. The camera is vintage 1800s technology. Period photos like this can be found with white men posing with the bodies of any number of indigenous peoples, or with escaped slaves, or lynching images. But this particular image had even more recent precedents: the shocking images of the French troops posing with the bodies of dead Algerians a decade earlier. That moment is the moment when you first hear the apes speak English, and it is so filled with meaning that most viewers instinctively understand that this film has something to say. And it is also significant that the first word an ape speaks is, “smile.”

This is a film that tells viewers that we are going to see our world reflected back at us through this thin premise of a planet ruled by apes, but the way the film reflects our world back is always chilling, always surprising, always thought-provoking.

Pfeiffer: The sheer intelligence of the screenplay by Michael Wilson and Rod Serling set it apart from most sci-fi movies. They had the benefit of working from an inspiring source novel by Pierre Boulle, who had written the book that The Bridge on the River Kwai had been based on. The screenplay provided old-fashioned cliffhanger thrills with wry social commentary, often in a humorous way. The film was released in 1968 amid the most contentious events America had experienced since the Civil War. The civil rights movement was in high gear, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated within a few months of each other. President Johnson, beleaguered by the growing anti-Vietnam War protests announced to a shocked nation he would not run for a second term. The Democratic Party had devolved into pure chaos and resulted in the nationally televised riots that defined their convention in Chicago that summer and allowed Richard Nixon to rise from the political graveyard and gain the presidency. We all know how that would end. Planet of the Apes was a finished film before any of these events occurred yet it seemed positively prescient by the time it opened. Suddenly a movie depicted white males as an oppressed minority, powerless to stop social injustice by rulers who had on blinders. There were also pleas to humanity about the insanity of nuclear war. It was pretty heavy stuff to contend with, but it spoke poignantly to people during that fateful year.

Aside from its social significance, Planet of the Apes was simply great filmmaking. The makeup by John Chambers was so incredibly good that he was awarded a special Oscar because the makeup category wasn’t in existence at the time. Chambers revolutionized the industry through his amazing achievement, even though it did cause one “casualty”: Edward G. Robinson had originally been cast as Dr. Zaius, but he had a severe reaction the makeup and had to drop out. He was replaced, of course, by the equally impressive Maurice Evans who gave the screen performance of his life. (Heston and Robinson would ironically work together a few years later on another cautionary futuristic tale, Soylent Green, which was Robinson’s final film.) I can’t fail to mention the innovative musical score by Jerry Goldsmith, who was simply a contract composer at the time, assigned by Fox to whatever film they instructed him to work on. He was a real asset to the studio during these years and his offbeat, chilling score for Planet of the Apes earned him an Oscar nomination.

Coate: In what way was Franklin Schaffner an ideal choice to direct Planet of the Apes, and where does the film rank among his body of work?

Bond: I think Patton and Planet of the Apes are Schaffner’s best films — in fact, I think Pauline Kael said she thought Planet of the Apes was a better-directed film than Patton, which won the Best Picture and Best Director Oscar. Schaffner was a very intelligent director and he was at home dealing with politics and ideas — he’d made a great political thriller, The Best Man, before Planet of the Apes.

Cork: Schaffner is a tremendously under-rated director. All of his films have merit, but Planet of the Apes, Patton, Nicholas and Alexandra, Papillon, Islands in the Stream, and The Boys from Brazil are all great films. I rank Planet of the Apes and Patton as his two greatest films. I was fortunate enough to meet him once. As a student at USC, my friend Jeff Burr let me know that Schaffner was going to talk to a class he was taking after a screening of Islands in the Stream. It was a small group, and Schaffner humored all our questions. He struck me as a humble man, but he really was fascinated by the role of the individual in the sweep of history.

I think he was greatly affected by his own life, having been born to missionaries in Japan, seeing the rise of a brutal form of imperialism there, fighting in World War II, and seeing the Cold War, the push-back against Civil Rights and McCarthyism rise up here. He never directed for The Twilight Zone, but he worked on many Rod Serling projects in the mid-50s. He was deeply affected by the death of JFK, whom he really saw as a beacon of hope for the nation.

He was the perfect director for Planet of the Apes because he didn’t make many films about heroes and villains. He made films about people. He knew how to make us root for Taylor, but see how his arrogance (and our own) will need to be thrown back in his face.

But it is important to cite three other vital contributors to Planet of the Apes. The first is Pierre Boulle who wrote the novel, and wrote the novel The Bridge over the River Kwai that was adapted into David Lean’s classic film. His premise and vision cannot be undervalued. The second is Rod Serling. Planet of the Apes in many ways is the ultimate Twilight Zone episode. Serling penned the ending of the film, which is reminiscent of many classic Twilight Zone episodes. Finally, there is Michael Wilson, a brilliant, formerly blacklisted writer who did the final rewrites on the script. A lot of the indignation that lies just below the surface of the film can be credited to him.

Pfeiffer: Blake Edwards had supposedly been considered to be the director. Can you imagine? Fortunately, the producer, Arthur P. Jacobs listened to Charlton Heston, who had made a good film called The War Lord with Schaffner a few years before. He was brought on board as director and proved to be the perfect choice. Schaffner knew how to find the perfect balance between suspense and humor, without ever overdoing the latter. It would have been so easy for the film to have slid into satire just to get a few cheap laughs but Schaffner’s direction avoided this. The movie certainly ranks with Patton as his greatest film achievements, though they are pointless to compare for obvious reasons. Let’s just say that they demonstrate the diverse body of work Schaffner was capable of excelling in. He was underrated. I think his career was hurt by the expense failure of Nicholas and Alexandra. He did manage to make the occasional high profile hit such as Papillon and The Boys from Brazil. And Islands in the Stream is a wonderful film, but for the most part, he never got the high profile projects he deserved.

Coate: How do the 1970s sequels and the recent remakes and reboots compare to the original movie?

Coate: How do the 1970s sequels and the recent remakes and reboots compare to the original movie?

Bond: The first three sequels I think all have their strengths. Beneath the Planet of the Apes is just a fun adventure with the crazy twist of the bomb-worshipping mutants. Escape from the Planet of the Apes is really amazing because it is a fish out of water comedy that ends with murder and infanticide, and it’s a tonal shift that is inevitable as we see the character played by Eric Braeden realize very quickly that Zira and Cornelius, these lovable chimpanzee characters, are really an existential threat to human civilization, and he’s absolutely right. He takes on one of the most shocking acts of villainy you’ll ever see in a movie, but given the circumstances, from his perspective he’s completely right and completely justified. And then Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, with its allegory to the Watts Riots, is one of the most politically daring science fiction movies ever made. After that, Battle for the Planet of the Apes and the Tim Burton movie from 2001 are really much less ambitious adventures, and the three reboots are very clever, groundbreaking technical achievements that function by making you really believe in the simians as flesh and blood characters — it’s a more subtle approach that doesn’t wear its politics on its sleeve quite so much but still says a lot about empathy and humanity’s responsibility for the world we live in.

Cork: I love Paul Dehn who wrote on many of the 1970s sequels, but they are pale shadows compared to the original. Beneath the Planet of the Apes borders on dreadful, although it is worth seeing for the last few minutes, which borrows (or steals) from Bridge on the River Kwai, Dr. Strangelove and the 1967 Casino Royale! The addition of Paul Frees, the voice of The Haunted Mansion, brings something less than the appropriate solemnity to the situation.

Escape from the Planet of the Apes is quite delightful until the ending. If you want to make a small child cry, show them Escape. Sure, we’re all happy Caesar lives, but things do not end well. The Shape of Water owes much to this film.

Conquest of the Planet of the Apes feels like a TV movie, and its retcon sequel, Battle for the Planet of the Apes should be avoided at all costs.

I loved the TV series when it came out and watched numerous episodes of the animated series, but I haven’t seen them since.

Tim Burton’s remake falls flat for me with the middle becoming particularly muddled. There is something very wrong about unironically putting Mark Wahlberg, a man convicted of attempted murder for a racist attack, in the Planet of the Apes universe.

The current series…hmmm. I liked the first one. Watching CGI gorillas magically get on horses without crushing them got old fast. Someone simply ran out of ideas for War for the Planet of the Apes. I have seen The Great Escape, Stalag 17 and The Ten Commandments. They are all better films. All would have been forgiven if the snow soldiers at the end had pulled off their masks to reveal that they were also apes. Somewhere, they lost the thread of what made Planet of the Apes so great. For me, I want to go back to sharing those Planet of the Apes comic books at summer camp, looking at those bubble gum cards, sitting at the drive-in with my aunt and feeling that sense of wonder that only the first film brings.

Pfeiffer: No one thought there could be a sequel to Planet of the Apes and Charlton Heston refused to be part of it. But Fox was in deep financial trouble at the time and studio boss Richard Zanuck imposed upon him to make Beneath the Planet of the Apes. Heston grudgingly did so because he felt obligated to Zanuck for championing the first movie when other studios turned it down. Heston agreed to give Fox one week of his time and no more. His appearances are vital to the first sequel, even though they cast James Franciscus as a Heston-look-a-like. By the way, Heston always maintained that he never saw Beneath but insisted that the world be destroyed in it so there could be no further sequels. Little did he realize that Hollywood screenwriters can accomplish anything when profits are at stake. The film was a major hit but the following sequels, though clever and good in their ways, were a case of diminishing returns. By the time Battle of the Planet of the Apes was released, the budgets had been cut to TV movie levels and the series would end until the reboots decades later. The newer films benefit from being able to stand on their own for a younger generation without being compared to the originals. They also benefit from today’s technology which has helped launch a rebooted series that has been quite successful.

Coate: What is the legacy of Planet of the Apes?

Bond: I think this is very simple as far as what the 1968 movie was trying to say. In that movie you have a religious majority suppressing ideas, suppressing science and exercising rampant, violent racism against another intelligent species. Now look at the situation we’re in today where we have a President openly dismissing science, stripping scientific information off of government websites and stripping funding from programs to advance scientific research and technology that might help us keep this planet habitable for billions of people. We literally have a movement that is declaring that the Earth is flat. All of that would have likely been laughed at if presented in 1968 during the space race when American policy was all about advancing science, technology and knowledge. Add to that the movements of nationalism and racism that are completely out front today. So the original Planet of the Apes I think is actually even more relevant now than it was in 1968.

Cork: I wish I could say that it was a film that unleashed a great torrent of brilliant Swiftian satire, or that its release did what Sammy Davis Jr. hoped it would do — make a real impact on race relations in America. This is the film that made Franklin J. Schaffner one of the hottest directors in Hollywood. It became a justification for studios to greenlight a handful of mediocre, dark, fatalistic science fiction films for a few years. Charlton Heston, who in Apes is basically playing the same arrogant character that he played in The Naked Jungle in 1954, plays the same type again in The Omega Man, three years later, once again living in a world turned upside down. I think the real legacy is very similar to The Twilight Zone. Both inspired millions of viewers to think about the world a little differently. For those who didn’t feel challenged to think, the film is still great entertainment. For those the film touched, they became a bit more aware of the hypocrisy, ignorance, hubris, and irony that so defines our world.

Pfeiffer: It’s a landmark in the science fiction film genre that paved the way for so many other intelligent, highly compelling sci-fi films. It’s impossible to know how many filmmakers it influenced and still continues to influence. I should also mention that Charlton Heston’s son, Fraser, himself a talented director, once asked me what I thought his father’s best performance was. I think he was surprised when I said Planet of the Apes. It took a great deal of skill for Heston to dominate a film populated by other actors in ape masks and he did so magnificently. He’s also a bit of a bastard, not very likable at all, which went against the astronaut-as-hero scenario. I think that’s also part of the film’s legacy in that it afforded a Hollywood legend one of his greatest roles.

Coate: Thank you — Jeff, John, and Lee — for sharing your thoughts about Planet of the Apes on the occasion of its 50th anniversary.

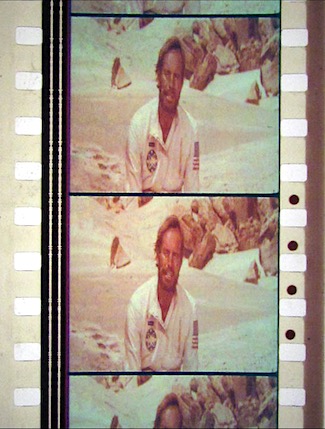

IMAGES

Selected images copyright/courtesy APJAC Productions, 20th Century-Fox Film Corporation, 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment.

SPECIAL THANKS

John Hazelton

- Michael Coate

Michael Coate can be reached via e-mail through this link. (You can also follow Michael on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook)