The participants for this segment are (in alphabetical order)….

Jon Burlingame is the author of The Music of James Bond (Oxford University Press, 2012). He also authored Sound and Vision: 60 Years of Motion Picture Soundtracks (Watson-Guptill, 2000) and TV’s Biggest Hits: The Story of Television Themes from Dragnet to Friends (Schirmer, 1996). He writes regularly for the entertainment industry trade Variety and has also been published in The Hollywood Reporter, Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, and The Washington Post. He started writing about spy music for the 1970s fanzine File Forty and has since produced seven CDs of original music from The Man from U.N.C.L.E. for the Film Score Monthly label. His website is JonBurlingame.com.

John Cork is the author (with Maryam d’Abo) of Bond Girls Are Forever: The Women of James Bond (Abrams, 2003) and (with Collin Stutz) James Bond Encyclopedia (DK, 2007) and (with Bruce Scivally) James Bond: The Legacy (Abrams, 2002). He is the president of Cloverland, a multi-media production company. Cork also wrote the screenplay to The Long Walk Home (1990), starring Whoopi Goldberg and Sissy Spacek, and wrote and directed the feature documentary You Belong to Me: Sex, Race and Murder on the Suwannee River for producers Jude Hagin and Hillary Saltzman (daughter of original Bond producer, Harry Saltzman). He contributed new introductions for the original Bond novels Casino Royale, Live and Let Die, and Goldfinger for new editions published in the UK by Vintage Classics in 2017.

Lee Pfeiffer is the author (with Dave Worrall) of The Essential Bond: The Authorized Guide to the World of 007 (Boxtree, 1998/Harper Collins, 1999) and (with Philip Lisa) The Incredible World of 007: An Authorized Celebration of James Bond (Citadel, 1992) and The Films of Sean Connery (Citadel, 2001). Lee was a producer on the Goldfinger and Thunderball Special Edition LaserDisc sets and is the co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of Cinema Retro magazine, which celebrates films of the 1960s and 1970s and is “the Essential Guide to Cult and Classic Movies.”

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

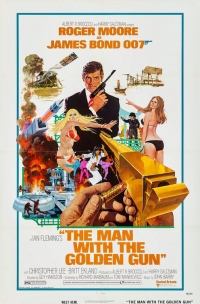

And now that the participants have been introduced, might I suggest preparing a martini (shaken, not stirred, of course) and cueing up the soundtrack album to The Man with the Golden Gun, and then enjoy the conversation with this group of James Bond authorities.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): In what way is The Man with the Golden Gun worthy of celebration on its 45th anniversary?

Jon Burlingame: The ninth Bond film was also Roger Moore’s second outing as 007; Guy Hamilton’s fourth and final time directing a Bond film; producer Harry Saltzman’s last film in the franchise he helped launch; and the seventh of John Barry’s eleven Bond scores. Those facts alone are worth recounting as we remember this installment. Hamilton had firmly established the Bond style with Goldfinger, but it was his trio of Diamonds Are Forever, Live and Let Die and Golden Gun that saw a decisive shift away from serious Bond in the direction of lighthearted Bond, which would continue throughout the 1970s.

John Cork: There is the off-chance on this forty-fifth anniversary, someone will dust off their old 8-Track copy of Alice Cooper’s Muscle of Love album and listen to his rejected title song for The Man with the Golden Gun while joy-riding in a red AMC Hornet wearing a leisure suit, and if they do, I want them to find me and invite me to sit shotgun. The Man with the Golden Gun is not a great film. It is not even a good film. But it is a film to be watched. Why? It is an amazing time capsule every self-righteous Twitter Social Justice Warrior should endure to educate themselves of just how far we’ve come. It was a film whose joints creaked with age when it opened, and it marked the end of an era with Bond, the last 007 hurrah for Harry Saltzman, for Guy Hamilton, for cinematographer Ted Moore, and for their allies in the Bond family. It embraces some of the worst sexist tropes (Britt Ekland’s painful “dumb blonde” Mary Goodnight) and quasi-racist characterizations (how many subservient “funny” Asians can you pack into one Bond film?). It feels small (Scaramanga and his army of one Jesse Jackson look-alike), inelegant (Phuyuck sparkling wine), lacking in the sharp observational humor that made every previous Bond film feel sophisticated (“Mexican screw-off”?). It also — far more than the blaxploitation-inspired Live and Let Die — feels derivative of the success of the B-film kung-fu craze, and, even so, lacks compelling fight scenes.

Yet, The Man with the Golden Gun has aged with some grace well beyond other Bond films. There is Barry’s hit-and-miss score, that in places is as rich and dreamy as his best work from the 1960s. There is the surprising savageness in Roger Moore’s sophomore performance. There is the enduring charm of Hervé Villechaize’s Nick Nack, and the other-worldly beauty of the spires of Phang Nga Bay in Thailand. And there is the imperious grace of Sir Christopher Lee. Celebrate The Man with the Golden Gun for its failures and successes, for all that is right and wrong in the film, but celebrate it most for what it is: a glimpse at the Western values of 1974 through the lens of the Bond filmmakers wrestling with their own sense of relevance.

Lee Pfeiffer: I suppose any Bond movie lingers in movie history and therefore has a special significance. It’s the worst Bond movie ever made, in my opinion, but it was successful enough to prove that the audience that had made Live and Let Die a major success wasn’t just due to curiosity about seeing Roger Moore’s interpretation of the role. If nothing else, it cemented that audiences had accepted him as Sean Connery’s successor.

Coate: What do you remember about the first time you saw The Man with the Golden Gun?

Coate: What do you remember about the first time you saw The Man with the Golden Gun?

Burlingame: It must have been in early 1975, since it opened in London in December 1974 and my market tended to get new releases a few weeks later. In those days, remember, a new Bond film was an event. And few films could match the exotic locales, the gorgeous women, the diabolical villains and the high-energy action sequences you would always get with a Bond film. So there was automatic excitement — and also something of a letdown for those of us who took our Bond seriously.

The Moore quips (“Phu-yuck,” “She’s just coming, sir,” etc.) diminished the 007 mystique for some of us; now when I go back and watch again I find them almost charmingly nostalgic. The return of hick sheriff J.W. Pepper really irritated me (and frankly still does). I didn’t mind Hervé Villechaize as Scaramanga’s diminutive sidekick Nick Nack. Tom Mankiewicz’s autobiography makes it clear that he wrote most of the script and that Richard Maibaum did the polish (they’re both credited) and so a good deal of the blame — if we should call it that — is really Tom’s.

What links this film most strongly to the 1960s Bond that we grew up with and revered is John Barry’s score. It’s no Goldfinger or On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, of course, because jam-packed schedules gave him only about three weeks to write and record it. The title song alone was done very quickly, as I discuss in my Bond music book. It’s nobody’s favorite Bond song, of course, but it’s still Barry & Don Black and that’s always worthwhile. The score is, as always with Barry, mostly classy (except for that awful slide whistle during the car chase, which he later regretted), and has wonderful moments. Get out the soundtrack album and listen to In Search of Scaramanga’s Island, one of the most haunting and effective Barry cues of the 70s Bonds. Similarly, the funhouse sequences are beautifully scored, and the album track that’s not in the movie, the Dixieland jazz version of the title theme, is simply delightful. John Barry always delivered, and Man with the Golden Gun was no exception.

Cork: I was thirteen and gathered a couple of friends on the Wednesday it opened at the Capri Theater in Montgomery, Alabama. We went to the first evening show, which was a big deal on a school night just before Christmas break. I had read all the Bond novels twice by then. There had never been a film that had me more excited. I felt certain I would see it more times in the theater than I had seen The Sting or American Graffiti or Billy Jack. United Artists could not have paid a publicist to have done a better job pre-selling the film at my school. And, of course, I loved it. I recall describing the film scene-by-scene to friends the next day, explaining how great it was to anyone who would listen. But a funny thing: I only saw it that one time on its first run. Something inside me never made the effort to see it that second, third, fourth time in the theater. I was simply too big of a fan at that age to admit that the movie failed to live up to my hopes and dreams, failed to do the most important thing it needed to do: feel like a James Bond film.

Pfeiffer: My friend and I went to see it on opening day. We had very much liked Live and Let Die and were expecting to have an enthusiastic reaction to Golden Gun. We liked the idea of Christopher Lee playing the villain, though there was trepidation over the fact that the Sheriff Pepper character was returning. We enjoyed Clifton James’s performance in the previous film but we couldn’t imagine a scenario in which he could logically be brought back. Our fears proved to be justified but the film had self-destructed long before that. Even the pre-credits scene was unsatisfying due to having Roger Moore pose as a wax figure of himself, which literally never works as a gimmick on screen in any movie. The kung fu school battle starts out well and I liked Bond’s escape but then the teenage girls enter the picture and start bashing the villains. It was cringe-inducing even in 1974. I also realized many years later when I was writing a book about the Bond films just how nasty everyone is in the film, even the lovable regulars. Moneypenny comes across like Cruella de Vil, “M” is so grumpy that I believe at one point he calls “Q” an idiot. Bond slaps around Andrea. It’s as though they are rebelling against the script. There’s also a cheap look to the film, even though we know it cost a lot of money to bring to the screen. Scaramanga’s island HQ never looks very impressive and it’s manned by one innocuous henchman. Shall I go on? John Barry’s score is atmospheric but it’s undercut by the awful lyrics to the title song, the only disappointing song the legendary Don Black ever contributed to. I recall waiting in vain for the film to improve by the climax but when Bond suffers the indignity of getting kicked in the rump by Nick Nack, I knew it was a lost cause.

I hadn’t seen the film in its entirety in probably twenty-five years or more. Recently, it was telecast on Turner Classic Movies so I kept it on thinking I might have a different viewpoint. Alas, it was not to be. I couldn’t get through the entire film. Are there any good aspects? Yes, the locations are exotic and some of the witticisms are quite amusing. Christopher Lee and Maud Adams both give commendable performances but it’s a shame they were not used in a better film. There have been weaknesses in Bond movies before, to be sure. You have to expect that when a series has been going on for almost sixty years. But even the weakest Bonds generally have enough merits to make me find them enjoyable. I guess I’ll never come around with Golden Gun, however.

Coate: In what way was Christopher Lee’s Scaramanga a memorable villain?

Burlingame: I think we all rejoiced that such a distinguished British actor had been chosen to be the new Bond villain, and there’s no question that Lee brought immense class and prestige to the film. Lee was every bit as great as Gert Frobe or Donald Pleasence, maybe better, as an assassin involved with a powerful solar weapon (although I wish they could have come up with a better label than “solex agitator,” which sounds like my washing machine). I am sure that Lee himself was relieved to be part of a major British film franchise that was far afield from the Hammer horror films he’d been doing. Had the part, and the movie, been better, perhaps Lee would rank among the best Bond villains ever.

Cork: Christopher Lee, through marriage, was a cousin of Ian Fleming. They golfed together on occasion. He was the most well-known actor at the time to play a Bond villain, more famous in 1974 through his work with Hammer, whose films were well-distributed in the United States, than any prior Bond villain actor. Lee dominates every scene he’s in. I am not much of a fan of the “we are not so different, you and I” villains in the Bond series, although Lee makes it work better than any other actor until Javier Bardem’s performance as Silva in Skyfall (a character partially inspired by both the literary and cinematic Scaramanga). As much as I love Guy Hamilton, Tom Mankiewicz and Richard Maibaum, Lee gets full credit for this. While the wonderful dialog where he describes learning that he loved killing leaps off the page, much of the rest is pedestrian stuff that Lee infuses with a Jeffery Epstein-like charm that lures in viewers, in spite of their boredom with his ho-hum scheme and poor taste in cars.

One must mention Hervé Villechaize’s staggering performance of Nick Nack. His rapturous joy at simply messing with the heads of everyone, including Scaramanga, makes him an infuriatingly wonderful henchman. His devilish nature always makes me wish for more. Nick Nack is a wonderfully written character, fleshed out in glorious evilness, always well-turned-out, always with great dialog, and always with the perfect expression on his face.

One of my favorite production stories which we could not include on the DVDs occurred in the lobby of a hotel as the crew returned from shooting. Hervé, who was notorious for his late-night carousing in Hong Kong and Bangkok, was walking beside Maud Adams. He looked up at her and said loudly that one day he was going to make mad, passionate love to her. Maud looked down at Hervé, and, without missing a beat, said, “If you do, and I find out about it, I will be very upset.” That one line from Maud is far and away the funniest dialog associated with the film.

Pfeiffer: Lee was excellent in the role, as he was in any role. A consummate professional. If the script had been better, he could have emerged as a classic villain. The film comes to life when Lee shares the screen with Roger Moore. They were old friends and very much enjoyed working together. One time Dave Worrall and I were having lunch with Christopher in London. He said to me (I’m paraphrasing), “I shouldn’t be dining with you, Lee. I read a newspaper article in which you were quoted as saying my Bond film was one of the worst.” To which I replied, “I never said it was one of the worst, Christopher. I said it was the worst.” I did remind him, however, that I had been complimentary about his performance. I was able to wring another laugh at the film’s expense some years ago at a surprise birthday party for Roger Moore in New York. When he saw me, he feigned outrage by pretending to blame me for a bad business deal that had cost him some money. “Please forgive me, Roger,” I responded. “After all, I forgave you for The Man with the Golden Gun!”

Coate: In what way was Britt Ekland’s Mary Goodnight (or Maud Adams’ Andrea Anders) a memorable Bond Girl?

Burlingame: They were an interesting combination — both born in Sweden, close to the same age, both doing lots of small parts and then making a huge international splash with the Bond film. Adams was a terrific choice as Scaramanga’s mistress (later to return, memorably, as the title character in Octopussy) and Ekland, perceived as a lightweight by comparison, was actually fine as Mary Goodnight because her character is a cute but incompetent assistant. She’s acceptable but the character reduces the film, at times, to TV sitcom levels.

Cork: Britt Ekland is one of the most beautiful women in the world. In 1974, she had everything one could hope for in casting a strong, beautiful, sexy actress in a Bond film. She also had the fantastic distinction of having been married to an actor cast as James Bond (née, Evelyn Tremble) — Peter Sellers from 1967’s Casino Royale. Britt did not fail the film. The film failed her. She plays the identical part as the late Sharon Tate in the 1969 Matt Helm film, The Wrecking Crew, the ditzy, beautiful assistant who bungles up things more than she helps, but who finds herself hopelessly in love with our hero, and in the end she winds up in his arms. Goodnight was a wonderful character in the novels, and I will always regret that her charm was stripped away for this film, replaced by painful clichés (bikini and heels, anyone?). A low-point for the portrayal of women in the series is her bum turning on the solar powered high-energy beam. But worse is the utter lack of dignity afforded her by Bond. After clearly deciding to use her for his momentary pleasure, he stuffs her in a closet when Andrea Anders shows up. She not only gets to hear Bond performing his sexual gymnastics a few feet away, but Bond does not even let her out of said closet until after Andrea has left the hotel and returned to Scaramanga’s boat some distance away. It is appalling behavior not on the part of the fictional 007, but on the part of the filmmakers who seemed to think this was going to be knee-slapping fun for the audience.

Maud Adams fares much better as Andrea Anders, but is given too little to do in an underwritten part. Yet, she imbues the role with both pathos and passion. Both actresses hold the screen, acquit themselves well, and deserved better.

Pfeiffer: The thankfully short-lived tradition of presenting the leading female characters as ditzy began with Jill St. John’s Tiffany Case in Diamonds Are Forever. Until then, the heroines were brave, brainy and independent. Unfortunately, the character of Mary Goodnight made Tiffany look like a Rhodes Scholar. I never liked the idea of pairing Bond with a woman whose only assets were physical. I felt the films in which that occurred compromised the movie as a whole in return for getting a few quick laughs. Certainly Britt was capable of giving a commendable dramatic performance but her character was so simple-minded there wasn’t much she could do with it. By contrast, Maud Adams’ Andrea is a far more realistic and sympathetic character.

Coate: Where do you think Golden Gun ranks among the James Bond movie series?

Coate: Where do you think Golden Gun ranks among the James Bond movie series?

Burlingame: In the bottom half, for sure. Yet because of Moore and Lee and Barry and the locations, way above some of the Brosnan entries, the grimly violent Licence to Kill and a few others I find hard to tolerate. The film certainly looks great, having been shot in Thailand, Hong Kong and Macau, and Barry’s score elevates the entire enterprise.

Cork: I ranked it 18th when I did a marathon with my son in 2012. He ranked it higher, 13th, at that time, and he was the same age as when I first saw the film. For me, there are too many wincing moments: the penny-whistle during the film’s signature stunt (the Astro-Spiral Jump), the ill-conceived cross-promotion deal with AMC, The Man from U.N.C.L.E.-quality fight in the backlot version of Beirut, the painfully un-Bondian karate-girls fight scene, the deeply unwarranted reappearance of Sheriff J.W. Pepper, the line, just months after Nixon’s resignation, “We’re Democrats, Maybell,” the irritating, illogical false suspense scenes, the utter ease with which Bond and Goodnight are captured by Scaramanga over and over, and the funhouse. Oh, for the love of all, I simply hate the funhouse. Crueler critics did note that only Roger Moore could convincingly play a mannequin. On the plus side, Peter Murton’s other sets were often inspired (by Ken Adam, but they look perfectly Bondian). Many of the locations are gorgeous, and it is a consistently beautiful film to watch in terms of lighting, despite the firing of Ted Moore (who was losing a battle with alcoholism at the time) after the location work in Thailand, replacing him with the monumental talent of Oswald Morris for the studio work.

Pfeiffer: As I previously stated, in my opinion, it’s the worst but at least it’s the worst of a good lot. After all, in any franchise, one film has to be the worst. The ability of the producers over so many years to come up with winners allows for a few misses every now and then.

Coate: What is the legacy of The Man with the Golden Gun?

Burlingame: It seems incredible that Golden Gun was the ninth of 25 Bond films, and that it was 45 years ago that I was sitting in the theater hoping for a classic 007 picture. I think of the legacy as “early Roger Moore” (his second time in the tux), a very classy performance by Christopher Lee, John Barry attempting to bring some Bond dignity to the sillier moments — in effect “marking time” for us, after experiencing several great Bond films while awaiting a return to greatness and hoping this grand Fleming-fueled adventure wasn’t about to fizzle and burn out in mediocrity.

Cork: The Man with the Golden Gun has a spectacular legacy for a mediocre film. That legacy started in 1976 when ABC used the movie as “inspiration” for the development of its series, Fantasy Island, casting Hervé Villechaize as the Nick Nack-like Tattoo who serves as the mysterious aide-de-camp to the leisure-suited Mr. Rourke. The initial Fantasy Island television film aired in early-January, 1977, and was heavily promoted during the premiere showing of The Man with the Golden Gun on ABC. The TV movies and then the show were massive hits, revitalized in 1998, and re-envisioned as a horror film for 2020. In Thailand, the small town of Phuket launched their tourist trade largely off the back of The Man with the Golden Gun, one of the biggest tours being trips to “James Bond Island,” where visitors can buy numerous t-shirts and trinkets from beach vendors. Maud Adams, of course, returned to the Bond franchise in a larger role in Octopussy. Nick Nack clearly inspired Mini Me from the Austin Powers films. The film, The Trip, features actors Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon quoting hunks of dialog from The Man with the Golden Gun. The making of the film played a key part in the HBO movie about the tragic life of Hervé Villechaize, My Dinner with Hervé.

Yet, the ultimate legacy may be in the question frequently asked on the internet: “Where is my flying car?” One of the coolest scenes in The Man with the Golden Gun is the transformation of Scaramanga’s AMC Matador into a personal plane before it takes off into the wild blue yonder. This stunt was going to be performed for real. The actual flying car was, if you can believe it, a Ford Pinto with modified Cessna Skymaster wings, engine, and tail structure that attached by “never fail” bolts to the car. The inventors, Henry Smolinski and Harold Blake, dubbed the contraption, the AVE Mizar. At press events, Smolinski and Blake were peppered with questions about the wisdom of flying anything which was designed to have the wings and flight engine easily removed. These queries were quickly brushed aside. These men were engineers. They knew what they were doing. They inked a deal to appear in the next Bond film. To prepare for their big-screen debut, on September 11, 1973, Smolinsky and Blake took off from Ventura County Airport. They did not get far. The crash report states the following: “Type of accident: AIRFRAME FAILURE: IN FLIGHT.” I often think of that moment when Smolinski and Blake heard the rending of metal, and then the sound of the engine growing distant as the wings detached from the car and they were left to ponder the glide angle of a Ford Pinto and the cruelty of having gravity as your mistress. For years they had labored, believed, dreamed, toiled, to be up — up high in the sky in their flying car with detachable wings. They had convinced themselves that this would be their destiny. And, of course, it was. Thoughts of destiny likely filled their minds as all the flaws in their plans came into sharp focus during a few fateful seconds of a Wile E. Coyote freefall. They did not survive the crash.

It takes great faith, labor, effort, and passion to make even a middling movie. But at the end of the day, if one fails, the worst crime is to have lost investors some money and wasted the time of some ticket-buyers. The Man with the Golden Gun may not be a particularly good Bond film, but for some, it is remembered fondly and re-watched with joy. It may have lots of design flaws, but the wings stay on and it lands safely. The film underperformed at the box office but did will enough. Bond survived for further adventures. As the inventors of the AVE Mizar would, I’m sure, attest if they could, survival is good enough, and, in fact, it is often the greatest legacy of all.

Pfeiffer: One time, Cubby Broccoli had asked me what my least favorite Bond film was. When I said without hesitation it was Golden Gun, I remember him chuckling. He didn’t agree with me, but I think it was meaningful that he didn’t disagree, either. I think the film’s legacy is important in that I believe Cubby knew the movie wasn’t as well received as most Bond films were. While it was successful, grosses were lower than for the earlier films. Cubby was going through the tumultuous break-up of his partnership with Harry Saltzman and that might have compromised the film. But he told me he read letters from fans and took to heart their sentiments. I’ve always suspected that negative reaction towards the film inspired him to take his time with the next one, The Spy Who Loved Me. As his first solo production in the franchise as producer, he brought back the style and grandeur of the earlier movies. The response was universal acclaim and sky high boxoffice receipts. Perhaps the anemic response to Golden Gun is its real legacy, as it seems to have saved the series. If the next film had been equally flawed, the franchise might not have recovered, let alone regain the kind of popularity it hasn’t enjoyed since the 1960s. To be fair, people whose opinions I respect like the film, so maybe they are more insightful than I am. My daughter Nicole grew up surrounded by elements of the Bond series and the people associated with them and she attended all the royal premieres in London for the Brosnan films. Yet, she probably hasn’t seen at least half the movies. Many years ago, she said the Bond film she likes most was Man with the Golden Gun. I have never felt like such a failure as a parent. Fortunately, she now says Skyfall is her favorite. So I guess we can be on speaking terms again.

Coate: Thank you — Jon, John, and Lee — for participating and sharing your thoughts about The Man with the Golden Gun on the occasion of its 45th anniversary.

The James Bond roundtable discussion will return.

IMAGES

Selected images copyright/courtesy 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, CBS-Fox Home Video, Danjaq LLC, Eon Productions Limited, MGM Home Entertainment, New York Daily News, United Artists Corporation.

SPECIAL THANKS

John Hazelton

- Michael Coate

Michael Coate can be reached via e-mail through this link. (You can also follow Michael on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook)