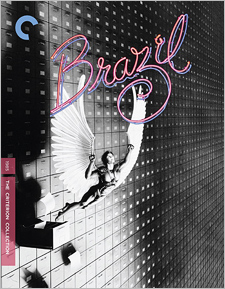

Brazil (4K UHD Review)

Director

Terry GilliamRelease Date(s)

1985 (June 3, 2025)Studio(s)

Universal Pictures (The Criterion Collection – Spine #51)- Film/Program Grade: A+

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: B+

- Extras Grade: A

Review

The torturous post-production process for Terry Gilliam’s Brazil was so rancorous that critic Jack Mathews called it The Battle of Brazil in his 1987 book chronicling the route that the film took to reach the screen, in one form or another, by any means necessary. Like any battle, lines were drawn in the sand between the opposing sides, and while there may have ultimately been (relatively) clear winners and losers, there weren’t necessarily unambiguous heroes and villains. Oh, Universal Pictures President and CEO Sid Sheinberg filled the latter role adequately enough, and there was something of a white knight that rode in to save the day. Yet however much that Gilliam has portrayed himself as being the hapless victim of studio malfeasance, the reality is that he’s usually made the beds that he’s ended up having to lie in, and he’s been partly to blame for much of the corporate resistance that he’s received. The saga of Brazil was never quite the clear-cut “art vs. commerce” battle that he has portrayed it as being. He still came out more or less on top, although the experience left him with lifelong scars (and he didn’t really learn anything from the experience, as the behind-the-scenes chaos of his next film The Adventures of Baron Munchausen proved).

As with many wars, the roots of the battle over Brazil were established years earlier. Gilliam first conceived of the story during his Monty Python days (his Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life prologue The Crimson Permanent Assurance ended up serving as something of a test bed for concepts that he had already been refining for a few years). He finished a first draft of the screenplay back in 1979 with the help of his Jabbberwocky co-screenwriter Charles Alverson, but the story didn’t really take shape (or as much shape as it ever would, anyway) until playwright Tom Stoppard took a pass at it. Yet the inherently visceral Gilliam wasn’t completely satisfied with Stoppard’s more intellectual approach, so he brought in his friend Charles McKeown to punch things up a bit. Gilliam eventually hooked up with maverick producer Arnon Milchan, who signed onto the project and started an improbable bidding war at the Cannes Film Festival in 1983. The irony was that this particular war was between two studios that had previously passed on the project, Universal and 20th Century Fox, and it would end up being the opening salvo in a conflict involving Gilliam that would take the next two years to resolve, with both studios having a hand in it.

Brazil was inspired by George Orwell’s 1984, although Gilliam has openly admitted that he never actually read the book or even saw any adaptations of it. It’s a unique vision of a dystopian future, or to be more precise, more of a steampunk retro-future. In other words, it’s a riff on 1984 set in a nebulous futuristic time period, looking as if it may have been imagined by someone still living in 1954. In this world, an authoritarian bureaucracy has seized firm control of society, partly by stoking fears of unnamed and unseen terrorists who are supposedly responsible for explosions all over the city. Of course, the real source of the chaos is something far more mundane (it’s not terrorism, but rather simple incompetence), but this particular authoritarian regime isn’t about to let a good crisis go to waste, and it’s the little people like Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) who are caught in the middle.

Lowry is a low-level bureaucrat who is content to work a dead-end job at the Ministry of Information under the less than watchful eye of Mr. Kurtzmann (Ian Holm)—which is much to the consternation of his influential mother Ida (Katherine Helmond), who wants his career to advance. Content or not, Sam still dreams of escaping his mundane existence, imaging a world where he’s a winged hero in search of the woman of his dreams (Kim Greist). In reality, he’s caught in a bureaucratic conflict of his own between the nationalized Central Services and the renegade HVAC technician Harry Tuttle (Robert De Niro). The government is after Tuttle, but when a warrant is misprinted and Information Retrieval accidentally arrests Archibald Buttle (Brian Miller) instead, that one-letter snafu sets off a chain reaction that ends up pitting Sam against his mother, his only friend Jack Lint (Michael Palin), the Deputy Minister of Information Mr. Helpmann (Peter Vaughan), and the entire bureaucratic machine. Yet has he really found the woman of his dreams in the form of Buttle’s upstairs neighbor Jill Layton (Greist), and can they really escape this dystopian nightmare? Brazil also stars Bob Hoskins, Ian Richardson, Jim Broadbent, Sheila Reid, Derrick O’Connor, Ray Cooper, Simon Jones, and Jack Purvis.

As that description should make clear, George Orwell wasn’t the only inspiration for Brazil; another one was Gilliam himself, or rather his 1981 sleeper hit Time Bandits. It really wasn’t authoritarianism per se that interested him as much as it was the tendency for entrenched systems to punish those who dared to dream, an idea that he had already explored in Time Bandits. Yet whether its Kevin, Sam Lowry, or Hieronymus Karl Friedrich von Münchhausen, Gilliam’s own persecution complex clearly informed the stories that he told during that period. Visionary dreamers like these inevitably ended up having to do battle with the forces of evil, aka anyone who insisted on trying to bring them back to the ground. (Even Archibald “Harry” Tuttle’s stubborn insistence on independence was something that had personal appeal for the director.) It wasn’t much of a leap from having these fictional heroes fighting to retain their unique visions of the world to the real-world Gilliam fighting to retain his own vision for Brazil. It all became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Brazil had been greenlit on a $15 million dollar budget, with Universal contributing $9 million for domestic distribution and Fox adding in the balance for international rights. Commendably, Gilliam brought in the ambitious production for slightly less than that figure (although what happened to the surplus became a point of contention between him and Milchan). The real sticking point was the length. He retained final cut, but he was contractually obligated to deliver a film that was under 125 minutes long. His final(?) cut ended up being 142 minutes instead, and he refused to budge. While Fox was content to release that version in Europe in early 1985, Universal drew a line in the sand and dared Gilliam to cross it, knowing full well that they held all the cards. The film had tested poorly, both with test audiences and with the Universal executives themselves, especially Sid Sheinberg. Improbably, he saw Brazil as a film with commercial appeal, as long as it was cut down to considerably less than 125 minutes and given a happy ending. And unbeknownst to Gilliam, Sheinberg had his own team of editors working to do just that. Meanwhile, Gilliam did cut the film down to 132 minutes and incorporated a couple of changes at Sheinberg’s suggestion, but that wasn’t good enough.

Universal’s intransigence ended up pushing Gilliam out of Sam Lowry territory and into full-on Harry Tuttle mode. He went rogue, arranging screenings of his cut wherever possible, which quickly brought him into conflict with Universal’s legal department. He also took out a full-page ad in Variety with a simple block of text in the middle reading “Dear Sid Sheinberg: When are you going to release my film Brazil?” (There’s no bridge so inflammable that Gilliam wouldn’t gleefully take a torch to it anyway.) The tipping point came when he screened the film for the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and they ended up being the knight in shining armor that rode a white horse across the battle lines and finally brought the conflict to an end. They named Brazil the Best Picture of 1985, Gilliam as Best Director, and also awarded the screenplay. That forced Universal’s hand, and they finally released Brazil in December of that year (albeit in the slightly shortened 132-minute version), with little fanfare and minimal box office returns. (Sheinberg’s cut ended up relegated to syndicated television instead.)

The reality is that there was never going to be a happy ending for Brazil, at least in terms of box office, regardless of how the film itself ended. It’s a bleak vision of a dystopian future that was always going to be a hard sell in any era, let alone in Ronald Reagan’s America. It was all there in the script (the ending included), so the studio executives had no one to blame but themselves (although Gilliam’s abrasive personality gave them an easy scapegoat). And Gilliam did agree to deliver a final cut under 125 minutes, so he also has no one to blame but himself for failing to do so. The reality is that artists who take other people’s money are beholden to those who pony up the funds—the movie business is neither pure art nor pure commerce, but rather a blend of the two. Universal did lose money on Brazil, but they ended up with one of the best films of the entire decade in their catalogue, and that’s no small thing. In the battle of Brazil, the real winner was posterity, and the myriad fans who have always recognized it as a visionary masterpiece in any of its forms—well, Sid Sheinberg’s version excepted.

Speaking of Sheinberg, it’s worth pointing out that while his notorious “Love Conquers All” recut of Brazil is a complete disaster, the lines between Gilliam’s original 142-minute cut and the 132-minute American theatrical version aren’t quite so clear (and they’re even muddier when you consider the slightly different 142-minute director’s cut version that The Criterion Collection released on home video). There are some minor deletions in the American version (like references to Father Christmas) that don’t have much of an impact one way or the other, but it also restores Tom Stoppard’s “My God, it works!” punchline at the end of the first plastic surgery sequence (according to Stoppard, Gilliam cut it from the European version because he just didn’t get the joke). The lengthiest deletion is the processing scene after Sam’s arrest, including a re-appearance by Mr. Helpmann as Father Christmas. While it does provide some extra texture that helps to flesh out this bureaucratic nightmare, it also bogs down the narrative momentum at a crucial moment, and Mr. Helpmann has a line of dialogue that gives away the game with the film’s ending far too early. The American version utilizes a shock cut from the restraints being put over Sam’s head to them being pulled off again in the torture chamber, and frankly, the film as a whole is far more effective that way.

Yet the single most impactful difference doesn’t even affect the running time at all. Both versions end with Sam on the platform inside the torture chamber as the credits roll, but at Sheinberg’s suggestion, the American version fades in the sky over the background walls, leaving Sam floating in a sea of clouds. To be fair, Gilliam had originally scripted it that way, but he decided to leave things looking bleaker in the European version. Yet in this case, Sheinberg was right. It brings everything full circle with the clouds at the beginning of the film, and it correctly indicates Sam’s mental state at that point. (It’s also more in tune with Michael Kamen’s exuberant closing credit version of Ary Barroso’s Aquarela do Brasil.) The system may have taken Sam’s body, but they can’t have his soul. Gilliam has described his ending of Brazil as being a “happy” one for precisely that reason: this visionary dreamer has been left alone with his dreams, and what could make a person happier? So, Sheinberg’s clouds are really in keeping with Gilliam’s original intent, and it’s a shame that the director chose to omit them once again for his final cut on home video. Not all compromises are bad ones.

Cinematographer Roger Pratt shot Brazil on 35mm film using J-D-C cameras with spherical lenses, framed at 1.85:1 for its theatrical release. This version is based on a 4K scan of the original camera negative, which was cut to conform to the U.S. theatrical version, so a 35mm internegative was used for the missing scenes from the European version. Digital restoration work was done at Prasad Corporation in Burbank, while grading was handled at Company 3 in London (both Dolby Vision and HDR10 grades are included on the disc). It’s a marked improvement over Criterion’s previous version, which was based on a 2K scan of an interpositive. Fine details are much better resolved, as is the grain (although the encode still struggles with it at a few points, especially where fog and/or steam are concerned). The colors are also noticeably richer, with none of the flat telecine look of the previous version, but they never appear oversaturated, either. It’s like a veil has been lifted—clarity has been improved across the board. The added footage blends in fairly seamlessly, and there’s noteworthy damage there or anywhere else. It’s not quite perfect, but it’s damned close, and it’s the best that Brazil has ever looked, successfully translating everything to 4K video while still retaining a natural filmic appearance.

Audio is offered in English DTS-HD Master Audio, with optional English SDH subtitles. Brazil was released in Dolby Stereo, so it’s a four-channel surround mix, and kudos to Criterion for continuing to point out that fact in their booklet, and reminding viewers to engage the decoder on their receiver or processor. This version was derived from the 35mm Dolby Stereo magnetic tracks, with digital tools used in order to eliminate any tape hiss, crackling, or other defects. Everything sounds clean, clear, and dynamic for a Dolby Stereo mix of this vintage, with surround engagement whenever appropriate, and an emphasis on the front channels whenever it’s not. In other words, it’s not necessarily fully immersive, but it’s good enough for this kind of film. Michael Kamen’s score and the various versions of Aquarela do Brasil are front and center, as they should be, and they’re just as responsible for driving Brazil as any of Gilliam’s visuals are.

Criterion’s 4K Ultra HD release of Brazil is a three-disc set that includes two Blu-rays, one with a 1080p copy of the film, and the other with the “Love Conquers All” version of the film and the bulk of the extras. Note that the Blu-ray discs are both repressings from Criterion’s 2012 release of Brazil, so they’re not remastered versions (and thus the feature film is still reframed at 1.78:1). The artwork is also identical, so only the details on the back and the thickness of the Amaray case serves as a clue that this is the 4K version (even the spine numbers are the same). While the booklet has been reconfigured slightly (it’s 18 pages now instead of 20), it still contains the same essay by David Sterritt, although the restoration notes have been updated. The following archival extras are included:

DISCS ONE & TWO: FEATURE FILM (UHD & BD)

- Audio Commentary by Terry Gilliam

Criterion has a long history with Brazil, and the commentary with Terry Gilliam was recorded for their CAV LaserDisc boxed set back in 1996. That was barely a decade after the battles of Brazil, so the wounds were still fresh, and he doesn’t hold back. He describes the evolution of the story across the various drafts, including the influence that Tom Stoppard had on the script—Gilliam notes that Stoppard had a gift for words as opposed to his own gift with visuals, and Stoppard is the one who conceived of the Tuttle/Buttle confusion that held the entire story together. (Stoppard was also responsible for wordplay like the anagram that provides a vital clue for Sam Lowry.) Gilliam is indeed fascinated with visuals, so he goes into great detail describing the production design, costumes, special effects, and cinematography. Yet he does delve into thematic details as well, and offers plenty of praise for what the actors brought to the table. Gilliam also notes some of the changes in the various versions, while he glosses over others. He refers to the Criterion cut as being his “fifth and final version,” noting some things that he had cut at the last minute (on the physical prints themselves) for the European version, which were reinstated for home video. He acknowledges that he had a hard time deciding between the clouds over the credits in the American version and the plain silo in the European version, but he also confirms that it’s a happy ending since Sam has won in the end, free in his own mind.

DISC THREE: EXTRAS (BD)

- What Is Brazil? (Upscaled SD – 29:07)

- The Production Notebook:

- We’re All in It Together: The Brazil Screenwriters (Upscaled SD – 10:42)

- Dreams Unfulfilled: Unfilmed Brazil Storyboards:

- Introduction (HD – :59)

- The Eyeballs (HD – 2:50)

- The Storeroom of Knowledge (HD – 3:21)

- The Cages (HD – 4:23)

- The Stone Ship (HD – 2:47)

- The Fall (HD – 1:07)

- The Samurai (HD – 2:07)

- The Sky Cube (HD – 2:00)

- The Forces of Darkness (HD – 1:33)

- Designing Brazil (HD – 20:45)

- Flights of Fantasy: Brazil’s Special Effects (HD – 9:50)

- Fashion and Fascism: James Acheson on Brazil’s Costume Design (HD – 9:41)

- Brazil’s Score (Upscaled SD – 9:41)

- The Battle of Brazil: A Video History (Upscaled SD – 55:09)

- Brazil: The “Love Conquers All” Version (Upscaled SD – 93:44)

- Trailer (Upscaled SD – 2:36)

The remaining extras were also culled from Criterion’s original LaserDisc release, although some of them have received visual upgrades. What Is Brazil? is a featurette that was filmed by Rob Heddon (yes, that Rob Heddon, director of Friday the 13th Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan) on the set of Brazil. That means it’s not a complete making-of documentary, but that fact makes it even more interesting in hindsight. It includes interviews with Gilliam, Jonathan Pryce, Michael Palin, Robert De Niro, Katherine Helmond, Kim Greist, Charles McKeown, Tom Stoppard, and more. The participants end up trying to explain what the film is about without having seen the final results, and with no knowledge of the post-production hell that was about to be unleashed. Even Gilliam appears relatively calm and unperturbed—ordinary Gilliam cynicism, not wounded animal cynicism. There’s also some priceless behind-the-scenes footage, including work on the sea of eyeballs dream sequence that ended up being eliminated from the final cut.

The Production Notebook is a compilation of supporting material assembled by Brazil expert David Morgan. We’re All in It Together: The Brazil Screenwriters features Gilliam, Charles McKeown, and Tom Stoppard discussing the development of the script—Stoppard confirms that he helped to provide a structure for the film, and he also details the back-and-forth over the “My God, it works!” line. Dreams Unfulfilled: Unfilmed Brazil Storyboards are a collection of eight of Gilliam’s storyboards for his original conception of the dream sequence progression. While they were originally included as a still-frame supplement, they’ve been animated for this version, accompanied by narration from Morgan. Brazil’s Score features Gilliam and Michael Kamen discussing the overall score for the film and the inclusion of Ary Barroso’s Aquarela do Brasil (although Strauss was really Kamen’s primary inspiration).

The rest of the Production Notebook material consists of visual essays by Morgan. Designing Brazil mixes clips from the film with stills that were also originally included in the LaserDisc’s still-frame supplements. It’s fascinating, because many of the more bizarre design elements in Brazil had real-world inspirations. Flights of Fantasy: Brazil’s Special Effects focuses on the primarily in-camera effects work in the film. It includes some invaluable behind-the-scenes footage. Fashion and Fascism: James Acheson on Brazil’s Costume Design includes both interviews with Acheson and examples of his costume artwork.

The Battle of Brazil: A Video History is an eight-part documentary based on Jack Matthew’s book. Matthews serves as host and narrator, with Gilliam, Arnon Milchan, Frank Price, Marvin Antonowsky, Bob Rehme, and Sid Sheinberg appearing via interview footage (a few of them are audio only). Matthews freely admits that his love of Brazil means that he’s not going to offer an unbiased perspective, but the fact that even Sheinberg is included, in his own voice, means that the documentary still acknowledges different points-of-view. For those who don’t have his book, it offers an invaluable overview (although you really should buy the book, dammit).

Last (and most certainly least) is Brazil: The “Love Conquers All” Version, the legendary Sid Sheinberg recut in all of its 94-minute glory. It was only ever shown on television, so it’s included here in upscaled standard definition at a 1.33:1 aspect ratio, with English Dolby 2.0 Dolby Digital audio, as well as an optional commentary track by David Morgan. It’s included mostly for archival purposes, since it’s so bad that it’s difficult to watch—I’ve owned every single Criterion release of Brazil all the way back to LaserDisc, and I’ve never been able to get through it from beginning to end, even to listen to Morgan’s commentary. (Oh, and for everyone who complains about Blu-ray and UHD prices these days, it’s worth pointing out that we all had to shell out $150 for that set in 1990 dollars, up from Criterion’s standard $125, in no small part due to the last-minute inclusion of the Sheinberg cut.)

What’s still missing, unfortunately, is the U.S. theatrical cut, and while I’ve made my preferences clear in that regard, Gilliam’s preferences are a pipe of a different color. It is what it is. Not all of the still-frame supplements from the LaserDisc have been carried forward, including the script comparisons that were ported over to DVD but ended up being dropped for Blu-ray. (It’s a shame that Criterion has completely turned its back on a supplement format that they helped to pioneer.) Otherwise, this is as complete of a Brazil as we’re ever going to see, and the new 4K master is a major upgrade over the previous one. It’s nearly the equal of the sensational Grover Crisp-supervised 4K master that Sony provided to Criterion for their release of The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, and that’s really saying something. If you already own Criterion’s old Blu-ray release of Brazil, this one is well worth the upgrade, and if you don’t, what’s wrong with you? Don’t wait for Father Christmas, and pick this one up forthwith.

We’re all in it together, kid.

-Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter, Facebook, BlueSky, and Letterboxd).