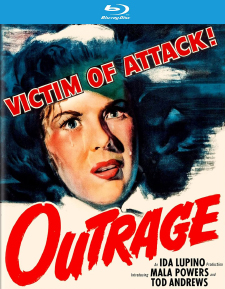

Outrage (1950) (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Ida LupinoRelease Date(s)

1950 (August 8, 2023)Studio(s)

The Filmmakers/RKO Radio Pictures (Kino Lorber Studio Classics)- Film/Program Grade: A-

- Video Grade: B+

- Audio Grade: B+

- Extras Grade: B+

Review

Actress Ida Lupino’s second credited feature as director (and, here, as co-writer), Outrage (1950), is an impressive drama (with noir elements) about a rape and its aftermath. Though hardly the first Hollywood to depict a sexual assault, with many such scenes in silent films and during the pre-Code era, as well as in Johnny Belinda (1948), a huge box-office and critical success, Outrage grapples with the same topic on a much more honest and personal level, and less melodramatically.

Ann Walton (Mala Powers) is a teenage bookkeeper at a small-town mill who becomes engaged to longtime boyfriend Jim Owens (Robert Clarke). Soon after, leaving work late one night, Ann is stalked by the man operating a food truck outside the mill’s front offices. She’s raped and in a state of shock returns home to her parents (Raymond Bond and Lilian Hamilton), who call for a doctor and summon the police. Ann has only vague memories of her attacker, limited to a large scar on the man’s neck and the leather jacket he was wearing. She tries returning to work, but is overwhelmed by the real and/or imagined stares and gossip about her.

Believing the entire town is now defining her by the attack and unable to cope, she up and leaves, running away and eventually landing in a small town outside of Los Angeles. Exhausted and with a sprained ankle, she encounters Bruce Ferguson (Tod Andrews), a Protestant reverend who suspects Ann is a runaway but is unaware of her rape. Patient and non-judgmental, he helps get her a job at a local orange farm owned by his friends Tom and Madge Harrison (Kenneth Patterson and Angela Clarke). Ann gradually comes to trust the sensitive Bruce, though the progress he steadily makes with her has a profound setback when, at a local dance, she’s accosted by farm worker Frank (Jerry Paris) and, experiencing flashbacks and imagining that he’s the man that raped her, hits him over the head with wrench, critically injuring him.

After decades and hundreds of episodes of empathetic TV dramas like Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, it would be easy but unfair to dismiss Outrage as sincere if dated. At the time it was made, sexual harassment and assault were, like cancer, topics not discussed in polite company and very rarely in films, commonplace problems largely swept under the rug, as if they would go away if never discussed. Psychological counseling and support groups for rape victims were virtually non-existent, and the culture of the time put far too much responsibility on women rather than men. Even within the film, the character of Frank is treated as a basically decent guy who merely gets “fresh” with Ann, he unaware of Ann’s fragile state, rather than as he would most certainly be depicted today, as a sexual predator refusing to take “no” for an answer.

Thus, Ann’s obvious feelings of being completely isolated, her very identity transformed in an instant, with even those closest to her, no matter how well-meaning, utterly incapable of comprehending the torrent of extreme emotions she’s experiencing, is all unnervingly honest.

There’s probably no way to determine this, but it would be interesting to know how the release of Outrage impacted real-life rape victims who saw the film then. Its advertising suggested a routine crime noir. Did rape survivors in 1950 who stumbled upon the film experience flashbacks themselves? Did Ann’s story resonate on a deep, personal level? Could Rev. Ferguson’s empathy by proxy help them in their recovery? I wonder.

Likely by design combined with budgetary restrictions, Lupino cast Outrage with relative unknowns, a contrast to Johnny Belinda that adds enormous verisimilitude. Mala Powers, a student and close friend of Michael Chekhov (she was the executrix of his estate), was just 18 years old in her first starring film (she had minor roles in two others before this), yet her performance is quite remarkable, especially when one notes the contrasting states of her character at the beginning, middle, and end of the story. Tod Andrews was primarily a stage actor—he replaced Henry Fonda for the touring company of Mister Roberts—but in films he was mostly limited to Poverty Row potboilers like Return of the Ape Man and, later, in cheapies like From Hell It Came. Who knew he was so capable of carrying such a delicate leading role? Others in the cast, such as Hal March, Jerry Hausner, and Vic Perrin, seem to have been drawn from the ranks of radio more than as recognizable character players in movies.

(Spoilers) Some critics find Rev. Ferguson’s saintly handling of Ann hard to swallow, or that the film’s suggestion of a budding romance is abruptly kiboshed when he sends her packing on a bus ride back home. Clearly the narrative needed someone with the patience and sensitivity to encourage Ann to find her own answers and start rebuilding her life, and to simply listen without judging or gaping at her like a carnival attraction. Quite reasonably, Ann experiences what psychologists call transference, a shifting of her love for Jim to Bruce that Bruce is wise enough to recognize. The emotional barrier he creates by sending Ann home is precisely what psychologists do when a patient’s therapy is at an end. Was this instinctive plotting on the part of the filmmakers or did they consult a trained psychiatrist? And in making Ferguson a reverend and thus “safe” around Ann, conversely there’s a welcome lack of “God talk.” Ferguson never tries to define (or excuse) Ann’s assault with passages from The Bible.

Both Lupino’s direction and the screenplay make intelligent choices throughout. It eschews a big trial scene, and almost literally all the audience sees of the criminal investigation is what Ann herself is witness to. Indeed, the identity and eventual capture of Ann’s rapist becomes incidental. This is Ann’s story, not his, nor is it shared with some tireless police detective. It’s a woman’s story in every sense.

Made independently by The Filmmakers, a company Lupino founded with her then-husband Collier Young, for release through RKO, the film changed hands through the years, eventually landing with Paramount. Probably for this reason, no original camera negative was available, Paramount apparently sourced a 35 mm fine grain for this video master. It may not be as pristine as an OCN would be, but it’s perfectly presentable, looking just fine on my projection set-up and its 150-inch screen. The DTS-HD Master Audio (2.0 mono) is likewise fine, and supported by optional English subtitles. Region “A” encoded.

There’s just one extra feature but an unusually good one: an informative, insightful audio commentary track by historian Imogen Sara Smith.

Outrage may at first appear dated, but really it offers a pretty accurate view of how taboo the subject of rape was in 1950, and how unimaginatively more difficult it must have been for victims then in a society that, by and large, hadn’t a clue how to treat woman in its aftermath. Highly Recommended.

- Stuart Galbraith IV