The participants for this segment are (in alphabetical order)…

Thomas A. Christie is the author of The James Bond Movies of the 1980s (Crescent Moon, 2013). He has written numerous other books, among them A Righteously Awesome Eighties Christmas (Extremis, 2016), Mel Brooks: Genius and Loving It! (Crescent Moon, 2015), Ferris Bueller’s Day Off: Pocket Movie Guide (Crescent Moon, 2010), John Hughes and Eighties Cinema: Teenage Hopes and American Dreams (Crescent Moon, 2009), and The Cinema of Richard Linklater (Crescent Moon, 2008). He is a member of The Royal Society of Literature, The Society of Authors and The Federation of Writers Scotland.

John Cork is the author (with Collin Stutz) of James Bond Encyclopedia (DK, 2007) and (with Bruce Scivally) James Bond: The Legacy (Abrams, 2002) and (with Maryam d’Abo) Bond Girls Are Forever: The Women of James Bond (Abrams, 2003). He is the president of Cloverland, a multi-media production company. Cork also wrote the screenplay to The Long Walk Home (1990), starring Whoopi Goldberg and Sissy Spacek. He wrote and directed the feature documentary You Belong to Me: Sex, Race and Murder on the Suwannee River for producers Jude Hagin and Hillary Saltzman (daughter of original Bond producer, Harry Saltzman). He contributed new introductions for the original Bond novels Casino Royale, Live and Let Die, and Goldfinger for new editions published in the U.K. by Vintage Classics in 2017.

Lee Pfeiffer is the author (with Dave Worrall) of The Essential Bond: The Authorized Guide to the World of 007 (Boxtree, 1998/Harper Collins, 1999) and (with Philip Lisa) The Incredible World of 007: An Authorized Celebration of James Bond (Citadel, 1992) and The Films of Sean Connery (Citadel, 2001). Lee was a producer on the Goldfinger and Thunderball Special Edition LaserDisc sets and is the co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of Cinema Retro magazine, which celebrates films of the 1960s and 1970s and is “the Essential Guide to Cult and Classic Movies.”

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

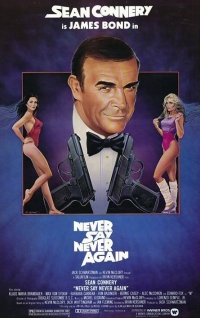

And now that the participants have been introduced, might I suggest preparing a martini (shaken, not stirred, of course) and cueing up the soundtrack album to Never Say Never Again, and then enjoy the conversation with these James Bond authorities.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): In what way is Never Say Never Again worthy of celebration on its 35th anniversary?

Thomas A. Christie: Never Say Never Again is one of the great curios of James Bond on film. Independent of the main Eon Productions series, it brought Sean Connery back to a role that few (if any) imagined he would ever assume again, and brought the story of Thunderball – and the SPECTRE organization – right up to date for the technologically-focused world of the 1980s. This Warner Bros. release was a gift to entertainment journalists at the time, who eagerly commentated on a “Battle of the Bonds” between Connery’s belated return and Roger Moore’s sixth appearance in the role, Octopussy, which debuted in the same year. (In reality, of course, several months divided the premiere screenings of each film, making it less of a head-to-head skirmish than had perhaps seemed likely.) Worlds apart from 1967’s deeply divisive comedic ensemble caper Casino Royale, this slick Irvin Kershner-helmed feature answered a question that many a critic had previously asked, namely what a James Bond movie might look like if it was produced by a creative team other than the one that had been responsible for the series’ meteoric success ever since 1962’s Dr. No.

John Cork: Celebration? It is a stark warning, a cinematic signpost marking danger, a brutal example that cross-breeding nostalgia with greed never results in a beautiful baby. It is an unabashedly terrible film. Yet, it is fascinating. It is the answer to every fan who thinks, “If only I were running the show.” It is the film that CBS should have watched before they brought back Burke’s Law thirty years after it went off the air, the movie Kathleen Kennedy should have watched before greenlighting Solo: A Star Wars Story, the movie that made me realize that we never needed a Beatles reunion. This is a 1983 film with the director of the highest-grossing film of 1980, the cinematographer of the highest-grossing film of 1981, and Sean Connery starring as James Bond. What could go wrong? This is not to say that the film is without any charms, that certain scenes and performances don’t work, that fans who love the movie are somehow “misguided.” I love talking to those who are passionate about films that fall flat. The script isn’t terrible, but Irvin Kershner was absolutely not the right director for the film. He had once been pressured to work for the CIA but had resisted. He didn’t like spies or spy films, his only previous experience in the genre being the messy 1974 parody, S*P*Y*S. He and Connery got on well and were friends (they had worked together years earlier on A Fine Madness), but the film needed a visionary director who wanted to make the best Bond film ever, not one that looked down on the genre and the character. For years, Kevin McClory had tried to exploit the rights to Thunderball, which he had obtained in a legal settlement with Ian Fleming’s oldest friend, Ivar Bryce, back in 1963. For years, fans who objected to the “silliness” of the Roger Moore Bond films cheered him on. When, after years of legal wrangling this movie came to pass, the Bond fan community could barely contain their glee. But as Ian Fleming wrote in You Only Live Twice, “It is better to travel hopefully… than to arrive.”

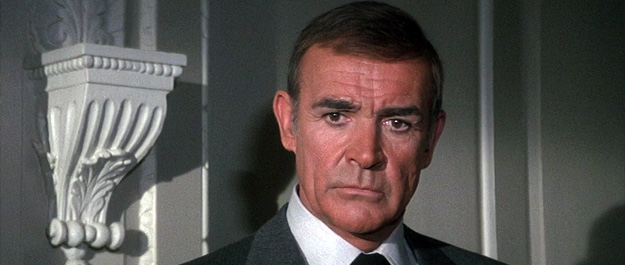

Lee Pfeiffer: The film is significant primarily because it marked the final screen appearance of Sean Connery as 007. Bond fans seem to have mixed emotions about the film with most considering it as having fallen short of its potential. Nevertheless, it did close the books on the Connery era of Bond and for that reason alone it has significance in movie history.

Coate: Can you describe what it was like seeing Never Say Never Again for the first time?

Christie: I watched Never Say Never Again in the eighties, and was immediately struck by the film’s strange mélange of modernity and traditionalism. Given that it was unfettered by the cast and conventions of the Eon series, it’s strange to see just how conservative the divergence often actually is between the official Bond movies and this independently-produced feature. Many of the familiar tropes are all in place, albeit that the regular supporting characters are recast with different faces such as Edward Fox as “M” and Pamela Salem as Miss Moneypenny, all fulfilling similar or near-identical functions to their counterparts in the Eon films. Yet others, such as replacing Desmond Llewelyn’s avuncular, eccentric “Q” with Alec McCowen’s curmudgeonly, resource-strapped quartermaster Algy, seem like strikingly effective creative choices which offset the jarring absence of long-established elements such as Maurice Binder’s gunbarrel logo or the legendary Monty Norman theme music. Perhaps most intriguing of all is seeing Bond as a character in middle age (Connery was 52 at the time of filming), now forced to rely more on his wits than his physical prowess to achieve his aims – a dash of realism that seemed a world away from the wisecracking excesses familiar from some points of the Roger Moore era.

Cork: For a few short hours, I thought I had the greatest story for seeing Never Say Never Again for the first time. I had, with a friend, snuck into a screening at the Academy Theater in Beverly Hills by giving the list-checker a name that I had spied on his list a few moments earlier. But the next day, I ran into [collaborator and frequent contributor to this series] Bruce Scivally. We were both students at USC and both Bond fans. I dropped that I had seen the film. Bruce had, too. Then he told me his story. He knew a fellow student who had gone to school with Sean Connery’s son, Jason, and that student invited Bruce and some others to attend that same Academy theater screening. Well, their names were not on the list. A demand was made for a telephone, a number was called and some poor publicist from Warner Bros. was soon standing at attention saying things like, “Yes, sir, Mr. Connery. Right away, Mr. Connery. So sorry, Mr. Connery!” So, Bruce got to see the film for the first time because Sean Connery demanded he be let into the theater.

Seeing the film was a strange experience. Although I was a college student, I had worked my way into two premieres and a critics’ screening for Octopussy. Since I had, well, lied my way into this screening, my friend and I were hiding in the darkest corner of the theater sitting next to the wall. Fortunately, there wasn’t a bad seat in that theater. When the film started with that atrocious soft jazz title song, it became clear that something was off. This looked more like a film from The Cannon Group than a slick Bond film. I remember thinking, “How could the cinematographer of Raiders of the Lost Ark make a film look so bad?” But I was a hardcore Bond fan, so I looked for things to love. I found a few. It took a while for it to sink in to me just how disappointing the film was.

Pfeiffer: I saw it at an advanced critics’ screening in New York City. Anticipation was through the roof if you were a Bond fan. Connery had already quit the series in 1967 only to come back in 1971 with Diamonds Are Forever. While that film was a major hit, most fans were disappointed by the flabby script and overt emphasis on sometimes over-the-top humor. So they felt they had another bite at the apple with Never. There was also the sense that the film couldn’t disappoint because it was a remake of Thunderball. Without going over well-trod territory, producer Kevin McClory had been involved in a lawsuit in the early 1960s over the rights to the novel Thunderball. He was awarded the screen rights and served as one of the producers on the blockbuster 1965 screen version of the book which also starred Connery. When McClory tried to exercise his rights to remake the film in the mid-1970s using a screenplay co-written by himself, Len Deighton and Sean Connery (who did not intend to star at that time), Eon Productions took legal moves to block the production from going ahead. It finally did see the light of day in 1983 with Never Say Never Again because producer Jack Schwartzman succeeded where McClory couldn’t, though McClory is still listed as an executive producer. By this time, Connery had been convinced by his wife to star in the film (she also came up with the title.)

In 1983, much was made over “The Battle of the Bonds” because Eon was simultaneously filming Roger Moore’s “official” 007 film Octopussy. They were both supposed to be in theaters at the same time but Never ran into production difficulties that delayed its release until the fall. Octopussy opened in the summer. By the time fans got to see Never, anticipation was at a fever pitch, but the film didn’t live up to expectations. It didn’t have the same feel or polish as the Eon films and of course the absence of the gunbarrel opening and a pre-credits scene also felt strange. The script was rather patchy as well but for me, I suppose the excitement of seeing Connery back as Bond made me overlook flaws that became apparent on future viewings. For one, Michel Legrand’s sparse musical score is mediocre at best and the absence of dynamic music really drags the film down. There’s a bootleg version floating around in which a fan dubbed in old John Barry music over the action and it works considerably better. Additionally, the climax of the film is a genuine mess and was botched during production, causing Connery to have to return to reshoot some of the climax. It’s still a mess especially compared to the spectacular battle at the end of Thunderball. Instead, Never gives us a murkily-photographed and edited one-on-one struggle between Bond and the villain Largo that ends the film on a rather limp note. Having said all that, there is much I like about the film even if it’s better in parts than as a whole. The computer game battle royale between Bond and Largo is particularly enjoyable and some of the dialogue is quite witty. On the other hand, there’s too much satirical humor. Edward Fox’s “M” is abysmal, making him a complete idiot and Rowan Atkinson’s appearance as a bumbling agent is best forgotten.

Coate: In what way did Sean Connery’s return and final performance as Bond stand out?

Christie: Just as Never Say Never Again called for a more mature version of Bond, now middle-aged and no longer the superfit man of action he was in his 1960s glory days, so too did Connery step up to the plate with a suitably seasoned and nuanced take on the role. Though still quick on the draw with a serrated one-liner and able to routinely out-think his opponents, this was a Bond who seemed mildly like an anachronism in the high-tech digital age of the eighties while never quite appearing to be entirely out of his depth. Connery’s take on this older variation on the character is interesting. He seems considerably more comfortable with the character, offering a Bond whose usual professional efficiency is complemented by occasional mellowness and easy wit, and judging by interviews at the time he seems to have enjoyed the filming experience far more than his numerous appearances back in the golden age of the spy thriller (albeit that the production was reportedly not without its frustrations for him on occasion). Connery’s career was, of course, on the cusp of entering a long winning streak at that particular point, with roles such as Juan Sanchez Villa-Lobos Ramirez in Russell Mulcahy’s Highlander (1986), William of Baskerville in Jean-Jacques Annaud’s The Name of the Rose (1986), Professor Henry Jones Sr. in Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), and most especially his Oscar-winning performance as Jimmy Malone in Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987), all just a few years away. These movies each called for him to portray wise, paternalistic characters who can offer experience and understanding (often to younger, less practiced figures) that came with years of practical knowledge and proficiency in various particular skills. In a way, his interpretation of Bond as an astute veteran of the espionage world in Never Say Never Again would kick-start this new phase of Connery’s filmography, emphasizing the ways in which 007’s deadly physicality had given way to an approach to the intelligence world that relied more on problem-solving and outwitting enemies than being able to overpower them. For this Bond, age may have lessened his brute strength, but it brought dividends in the form of greater insight and self-knowledge.

Cork: Sean Connery is always a joy to watch, particularly as Bond. But his performance in Never Say Never Again shows the importance of a strong director with a clear vision. Too often, Connery looks like a man out of step with the modern world, one who is baffled by seemingly most everything. He too often looks confused, cautious, confounded. When Patricia (Prunella Gee) knocks on his door at Shrublands and, later, when Q surprises him with an exploding pen, he seems genuinely startled and worried, unlike the unflappable Bond he used to play. He can’t even peak through a window properly without setting off the roll-up blinds. After seeing clearly suspicious behavior and surviving an assassination attempt, he fails to properly investigate and report what happened, thus allowing the world to be held hostage to nuclear terrorists. When he talks, he too often sounds like a bemused old uncle who grumbles about how in his day you had to get up and walk over to the TV to change the channel. And then we must endure the spectacle of James Bond wearing overalls in the film (an homage to his sibling Neil’s overalls in Operation Kid Brother?) and later biking through town in his boxer shorts looking all too pleased with himself, which still galls me to this day.

Pfeiffer: I think it’s one of Connery’s best performances as Bond. His wry wit is ever-present and he refreshingly plays up the aging process that Bond has to contend with. He looks terrific even if there seems to be some inconsistencies with his toupees. He also seems to be having a good time even though he was quite miffed at what he felt were unprofessional aspects of the production when filming was underway. I think Connery felt comfortable working with director Irvin Kershner, who he had collaborated with on the 1966 zany comedy A Fine Madness. The film will never be a so-called “Gilt-edged Bond,” but it is underrated in many aspects.

Coate: In what way was Klaus Maria Brandauer’s Largo (or Max von Sydow’s Blofeld) a memorable villain?

Christie: Whereas Adolfo Celi’s sixties take on Largo had been dominated by the character’s glowering disposition and barely-contained temper, Brandauer’s contemporary approach to this villain was quite different – coldly charming, distant and sadistic, when his fury does boil over it seems all the more effective because of the way it clashes with his otherwise cool external demeanor. This variation on Largo is just as brutal and dangerous as his 1965 equivalent but also more darkly calculating in his malign intentions, lending him greater depth and making him a more complex villain as a result. By comparison, von Sydow’s Blofeld seems curiously genial and paternalistic for a criminal mastermind. Though as erudite and sophisticated as ever, this Blofeld’s sense of threat is blunted by the character’s apparent amiability and almost grandfatherly quality, meaning that he appears almost as anomalous a figure as Charles Gray’s archly witty but strangely toothless version of the SPECTRE chief in 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever. Given that much of von Sydow’s screen time is reputed to have been left on the cutting room floor after the film was edited, however, we may never know if this incarnation of Blofeld may have had more in common with his cinematic forebears had the entirety of his appearance survived into the eventual theatrical cut.

Cork: “Sweet, like money!” Brandauer’s Largo is introduced inauspiciously via a distant video screen blathering exposition. His first scene where he’s not on a video monitor comes over 35 minutes in when he lands on his yacht and goes out of his way to politely tell his staff, “Good morning.” He plays Largo as if he were a frustrated romantic poet. He is far more obsessed with Domino than with his mission to extort the Western powers. When she asks Largo what would happen if she ever left him, he gets an expression on his face of someone experiencing sudden explosive diarrhea. This is not a man with the focus and control to plot global extortion. There is never any menace in his performance, his glance often wandering around like a kitten fascinated by a flashlight beam. Much of his mannerisms lead one to assume his inspiration was Jerry Lewis in The Nutty Professor. That said, one can see the villain he could have been with the comparatively brilliant performance he gives during the Domination game scene.

Things are not helped by the usually amazing Max von Sydow as Blofeld. In some of the original material that became the basis for Thunderball, it was suggested that Burl Ives (the affable snowman in the old Rankin-Bass Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer Christmas special) could play Blofeld, and Max von Sydow seems to have been informed of this and does his best Burl Ives impersonation.

Pfeiffer: Film critics Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel were quite influential in 1983 and they both thought Never was terrific. I think they cited Brandauer as the best Bond villain ever. I wouldn’t go that far but his performance is certainly very inspired. He has all the ingredients of the classic Bond villain: he’s sophisticated, witty, and charismatic. He wisely chose not to emulate Adolfo Celi who played Largo in Thunderball and whose performance is much-beloved by fans. Instead, he made the role his own and did an excellent job of it.

Coate: In what way was Kim Basinger’s Domino (or Barbara Carrera’s Fatima Blush) a memorable Bond Girl?

Christie: Kim Basinger brings a welcome sense of credulity to Domino; the character becomes more sympathetic and relatable as a result of her grief and sense of betrayal at the hands of Largo and his murderous machinations. She is capable and resourceful, yet also frequently out of her depth as a result of Largo’s constant scheming; Bond’s genuine concern for her, especially when rescuing her after Largo sells his unsuspecting lover into captivity, makes this one of the more emotionally impactful romances for 007. On the other end of the spectrum, Barbara Carrera seems to be having a lot of fun as the ruthless Fatima Blush. The character, who is an updating of Luciana Paluzzi’s Fiona Volpe in Thunderball (the Fatima Blush name being drawn from an earlier draft of the 1965 film’s script), is a lethal, sado-masochistic villain who clearly relishes her work a little too much, and Carrera shares a playful on-screen chemistry with Connery’s Bond, leading to a spirited interchange between them that eventually ends in Blush’s untimely demise.

Cork: The old story is that when Kim Basinger won her Best Supporting Actress Oscar for L.A. Confidential it was because the Academy didn’t have an award for Most Improved. Never Say Never Again would be one of those movies from which she improved. She delivers her lines like a nine-year-old playing Maggie in an elementary school production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. She is a beautiful woman giving a disappointingly sexless performance, and mostly I feel pity for her watching it. She has enormous talent but needs a strong director. She is just lost in this film.

On the other hand, Barbara Carrera as Fatima Blush steals this movie. She lifts it up in almost every scene she’s in except for her brutally awkward meeting with Bond at a Nassau bar and the cringe-worthy love-making scene on the yacht. Regardless of how idiotic it is to think one might kill someone by tossing a snake from one moving car to another, Carrera does it with aplomb and a smile. The film does everything to sabotage her character, even having her go from water-skiing on a single ski to magically skiing on two skis. But her manic performance predates the similar Xenia Onatopp in GoldenEye, and it is quite fun to watch. Sadly, she dies far too early to save the movie’s final act.

Pfeiffer: Kim Basinger was a struggling actress with only a couple of modest feature film credits when she caught the eye of the late Playboy film critic Bruce Williamson, who championed her talents. I knew Bruce and remember him telling me that he felt she had the makings of a major star but needed some publicity. Bruce told Hugh Hefner about her and ultimately she appeared in a major photo feature in Playboy just around the time she was hired to play Domino in Never Say Never Again. It’s hard to fathom in the #MeToo era, but in decades past up-and-coming actresses welcomed exposure in Playboy. Hefner put her on the cover many months before the film opened and she made quite a splash. Bruce always pointed out, however, that Basinger was more than a pretty face – she could act and he hoped that the Bond film would catapult her career, which it certainly did. She gave a fine performance. Like Klaus Maria Brandauer, she made the role her own and didn’t draw on the interpretation of the role as played by Claudine Auger in Thunderball. I should point out, however, that Barbara Carrera had the flashier role as the femme fatale Fatima Blush in Never. Because of that, she had the more memorable scenes and dialogue so Basinger was somewhat overshadowed.

Coate: Where do you think Never Say Never Again ranks among the James Bond movie series?

Christie: The eighties were a period of readjustment for the Bond films, with John Glen and the rest of the creative team working to draw the tone of the series back from the larger-than-life action epics of the late seventies Moore era and closer to the Cold War ambiance of the cycle’s early sixties roots. Thus although Never Say Never Again was independent of the main Eon cycle of movies, its return to the plot and central themes of Thunderball ironically meant that it was to fit quite neatly into this overall tendency to harmonize with the qualities of the formative years of the Bond film series. Because it is clearly a remake of an existing film in the cycle, employing essentially the same plot and characters (if not the same locations), it is difficult to posit exactly where it should rank alongside other entries in the Eon series, but certainly it was a laudable attempt to introduce a more mature variation of Bond as a figure who was becoming somewhat world-weary and discontented by his life and the demands of his profession.

Cork: It is a tight race at the bottom, but when I ranked the films in 2012, Never Say Never Again came in next-to-last. Only A View to a Kill misses the mark by more. But let me be clear: every James Bond fan should watch it, endure it, and draw their own conclusions.

Pfeiffer: It’s better than some Bonds and not as good as many others. I would rank it along with Diamonds Are Forever. Both films didn’t live up to their potential but there is much to recommend about them. I suppose it’s kind of ironic that both of Connery’s big “comeback” Bond films fell somewhat flat artistically, but both seem to improve over time.

Coate: What is the legacy of Never Say Never Again?

Christie: Although Never Say Never Again was commercially successful at the time of release and enjoyed general approval amongst reviewers, over the years its reputation has proven to be increasingly divisive. This disunity of opinion may well be down to the film’s strange and often frustrating clash of characteristics. Its non-official status and advancing years of its star forced the film’s production team to be innovative in their approach, and yet the film rarely deviates too far from the conventions of the Eon films. While there is arguably greater focus upon character here than was the case in many other Eon-produced Bond films of the time, the narrative has been criticized in some quarters for seeming cluttered and confused the closer it gets to its conclusion. Ultimately, though it may well have been a brave experiment Never Say Never Again is perhaps fated to be forever known as a cinematic curiosity, standing apart from the main series of Bond movies but rarely being considered the equal of the films that had inspired it.

Cork: The legacy of Never Say Never Again is the legacy of Kevin McClory, the charming, deceitful, would-be impresario who sued his way to owning the Thunderball rights. For years, McClory tried to get his own Bond film made. He declared to many that it was he who had unlocked the secret formula for making Bond a success on film. He constantly inflated his creative contribution over that of the real screenwriter who worked with him on the original film project that became the novel Thunderball, Jack Whittingham, and that of Bond’s creator, Ian Fleming. He would go on to claim in a 1997 lawsuit that Bond’s motion picture success was due to his creative talents (and that he should be paid millions as a result). From 1976 until the release of Never Say Never Again, he not only had that story to tell, but he had Sean Connery ready and willing to return as James Bond. After many film companies tried to work with him and found it impossible, Jack Schwartzman stepped in. With Schwartzman involved and clearing up the legal hurdles over McClory’s script that bore little resemblance to the rights he held, the world opened up. Lorenzo Semple Jr., who had worked on a script inspired by Casino Royale in the 1950s and was a fantastic screenwriter (Papillion, The Parallax View, Three Days of the Condor), came onboard. Bond veteran Tom Mankiewicz did some punch-up work. After The Empire Strikes Back, Irvin Kershner was one of the most sought-after directors in the industry. Kim Basinger was primed to be a break-out star, and the rest of the cast was filled out with amazing talent. McClory, with all that help, still could not capture the magic of a James Bond film. He had input and veto power over the script, the cast, the behind-the-scenes talent, and the final cut, but his vision of Bond didn’t gel. The cool sophistication, the calmness under pressure, the underlying sense of grim determination, all seemed to vanish when McClory took the reins. He couldn’t tell his talented co-creators how to make a James Bond film because he himself didn’t understand James Bond. The legacy of Never Say Never Again is proof positive that Kevin McClory had virtually no hand in the magical formula that made James Bond an iconic cinematic character. That honor belongs to the incredible team put together by Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman. There is no greater testament to Broccoli and Saltzman’s talent than the failure of Never Say Never Again.

Pfeiffer: The film’s legacy is that it marked the final chapter of the Connery Bond film era. Whatever you feel about the movie’s shortcomings, it does have some historic importance – cinematically, that is. The movie did well at the boxoffice but was eclipsed by Octopussy, which certainly must have had Cubby Broccoli popping some champagne bottles. Roger Moore and Connery were old chums and I often wonder if Roger rubbed it in when they socialized. If there is another aspect of the legacy of the film is that it closed the chapter on Kevin McClory’s involvement with the Bond films. He tried to milk the same cow again, taking out trade ads stating he was going to turn his Thunderball rights into a Bond TV series and attempting to make a deal with Sony to do another feature film derived from Thunderball. Eon Productions sued and a long, drawn-out lawsuit commenced in America over whether he had exhausted his legal rights to screen versions of Thunderball. I became involved when I was hired by MGM to write opinions as to whether McClory could be considered to be a major influence on the development of the Bond character. This involved reading through a considerable amount of original correspondence between Ian Fleming, McClory and screenwriter Jack Whittingham when they formed a partnership in the 1950s to develop Bond screen properties. It’s all very intricate and is detailed in Robert Sellers’ excellent book The Battle for Bond. Since I had signed a non-disclosure agreement about the material I was given to study, I can’t comment on specifics except to say that I didn’t find any evidence that McClory had played any significant role in the development of the Bond character. Ultimately, in the 1990s, the court ruled in Eon’s favor and McClory was never able to launch another Bond production. Eon and MGM wisely made the choice to obtain rights to Never Say Never Again, though it is never marketed in conjunction with the Eon-related 007 films which are deemed to be “official.” To their credit, however, MGM and Eon didn’t bury the film and it has been consistently available on home video.

Coate: Thank you – Tom, John, and Lee – for participating and sharing your thoughts about Never Say Never Again on the occasion of its 35th anniversary.

The James Bond roundtable discussion will return in Remembering “From Russia with Love” on its 55th Anniversary.

IMAGES

Selected images copyright/courtesy 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, CBS-Fox Home Video, Eon Productions Limited, Los Angeles Times, MGM Home Entertainment, Taliafilm, United Artists Corporation, Warner Bros., Warner Home Video.

- Michael Coate

Michael Coate can be reached via e-mail through this link. (You can also follow Michael on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook)