Finally, there is an interview segment with a quartet of film historians and Kubrick authorities who discuss the film’s impact and influence.

2001 NUMBER$

- 1= Box-office rank among films directed by Stanley Kubrick

- 1 = Number of Academy Awards

- 1 = Number of sequels

- 1 = Rank among top-earning films of 1968 (lifetime earnings)

- 1 = Rank on AFI’s Top Sci-Fi Films

- 3 = Number of theaters showing 2001 during opening week

- 4 = Number of Academy Award nominations

- 6 = Rank among MGM’s all-time top-earning movies at close of original run

- 10 = Rank among top-earning films of 1968 (calendar year)

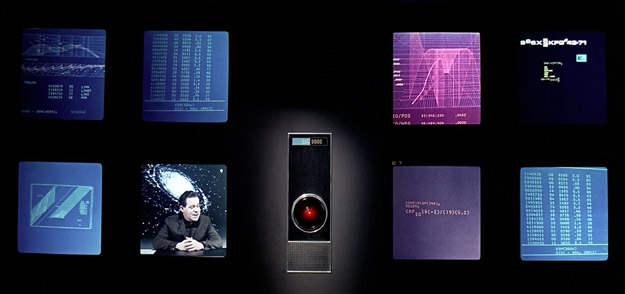

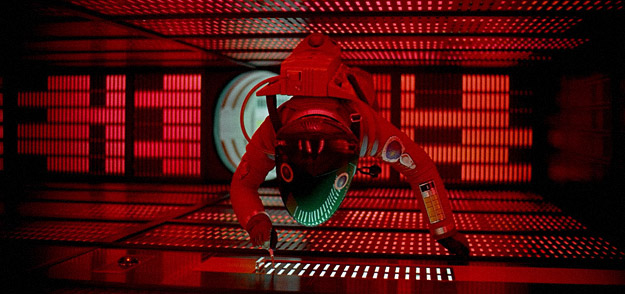

- 13 = Rank of HAL 9000 on AFI’s 100 Greatest Villains

- 17 = Peak all-time box-office chart position

- 22 = Rank on AFI’s 100 Greatest American Movies of All Time

- 33 = Rank among top-earning movies of the 1960s (earnings from 1/1/60 – 12/31/69)

- 103 = Number of 70mm prints for domestic first-run

- 127 = Number of weeks of longest-running engagement

- 148 = Rank on current list of all-time top-grossing films (adjusted for inflation)

- $8.5 million = Box-office rental (through 12/31/68)

- $12.0 million = Production cost

- $14.5 million = Box-office rental (through 12/31/69)

- $17.5 million = Box-office rental (through 12/31/70)

- $21.5 million = Box-office rental (through 12/31/71)

- $24.1 million = Box-office rental (through 12/31/80)

- $25.5 million = Box-office rental (through 12/31/96)

- $56.9 million = Box-office gross (lifetime)

- $85.9 million = Production cost (adjusted for inflation)

- $155.5 million = Box-office rental (adjusted for inflation)

- $407.1 million = Box-office gross (adjusted for inflation)

A SAMPLING OF MOVIE REVIEWER QUOTES

“Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is the picture which science-fiction enthusiasts of every age and in every corner of the world have prayed (sometimes forlornly) that the industry might one day give them.” — Charles Champlin, Los Angeles Times

“2001: A Space Odyssey is a thoroughly uninteresting failure, and the most damning demonstration yet of Stanley Kubrick’s inability to tell a story coherently and with a consistent point of view. His film is not a film at all, but merely a pretext for a pictorial spread in Life magazine.” — Andrew Sarris, Village Voice

“Kubrick’s special effects border on the miraculous — a quantum leap in quality over any other science fiction film ever made!” — Joseph Morgenstern, Newsweek

“The movie is so completely absorbed in its own problems, its use of color and space, its fanatical devotion to science-fiction detail, that it is somewhere between hypnotic and immensely boring.” — Renata Adler, The New York Times

“A fantastic movie about man’s future! An unprecedented psychedelic roller coaster of an experience!” — Life

“A film that is so dull, it even dulls our interest in the technical ingenuity for the sake of which Kubrick has allowed it to become dull.” — Stanley Kauffmann, The New Republic

“2001: A Space Odyssey provides the screen with some of the most dazzling visual happenings and technical achievements in the history of the motion picture!” — Time

“Is a work of art possible if pseudo-science and the technology of moviemaking become more important to the ’artist’ than man? This is central to the failure of 2001. It’s a monumentally unimaginative movie: Kubrick, with his $750,000 centrifuge, and in love with gigantic hardware and control panels, is the Belasco of science fiction.” — Pauline Kael, The New Yorker

“2001: A Space Odyssey is a gorgeous, exhilarating and mind-stretching spectacle.” — Emerson Beauchamp, The Washington Star

“A regrettable failure, although not a total one. This film is fascinating when it concentrates on apes and machines…and dreadful when it deals with the in-betweens: humans.” — John Simon, New Leader

“A uniquely poetic piece of sci-fi…hypnotically entertaining!” — Penelope Gilliatt, The New Yorker

“2001: A Space Odyssey is not a cinematic landmark. It compares with, but does not best, previous efforts at science fiction; lacking the humanity of Forbidden Planet, the imagination of Things to Come and the simplicity of Of Stars and Men, it actually belongs to the technically-slick group previously dominated by George Pal and the Japanese.” — Robert B. Frederick, Variety

“2001: A Space Odyssey is without a doubt one of the most controversial, enigmatic and cinematically impressive films ever made. Kubrick spent four years and $10 million putting it together and the result is 140 minutes of technical achievement that is a milestone in movie history.” — John Hinterberger, The Seattle Times

“The sound track is a mish-mash of pseudo-church electronic music and, incredibly, Strauss waltzes. Imagine whirling through space to schmaltz in three-quarter time!” — Kathleen Carroll, New York Daily News

“Since 2001: A Space Odyssey has a somewhat grandiose title and a rather antiseptic start, there’s no hint of its eventual entertainment. It turns out to the ultimate in science-fiction.” — Alta Maloney, The Boston Herald

“Lacking a focus and conclusion that can be understood, the picture wanders and exhausts its audience. Since this the first time that director Stanley Kubrick has lost touch with any large part of the audience, one can only guess that the space journey theme hypnotized him. And while under this mighty influence he stubbed his toe.” — Archer Winsten, New York Post

“The fascinating thing about this film is that it fails on the human level but succeeds magnificently on a cosmic scale.” — Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

“Kubrick’s futuristic film operates on three levels: The scientific, the philosophic and the dramatic. In my opinion, it is more successful on the first two levels than on the third, but two for three is good enough for the major leagues — and Kubrick definitely is a major leaguer.” — James Meade, The San Diego Union

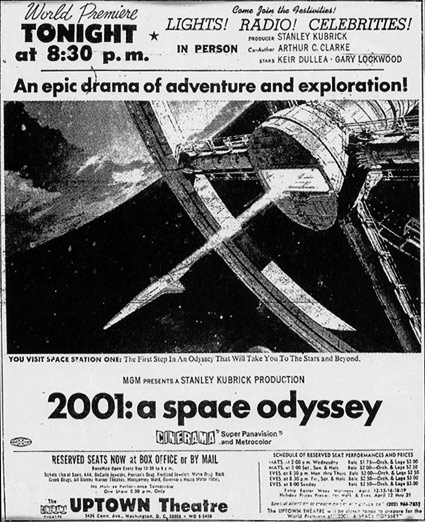

THE ORIGINAL 70MM ENGAGEMENTS

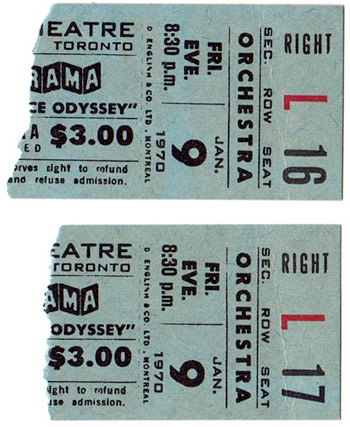

Presented here is a chronological listing of 2001: A Space Odyssey’s North American first-run 70-millimeter six-track stereophonic sound presentations. These were “hard ticket” roadshow engagements (except where noted otherwise) and were special, long-running, showcase presentations in major cities prior to the film being exhibited as a general release, and they featured advanced admission pricing, an overture/intermission/entr’acte/exit music, and an average of just ten scheduled screenings per week. As well, souvenir program booklets were sold. (There were also roadshow engagements of 2001 that utilized standard 35mm prints but these have not been included in this work.)

Out of the hundreds of films released during 1968, 2001 was among only fourteen that were given deluxe roadshow treatment and among only eleven released with 70mm prints. The duration of these engagements (measured in weeks) has been included for most of the entries to give a sense of how successful the film was in its first phase of release.

The film’s anniversary offers an opportunity to namedrop some famous cinemas (nearly all of which are now closed), to offer some nostalgia for those who saw the film during this phase of its original release, and to reflect on how the film industry has evolved the manner in which event and prestige films are treated.

Opening date YYYY-MM-DD … City — Cinema (duration in weeks)

m/o = a move-over engagement (i.e. a continuation of a booking from another cinema in same city/market)

*Advertised as a Cinerama presentation

**Advertised as a 70mm presentation

***Presentation format unadvertised

****Advertised as a Vistarama presentation

*****Advertised as a Dimension 150 presentation

- 1968-04-02 … Washington, DC — Uptown* (52)

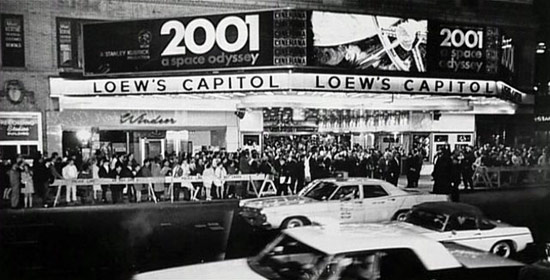

- 1968-04-03 … New York, NY — Capitol* (24)

- 1968-04-04 … Los Angeles, CA — Warner Hollywood* (80)

- 1968-04-10 … Boston, MA — Boston* (36)

- 1968-04-10 … Denver, CO — Cooper* (47)

- 1968-04-10 … Detroit, MI — Summit* (47)

- 1968-04-10 … Houston, TX — Windsor* (31)

- 1968-04-11 … Chicago, IL — Cinestage* (36)

- 1968-05-22 … Philadelphia, PA — Randolph* (30)

- 1968-05-28 … San Diego, CA — Center* (44)

- 1968-05-28 … Seattle, WA — Cinerama* (77)

- 1968-05-29 … Atlanta, GA — Martin Cinerama* (22)

- 1968-05-29 … Baltimore, MD — Town* (20)

- 1968-05-29 … Cincinnati, OH — International 70* (19)

- 1968-05-29 … Dallas, TX — Capri* (24)

- 1968-05-29 … Miami Beach, FL — Sheridan* (23)

- 1968-05-29 … Montreal, QC — Imperial* (24)

- 1968-05-29 … New Orleans, LA — Cinerama* (29)

- 1968-05-29 … Providence, RI — Cinerama* (20)

- 1968-05-29 … St. Louis, MO — Cinerama* (29)

- 1968-05-29 … Scottsdale, AZ — Kachina* (25)

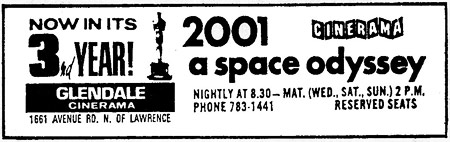

- 1968-05-30 … Toronto, ON — Glendale* (127)

- 1968-06-06 … Charlotte, NC — Carolina* (13)

- 1968-06-07 … Honolulu, HI — Cinerama* (29)

- 1968-06-12 … Birmingham, AL — Eastwood Mall* (8)

- 1968-06-12 … Columbus, OH — Grand* (27)

- 1968-06-12 … Dayton, OH — Dabel* (20)

- 1968-06-12 … Harrisburg, PA — Trans-Lux* (15)

- 1968-06-12 … Jacksonville, FL — 5 Points* (14)

- 1968-06-12 … Kansas City, MO — Empire 2* (27)

- 1968-06-12 … Pittsburgh, PA — Warner* (22)

- 1968-06-12 … Salt Lake City, UT — Villa* (22)

- 1968-06-12 … Tampa, FL — Palace* (15)

- 1968-06-12 … Toledo, OH — Showcase 1* (14)

- 1968-06-13 … Portland, OR — Hollywood* (42)

- 1968-06-19 … Buffalo, NY — Century* (13)

- 1968-06-19 … Cleveland, OH — State* (21)

- 1968-06-19 … Hartford, CT — Cinerama* (26)

- 1968-06-19 … Norfolk, VA — Rosna* (25)

- 1968-06-19 … Omaha, NE — Indian Hills* (17)

- 1968-06-19 … San Francisco, CA — Golden Gate* (73)

- 1968-06-19 … Wichita, KS — Uptown* (15)

- 1968-06-26 … Calgary, AB — North Hill* (14)

- 1968-06-26 … Des Moines, IA — River Hills* (20)

- 1968-06-26 … Fresno, CA — Warnor* (17)

- 1968-06-26 … Hicksville, NY — Twin South* (39)

- 1968-06-26 … London, ON — Park* (8)

- 1968-06-26 … Louisville, KY — Showcase 1* (14)

- 1968-06-26 … Milwaukee, WI — Wisconsin 1* (25)

- 1968-06-26 … Sacramento, CA — Esquire* (35)

- 1968-06-26 … St. Louis Park, MN — Cooper* (31)

- 1968-06-26 … Syracuse, NY — Eckel* (10)

- 1968-06-26 … Tulsa, OK — Fox* (15)

- 1968-06-26 … Vancouver, BC — Capitol* (15)

- 1968-06-27 … Indianapolis, IN — Indiana* (20)

- 1968-06-27 … Nashville, TN — Belle Meade* (13)

- 1968-06-28 … Huntsville, AL — Westbury* (9)

- 1968-07-02 … Las Vegas, NV — Cinerama* (15)

- 1968-07-10 … Chattanooga, TN — Brainerd* (11)

- 1968-07-11 … Shreveport, LA — Broadmoor** (8)

- 1968-07-16 … Oklahoma City, OK — Cooper* (33)

- 1968-07-17 … Montclair, NJ — Clairidge* (36)

- 1968-07-17 … San Antonio, TX — North Star II** (18)

- 1968-07-18 … Richmond, VA — Westhampton*** (10)

- 1968-07-23 … San Jose, CA — Century 21* (87)

- 1968-07-24 … Knoxville, TN — Capri-70* (9)

- 1968-07-24 … Raleigh, NC — Ambassador** (10)

- 1968-07-25 … Memphis, TN — Paramount**** (11)

- 1968-07-25 … Winnipeg, MB — Garrick** (8)

- 1968-07-31 … Evansville, IN — Ross*** (8)

- 1968-07-31 … West Springfield, MA — Showcase 1* (12)

- 1968-08-07 … Springfield, IL — Esquire** (8)

- 1968-08-09 … Grand Forks, ND — Cinema International**

- 1968-08-09 … Orlando, FL — Beacham* (11)

- 1968-08-14 … Austin, TX — Americana** (13)

- 1968-08-21 … Albany, NY — Hellman** (12)

- 1968-08-21 … Cuyahoga Falls, OH — Falls* (17)

- 1968-08-22 … Grand Rapids, MI — Eastbrook** (6)

- 1968-08-22 … Lubbock, TX — Winchester*** (11)

- 1968-08-28 … Lawrence, MA — Showcase 1* (12)

- 1968-09-04 … Reno, NV — Century 21* (9)

- 1968-09-16 … New York, NY — Cinerama* (m/o from Capitol, 13 [37])

- 1968-09-18 … Worcester, MA — Showcase 2* (13)

- 1968-09-25 … Edmonton, AB — Paramount** (8)

- 1968-09-25 … Hamden, CT — Cinemart** (13)

- 1968-09-25 … Ottawa, ON — Nelson** (12)

- 1968-09-25 … Youngstown, OH — Paramount** (8)

- 1968-09-27 … Reading, PA — Fox** (5)

- 1968-10-02 … Albuquerque, NM — Fox Winrock* (13)

- 1968-10-02 … Lexington, KY — Strand*** (7)

- 1968-10-02 … Scranton, PA — Strand** (5)

- 1968-10-09 … El Paso, TX — Fox Bassett Center*** (11) [unreserved seating]

- 1968-10-17 … Penfield, NY — Panorama* (17)

- 1968-10-25 … St. Petersburg, FL — Center** (9)

- 1968-10-30 … Eugene, OR — Oakway*** (4) [unreserved seating]

- 1968-10-30 … Fargo, ND — Cinema 70* (5)

- 1968-10-30 … Little Rock, AR — Cinema 150***** (7) [unreserved seating]

- 1968-10-30 … Milan, IL — Showcase 1* (7)

- 1968-11-06 … Corpus Christi, TX — Deux Cine II*** (7)

- 1968-11-06 … Monterey, CA — Cinema 70*** (13)

- 1968-11-07 … Greensboro, NC — Terrace** (3) [unreserved seating]

- 1968-11-08 … Cedar Rapids, IA — Times 70*** (9)

- 1968-11-08 … Columbia, SC — Richland Mall** (3) [unreserved seating]

- 1968-11-13 … Waco, TX — 25th Street*** (4) [unreserved seating]

- 1968-11-14 … Augusta, GA — National Hills** (6) [unreserved seating]

- 1968-11-20 … Tucson, AZ — El Dorado*** (9)

- 1968-12-18 … Nanuet, NY — Route 59** (9)

- 1968-12-20 … Kokomo, IN — Markland Mall II** (3) [unreserved seating]

- 1968-12-29 … Odessa, TX — Grandview*** (3)

- 1968-12-31 … Mason City, IA — Park 70** (2) [unreserved seating]

- 1969-01-08 … Wichita Falls, TX — State*** (3) [unreserved seating]

- 1969-01-09 … North Charleston, SC — Pinehaven*** (3) [unreserved seating]

- 1969-01-15 … Hamilton, ON — Centre Twin West** (8)

- 1969-02-19 … Modesto, CA — Briggsmore** (5) [unreserved seating]

- 1969-02-19 … St. Cloud, MN — Cinema 70** (2) [unreserved seating]

- 1969-03-14 … Colorado Springs, CO — Ute 70*** (4) [unreserved seating]

- 1969-09-30 … Oakland, CA — Century 21* (11)

- 1969-10-14 … Orange, CA — Cinedome 21* (27)

- 1969-10-29 … Beverly Hills, CA — Beverly Hills** (m/o from Warner Hollywood, 23 [103])

- 1969-11-11 … San Francisco, CA — Golden Gate Penthouse** (m/o from Golden Gate, 15 [88])

- 1969-12-17 … Pleasant Hill, CA — Century 21* (13) [unreserved seating]

Note that during the engagement the Warner Hollywood’s name was changed to Hollywood Pacific.

The domestic general release of 2001: A Space Odyssey commenced in autumn 1968 and continued into 1969. Numerous re-releases and countless revival screenings followed.

While not a complete listing, what follows are details of some of the key international roadshow engagements of 2001.

- 1968-04-10 … Tokyo, Japan — Theatre Tokyo* (24)

- 1968-04-11 … Johannesburg, South Africa — Royal*

- 1968-05-01 … London, UK — Casino* (47)

- 1968-05-01 … Sydney, Australia — Plaza* (12)

- 1968-05-02 … Melbourne, Australia — Plaza* (11)

- 1968-07-03 … San Juan, Puerto Rico — Metro**

- 1968-07-04 … Sao Paulo, Brazil — Majestic*

- 1968-07-25 … Dublin, Ireland — Plaza*

- 1968-08-09 … Auckland, New Zealand — Cinerama*

- 1968-08-24 … Vienna, Austria — Gartenbau*

- 1968-08-27 … Stockholm, Sweden — Vinterpalatset*

- 1968-09-02 … Brussels, Belgium — Varietes* (10)

- 1968-09-11 … Munich, West Germany — Royal* (12)

- 1968-09-25 … Zuerich, Switzerland — Apollo*

- 1968-09-27 … Paris, France — Empire* (12) [Version Originale]

- 1968-09-27 … Paris, France — Gaumont Palace* [Version Francaise]

- 1968-10-17 … Barcelona, Spain — Florida*

- 1968-10-31 … Mexico City, Mexico — Cine Latino***** (15)

- 1968-11-07 … Buenos Aires, Argentina — Ideal*

- 1968-12-11 … Milan, Italy — Alcione*

- 1968-12-11 … Rome, Italy — Royal*

- 1968-12-12 … Frankfurt, West Germany — MGM* (10)

THE Q&A

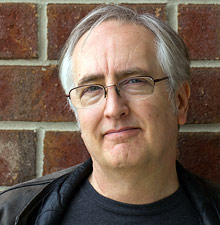

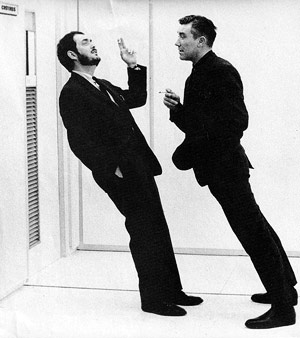

Chris Barsanti is the author of The Sci-Fi Movie Guide: The Universe of Film from Alien to Zardoz (Visible Ink; 2014).

Chris Barsanti is the author of The Sci-Fi Movie Guide: The Universe of Film from Alien to Zardoz (Visible Ink; 2014).

His other books include Filmology: A Movie-a-Day Guide (Adams Media; 2010), Handy New York City Answer Book (Visible Ink; 2017), and (with Brian Cogan and Jeff Massey) Monty Python FAQ: All That’s Left to Know about Spam, Grails, Spam, Nudging, Bruces, and Spam (Applause; 2017).

He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle, Online Film Critics Society and New York Film Critics Online, and has written for Film Journal International, Film Threat and The Hollywood Reporter.

Raymond Benson is a college-level film history instructor (who includes a screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey in his curriculum) and author of three-dozen books.

Raymond Benson is a college-level film history instructor (who includes a screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey in his curriculum) and author of three-dozen books.

He is the third — and first American — continuation author of official James Bond novels.

His new original thriller In the Hush of the Night will be published in May by Skyhorse Publishing.

Peter Krämer is the author and editor of eight academic books, including the BFI Film Classics volume on 2001: A Space Odyssey (published in 2010).

Peter Krämer is the author and editor of eight academic books, including the BFI Film Classics volume on 2001: A Space Odyssey (published in 2010).

He is a Senior Fellow in the School of Art, Media and American Studies at the University of East Anglia in Norwich (UK).

His other books include The New Hollywood: From Bonnie and Clyde to Star Wars (Wallflower, 2006) and American Graffiti: George Lucas, the New Hollywood and the Baby Boom Generation (forthcoming from Routledge).

Lee Pfeiffer is the co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of Cinema Retro magazine, which celebrates films of the 1960s and 1970s and is “the Essential Guide to Cult and Classic Movies.”

He is the author of several books including The Films of Sean Connery (Citadel, 2001) and (with Dave Worrall) The Essential Bond: The Authorized Guide to the World of 007 (Boxtree, 1998/Harper Collins, 1999) and (with Philip Lisa) The Incredible World of 007: An Authorized Celebration of James Bond (Citadel, 1992).

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): How do you think 2001: A Space Odyssey should be remembered on its golden anniversary?

Chris Barsanti: As the first time that science fiction cinema was taken seriously. The genre had taken itself seriously before and was occasionally rewarded for it — all the talk about how Forbidden Planet was inspired by The Tempest, for instance. But it wasn’t until 2001 that the genre came to be seen as a body of work that could be based as much on the wonderment of ideas as on the whiz-bang of special effects and extraterrestrials.

Raymond Benson: 2001: A Space Odyssey is a landmark film that pushed many envelopes and is still today a divisive motion picture. Any work of art that can generate debate and passionate opinions about it after 50 years must be doing something right. I’ve always felt it was much more than just “a movie.” Stanley Kubrick got us to examine and appreciate the mystery of the universe and our place in it, and he got us to ask questions about the meaning of life, our past, and our future. Heady stuff, both profound and daring for a Hollywood “mainstream” big-budget motion picture. As one critic put it, Kubrick made the most expensive “art house movie” ever.

Peter Krämer: As one of the greatest movies of all time. As a key source for much of the science fiction cinema of recent decades, from Star Wars to Avatar and beyond. As a film that has dazzled and inspired people for many years.

Peter Krämer: As one of the greatest movies of all time. As a key source for much of the science fiction cinema of recent decades, from Star Wars to Avatar and beyond. As a film that has dazzled and inspired people for many years.

At the same time, we should not forget that upon its initial release 50 years ago, the film reached out to, and found, a huge audience in the United States. Many people, including many film scholars, think that the film was initially rejected both by critics and by cinemagoers and only belatedly found an audience, largely composed of young people, many of which are said to have watched the film under the influence of mind-altering substances.

When I carefully examined reports in the film industry trade press, box office figures and the many letters that cinemagoers wrote to Stanley Kubrick after seeing his film, I had to conclude that in fact 2001 was a massive success from the outset, not only with countercultural youth, but also, for example, with young children and their parents.

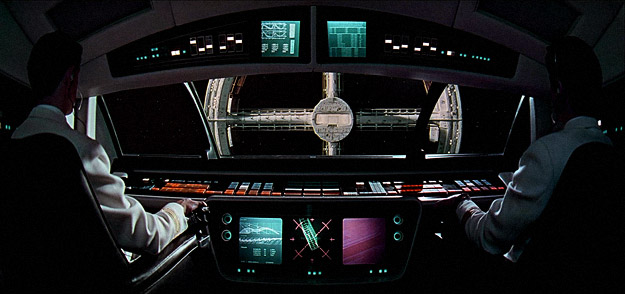

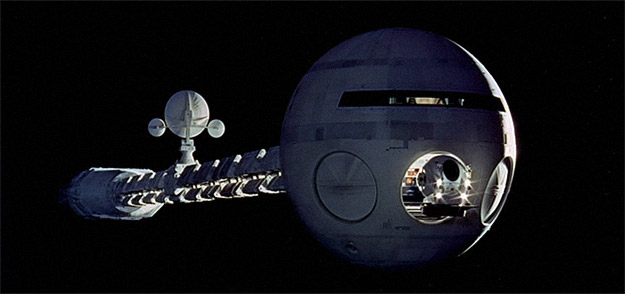

We also have to remember that in the United States the film was first presented as a so-called roadshow, which meant that it was initially shown, at raised ticket prices, in only very few cinemas, most of them Cinerama theaters with their huge curved screens; the show began with an overture and included an intermission. This way of presenting a film was typical for Hollywood’s biggest productions, and it actually was a special occasion for all those people who had lost their cinema going habit to return to the big screen. This film was really meant for everyone!

Finally, going against all those critics who understand the film as being infused with Kubrick’s characteristic pessimism, we should really remember it as a statement of hope. Kubrick made 2001 in response to the utterly devastating conclusion of his previous film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb from 1964; this film ends with the explosion of a nuclear “doomsday device” which will bring an end to all human life on the surface of the Earth.

My research in the Stanley Kubrick Archive at the University of the Arts London strongly suggests that Kubrick intended 2001 to offer an optimistic vision of the future to counter the deep pessimism of Dr. Strangelove. And that’s exactly how many people writing to Kubrick about their experiences with the film understood it. It gave them hope about their own future, their ability to change, to renew themselves, and about the future of humanity as a whole. We should remember 2001 as a hopeful vision of boundless human potential.

Lee Pfeiffer: 2001 is innovative, inspired filmmaking at its zenith. Kubrick wanted to make the most unique, intelligent take on the science fiction genre and he truly succeeded. It’s easy to see why the movie initially alienated audiences that were probably expecting another film about little green men with ray guns. What they got was something that made them think. For that reason, the movie wasn’t shaping up as a major hit until young people discovered it and relished the technical aspects of it. The film fit right in with the hippie drug culture of the late 1960s. I’d like to think many of the people who made the film a major success were actually looking beyond the apparent achievement in special effects and tried to diagnose what it was all about. The beauty of 2001 is that there are no easy answers. It parallels Patrick McGoohan’s classic TV series The Prisoner, which was telecast a year earlier, in that the answers lie in the mind of the individual viewer, thus it can mean completely different things to different people. I’m not sure what the hell it’s all about, either...but it’s a fascinating experience each time I see it. The effects were state-of-the-art in 1968 and are even more impressive today. We live in an era in which effects can be generated on computers, whereas Kubrick and his team achieved everything the old-fashioned way — and it’s never been equaled.

Coate: What did you think of 2001 when you (first) saw it?

Barsanti: I can’t [recall when I first saw it]. Like other big-screen classics of the 1950s and ’60s like Dr. Strangelove or Bridge on the River Kwai, to me, 2001 was just always part of my movie consciousness. I was definitely very young when I first saw it, which is not a bad thing. While the movie is devilishly complex in some of its thinking, it’s also incredibly simple: Aliens come to earth and help humans evolve. Later, humans go to space and get a little ahead of themselves. They meet an alien — or aliens. Cue lightshow. Even a five-year-old gets that. Also, the scene of the primate hurling the bone into the sky and having it return as a spacecraft was probably my first awareness of what editing could do.

Benson: I saw it on first release in Odessa, Texas, with my father, in 70mm. I was 13 years old. I already loved movies and was just beginning to have an appreciation for the many aspects that went into the making of a film — not just whether or not it entertained me. I believe that 2001 gave me a better understanding of what “Directed By” means. From that point on, I became interested in who Stanley Kubrick was. As I grew older, I sought out his earlier films and kept up with his career until the end. Curiously, when I first saw 2001, I had no problem “getting” it. As we were leaving the theater, my father asked me if I understood the movie — he hadn’t, although he found it amazing and was entranced by the picture all the way through. I explained my interpretation to him, and he was impressed. During that first release, all my friends my age “didn’t understand it,” but they all liked it. It was too much of a never-before-seen cinematic experience not to like.

Benson: I saw it on first release in Odessa, Texas, with my father, in 70mm. I was 13 years old. I already loved movies and was just beginning to have an appreciation for the many aspects that went into the making of a film — not just whether or not it entertained me. I believe that 2001 gave me a better understanding of what “Directed By” means. From that point on, I became interested in who Stanley Kubrick was. As I grew older, I sought out his earlier films and kept up with his career until the end. Curiously, when I first saw 2001, I had no problem “getting” it. As we were leaving the theater, my father asked me if I understood the movie — he hadn’t, although he found it amazing and was entranced by the picture all the way through. I explained my interpretation to him, and he was impressed. During that first release, all my friends my age “didn’t understand it,” but they all liked it. It was too much of a never-before-seen cinematic experience not to like.

Krämer: I first saw 2001 as a teenager at a small-town cinema in Germany in the late 1970s. I really did not know what to make of it, although I had already long been a science fiction fan, mostly of novels, though, not of films. I was strangely moved, and, I think for the first time in my life, I went back to the cinema to see the same film again. I also read Arthur C. Clarke’s novel, which explained everything that was going on in the film. But somehow these explanations weren’t very satisfactory. The mysteries of the film were more interesting and engaging when left unexplained.

The whole experience was so unusual for me that I started to think more seriously about films. Round about the same time I also watched Kubrick’s next film, A Clockwork Orange, which blew me away, but also unsettled me. Together, these two cinema experiences are probably the main reason why I eventually decided to study film and become a film scholar.

Coate: In what way is 2001 a significant motion picture?

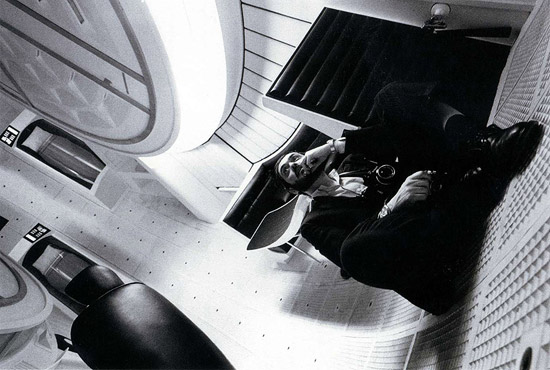

Benson: As has often been said, Kubrick set out to make a non-verbal, visual experience that would fill an audience with awe. He experimented with the narrative structure and told the basic story in strictly visual terms — which people in 1968 were not really used to since silent films ended in the late 1920s. The dialogue in the movie barely informs on the story. It’s all visual clues that tell us what’s going on. Add to that the technical perfection that Kubrick brought to the production...nothing like it had been done before. With his obsession for scientific accuracy, the ground-breaking visual effects work, the use of classical music as a soundtrack that previously really hadn’t been utilized in this way, the courageous use of sound (or silence) in the space sequences, and the existential themes inherent in the story — 2001 is truly one of the most outstanding achievements in cinema history.

Coate: In what way was Stanley Kubrick an ideal choice to direct 2001 and where does the film rank among his body of work?

Barsanti: Kubrick is probably the only director at that time who was comfortable with trimming away all the extraneous plotting that other filmmakers would have tagged on to this journey. He was after spectacle and discovery and expansion of consciousness: some subplot about the broken family Dave had left behind on Earth would have just cluttered things up. In terms of his body of work, 2001 is the last great thing Kubrick achieved. After this, his body of work became increasingly self-indulgent and dry, without the dark wit and sparkle of his earlier movies and little of 2001’s visual and philosophical grandeur.

Benson: I believe 2001 is Kubrick’s crowning achievement. It’s the movie that launched him into “superstar” status that placed him alongside the likes of Welles, Bergman, Fellini, Kurosawa, Hitchcock, Ford... I can’t imagine anyone else directing the film or even conceiving of it, for the picture is full of many of Kubrick’s thematic signatures — man’s inhumanity to man, the flaws of being human, how technology can be a danger — but I also think he uses these themes, at the end of the picture, in an optimistic way. There is hope for mankind in the final image of the Star-Child. Man will evolve into something greater. Someday. Maybe.

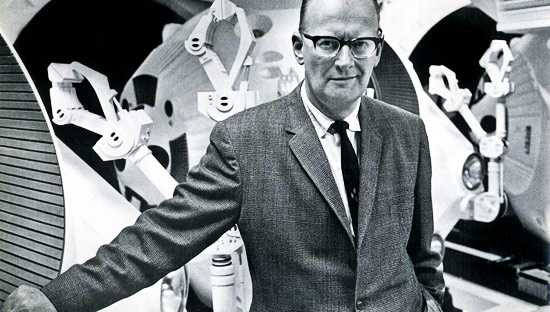

Krämer: I don’t think one can say that Kubrick was “chosen” to direct 2001. He developed the whole project from scratch. Soon after the release of Dr. Strangelove, he contacted Arthur C. Clarke, one of the world’s leading science fiction writers and also the author of many popular science books, and asked him whether he wanted to collaborate on developing a story for a science fiction film which would center on humanity’s encounter with an extraterrestrial civilization.

Krämer: I don’t think one can say that Kubrick was “chosen” to direct 2001. He developed the whole project from scratch. Soon after the release of Dr. Strangelove, he contacted Arthur C. Clarke, one of the world’s leading science fiction writers and also the author of many popular science books, and asked him whether he wanted to collaborate on developing a story for a science fiction film which would center on humanity’s encounter with an extraterrestrial civilization.

As is evidenced by many public and private statements, Kubrick was deeply convinced that humanity was very likely to destroy itself in an all-encompassing nuclear war in the not too distant future, and in Dr. Strangelove he had shown how this might happen. But he also felt that there was a slim chance that humanity might be transformed and avoid this terrible fate.

Well, if you are convinced that humanity will destroy itself on Earth, where do you look for an alternative? To heaven, of course. If you are religious, you might hope for God’s intervention. If not (and neither Kubrick nor Clarke were religious), you hope for an encounter with something transformative in space, or perhaps you hope that simply going into space might give humanity a new perspective and thus transform it. That was, I am convinced, the main driving force behind the making of 2001.

It is also the case that only Kubrick would have been able to make a film like this at this point in time. This was a big budget movie from the outset, and it nominally belonged to a genre — science fiction — which, with very few exceptions, had never done particularly well at the box office. But Kubrick had an excellent commercial track record; his last three films — Dr. Strangelove, Lolita and Spartacus — had all been hits, and he was also already widely regarded as one of the greatest American filmmakers. So he managed to get MGM to finance what was initially called Journey Beyond the Stars. And then he took much, much longer than expected and went massively over budget. But in the light of Kubrick’s reputation and track record, the studio did not interfere.

And then he did something so amazing that even today I completely baffled. For several years, 2001 was meant to have had a prologue showing interviews with scientists talking about topics important for understanding the film, a voiceover narration which explained and commented on what was happening in the story, long dialogue sequences which did the same, and a conventional score. But not long before the film’s release in April 1968, Kubrick, one after the other, removed all these elements. He thought that the film would work better if it was just as mysterious as the monoliths at the center of its story (and the pre-recorded music he used, especially Ligeti’s eerie compositions, really helped to create this mystery, already starting with the overture).

It is truly astonishing that even at this point MGM didn’t interfere to protect the huge investment the studio had made. But either the top executives trusted Kubrick’s judgment that this mysterious film would work with a mass audience, or they were simply too caught up in internal power struggles to have much time for 2001. As it turned out, Kubrick was right. 2001 became one of the highest grossing films of all time in the United States.

Pfeiffer: Some years ago, I was writing and co-producing a documentary for Sony about the making of Dr. Strangelove. Among the people we interviewed was Roger Caras, a former executive in publicity for Columbia Pictures. Kubrick had been impressed with the offbeat ad campaign Roger had overseen for Strangelove, a minimalist cartoon that depicted the U.S President and Soviet Premier both on the Hot Line. Shortly thereafter, Kubrick took Roger to lunch at Trader Vic’s in New York City, ostensibly for lunch. However, he had another purpose. He informed Roger that his next film would be his most ambitious and would involve space travel and have a very existential aspect to it. Roger very much respected Kubrick’s instincts and listened intently as Kubrick outlined the bare-bones scenario for what would become 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick explained that he didn’t want this to be some kind of sci-fi thriller, but the most intelligent examination of the space age ever undertaken. Furthermore, his original concept (dropped from the finished film) would center on the first meeting between human beings and aliens. Roger said that Kubrick drew some rough “stick man”-like figures on the back of a Trader Vic’s napkin to illustrate the fact that the aliens would be much taller than a human being.

As the conversation continued, Kubrick shocked Roger by imploring him to quit his executive position at Columbia to work full time on the space film project, which was untitled at that time (this was 1964). Kubrick assured him that it would take years from concept to completion. He also said he wanted Roger to fly to different nations to interview prominent scientists for a prologue he intended to use in the finished film. It was important to Kubrick that the movie had gravitas and be grounded in realistic scientific concepts. Roger came home and informed his shocked wife that he was indeed going to quit his job and work with Kubrick. His rationale: Kubrick was the only true genius he had ever known. Not just a filmmaking genius, but a genuine genius who was conversant in virtually every subject. Roger had been friendly with the writer Arthur C. Clarke, who lived in Ceylon. He told Kubrick to read his works and Kubrick did just that. He was impressed by a story Clark had written, The Sentinel and contacted the author about the possibility of using it as an inspiration for his space film. Clarke was so enthused about the project that he agreed to co-author the screenplay with Kubrick. The rest, as they say, is history. The interviews with scientists that Roger had so painstakingly completed were also cut before the release print was finalized because a screening with MGM executives resulted in the feeling that it got the movie off to a slow and turgid start. An interesting side note: when our interview with Roger Caras was complete, he went into one of his files and said he would show us something priceless. He removed the original Trader Vic’s cocktail napkins that Kubrick had doodled his concepts on. When I asked him what possessed him to keep them at the time, he said that anything in writing from Kubrick had potential historical value. He was right.

Roger Caras disputed the popular legend that Stanley Kubrick was a recluse. He acknowledged he had eccentricities but was not insulated from the world. Kubrick filmed Dr. Strangelove in England and became enamored of the UK. He would only leave the UK one more time, when he had to show the original cut of 2001 to MGM executives in America. Kubrick, a former pilot, had experienced a near-death trauma when flying his private plane. He never flew again. Roger said that for reasons Kubrick never explained, he would not travel above 30 mph in any vehicle, which made accompanying him on the road an exasperating experience. Aside from these quirks, however, Roger said Kubrick enjoyed being in a group of intelligent, eclectic people and occasionally hosted parties at his estate. Roger said it was sheer bliss seeing legends from the worlds of politics, art, cinema and literature all meeting and engaging in conversation.

Coate: How would you describe 2001 to someone who has never seen it?

Benson: Since I screen it for young college-age film students, many have not seen it. I warn them that it is meticulously-paced, and that they will most likely find parts of it to be slow. I preface this with the fact that movies moved much slower prior to the 1980s and the advent of MTV. I explain that this has a hypnotic effect for audiences who accept the pace for what it is, settle into it, and let the movie envelop them. I then go on to say it is considered by many (including the AFI) to be the #1 science fiction film of all time, and how it leaves the audience to interpret it as they choose. Usually students are more receptive to it after a proper introduction that places the film within the context of when it was released.

Krämer: I think that today people are likely to have all kinds of preconceptions before they watch 2001, mainly to do with its status as a masterpiece and also perhaps as an expression of Kubrick’s pessimism. I wish that people could just drop these preconceptions, and approach the film as if they were going on a journey, a journey into the unknown. After all, the film has “odyssey” in its title.

One has to expect to get lost for a while on this odyssey, but one can also be certain to be returned home safely. It is best to experience each stage of the journey in its own right, because there are so many sounds and images, actions and motifs to contemplate. Perhaps one can use the intermission (which appears on most DVD and Blu-ray editions) to actually take a break and think about what one has seen and heard, and how the preceding stages of the journey relate to each other, and where the journey might go next.

At the end of the film, it is only fitting if one allows oneself to be haunted by the final image of the Star-Child looking directly at the camera and thus at the audience. One can explore how this image relates to the title shown right after the opening credit sequence: The Dawn of Man. What does all this tell us about what it means to be human? And about human history?

So my best advice would be to keep an open mind when watching 2001, to try to experience everything it has to offer, and to go away from it with many questions rather than with simple answers.

Coate: Any thoughts on the film’s sequel?

Krämer: I actually like 2010 quite a lot. The only problem is that it is pales in comparison with Kubrick’s film. It is difficult to watch it without constantly comparing it with 2001, and it is diminished by this comparison. Otherwise it is a perfectly engaging and stimulating film. I have read all the sequel novels that Clarke wrote and also the “time odyssey” novels he wrote together with Stephen Baxter. There are some wonderful ideas here, but, again, nothing quite lives up to the magical experience of watching Kubrick’s film.

Coate: Has 2001 been well-served on its numerous home-video releases? Is it worth watching in the home?

Benson: It’s made to be seen on the big screen — the bigger the better — and with a good sound system. Kubrick wanted the film to overwhelm an audience. Back in the 1980s, 2001 was the first VHS tape I bought, and I really hated the pan-and-scan version. A widescreen version came out a little later, and that helped, but it was no substitute for the big screen. DVD improved this, and then we got flat screen, widescreen televisions and Blu-ray. This helped immensely. I believe that if you have a really good home theater setup with a big TV screen, sound, and Blu-ray, in a darkened room with no distractions, you can recreate a decent experience watching the film (or any film, for that matter!).

Krämer: In my experience of watching 2001 dozens of times, it works on small screens as well as on big ones. Of course, it is a very special treat to see the film on a huge screen, perhaps even on an old Cinerama screen (as I once did in Bradford in the UK). But one can also immerse oneself when watching it on a television set, especially if it is large one with good sound. I think watching it while being alone may actually add something to the experience, especially when one is confronted with the Star-Child at the end. I have to admit that I never tried to watch it on a tablet or a smart phone. I wonder what that would be like.

Coate: What is the legacy of 2001?

Benson: As said above — it remains the #1 science fiction movie of all time. For me personally it’s the #1 movie of all time because it quite frankly changed my life. I had loved motion pictures prior to 2001, but after it I became seriously interested in the craft and history of cinema. I’ve seen it maybe a hundred times, and I continue to find new things to admire. It will always inspire and move me.

Krämer: The legacy of 2001 is difficult to map, because so many people were deeply affected by this film. Some, such as myself, became film scholars. More importantly, others, such as James Cameron, became film makers (in fact I am a great admirer of Cameron’s work, and I think that Avatar is the most powerful reworking of 2001 that we have seen in a long time). There are also no doubt many people who were inspired to get into space exploration and SETI (the search for extraterrestrial intelligence) or artificial intelligence research. Judging by the letters from cinemagoers Kubrick received, numerous people also simply felt that their lives did not have to go on as before, that change was possible, that everything was possible. Who knows what they eventually did with this feeling!?

Pfeiffer: The legacy of 2001 is apparent in the fact you are doing a major article about it 50 years later. Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke strove to challenge people’s imaginations and they succeeded. There are so many landmark visuals in the film, we can’t recount them here. It’s been criticized for being a cold, antiseptic film when it comes to exploring the human condition — and it is indeed that. However, Kubrick wasn’t interested in the viewers getting under the skins of the characters. If he was, he would have cast big box office names in the lead roles. Instead, he wanted to create a film that had a legacy that would last for many years and he certainly succeeded in that. The film inspired a new generation of filmmakers and continues to do so today. Doubtless, it will continue to do so even 50 years from now.

Coate: Thank you — Chris, Raymond, Peter, and Lee — for sharing your thoughts about Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey on the occasion of its 50th anniversary.

--END--

IMAGES

Selected images copyright/courtesy Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, MGM/UA Home Entertainment, Stanley Kubrick Productions, Warner Home Video. 70mm frames scanned by Schauburg Archive. Home-video collage by Cliff Stephenson. Roadshow ticket stub from the collection of Robert Morrow. Raymond Benson photo by Katherine Tootelian.

SOURCES/REFERENCES

The primary references for this project were regional newspaper coverage and trade reports published in Billboard, Boxoffice, The Hollywood Reporter and Variety. All figures and data included in this article pertain to the United States and Canada except where stated otherwise. This work is based upon articles by same author previously published at In70mm.com and CinemaTreasures.org.

SPECIAL THANKS

Al Alvarez, Jim Barg, Chris Barsanti, Don Beelik, Raymond Benson, Kirk Besse, Herbert Born, Serge Bosschaerts, Raymond Caple, Miguel Carrara, Evans A. Criswell, Nick DiMaggio, Carlos Fresnedo, Sheldon Hall, Thomas Hauerslev, William Hooper, Bill Huelbig, Mark Huffstetler, Peter Krämer, Bill Kretzel, David Larson, Ronald A. Lee, Mark Lensenmayer, Paul Linfesty, Stan Malone, Robert Morrow, Gabriel Neeb, Jim Perry, Lee Pfeiffer, Richard Ravalli, Jochen Rudschies, Sam Shapiro, Grant Smith, Cliff Stephenson, Bob Throop, Joel Weide, and Vince Young, and an extra special thank-you to all of the librarians who helped with this project.

IN MEMORIAM

- H.L. Bird (Sound Mixer), 1909-1968

- A.W. Watkins (Sound Supervisor), 1895-1970

- Geoffrey Unsworth (Director of Photography), 1914-1978

- James Liggat (Casting), 1920-1981

- Wally Veevers (Special Photographic Effects Supervisor), 1917-1983

- Leonard Rossiter (“Dr. Andrei Smyslov”), 1926-1984

- Sean Sullivan (“Dr. Bill Michaels”), 1921-1985

- Tom Howard (Special Photographic Effects Supervisor), 1910-1985

- John Alcott (Additional Photography), 1931-1986

- Alan Gifford (“Poole’s Father”), 1911-1989

- Tony Masters (Production Designer), 1919-1990

- Ernest Archer (Production Designer), 1910-1990

- Robert Beatty (“Dr. Ralph Halvorsen”), 1909-1992

- William Sylvester (“Dr. Haywood R. Floyd”), 1922-1995

- John Hoesli (Art Director), 1919-1997

- Frank Miller (“Mission Controller – Voice”), 1944-1998

- Stanley Kubrick (Writer-Producer-Director-Special Effects Designer/Director), 1928-1999

- Winston Ryder (Sound Editor), 1915-1999

- Ray Lovejoy (Editor), 1939-2001

- Edward Bishop (“Aries-1B Lunar Shuttle Captain”), 1932-2005

- Arthur C. Clarke (Writer), 1917-2008

- Harry Lange (Production Designer), 1930-2008

- Margaret Tyzack (“Elena”), 1931-2011

- Bill Weston (“Astronaut”), 1941-2012

- Stuart Freeborn (Makeup), 1914-2013

- Frederick I. Ordway III (Scientific and Technical Consultant), 1927-2014

- Ann Gillis (“Poole’s Mother”), 1927-2018

-Michael Coate

Michael Coate can be reached via e-mail through this link. (You can also follow Michael on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook)