“Just think about that incredible introduction as Ursula Andress emerges from the water for the first time. It’s one of the great moments of ‘60s cinema.” — 007 and film/TV music historian Jon Burlingame

The Digital Bits is pleased to present this retrospective commemorating the 55th anniversary of the release of Dr. No, the first cinematic James Bond adventure.

As with our previous 007 articles (see The Living Daylights, The Spy Who Loved Me, You Only Live Twice, Diamonds Are Forever, Casino Royale, For Your Eyes Only, Thunderball, GoldenEye, A View to a Kill, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Goldfinger, and 007… Fifty Years Strong), The Bits and History, Legacy & Showmanship continue the series with this retrospective featuring a Q&A with an esteemed group of James Bond scholars, documentarians and historians who discuss the virtues, shortcomings and legacy of Dr. No. [Read on here...]

The participants (in alphabetical order)…

Jon Burlingame is the author of The Music of James Bond (Oxford University Press, 2012). He also authored Sound and Vision: 60 Years of Motion Picture Soundtracks (Watson-Guptill, 2000) and TV’s Biggest Hits: The Story of Television Themes from Dragnet to Friends (Schirmer, 1996). He writes regularly for the entertainment industry trade Variety and has also been published in The Hollywood Reporter, Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, and The Washington Post. He started writing about spy music for the 1970s fanzine File Forty and has since produced seven CDs of original music from The Man from U.N.C.L.E. for the Film Score Monthly label. His website is www.jonburlingame.com.

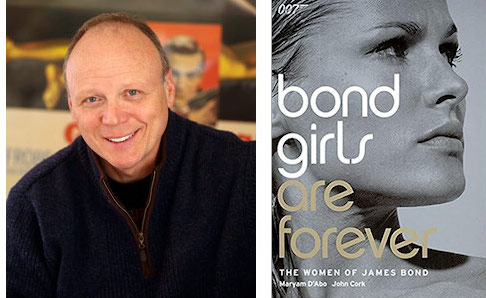

John Cork is the author (with Collin Stutz) of James Bond Encyclopedia (DK, 2007) and (with Bruce Scivally) of James Bond: The Legacy (Abrams, 2002) and (with Maryam d’Abo) Bond Girls Are Forever: The Women of James Bond (Abrams, 2003). He is the president of Cloverland, a multi-media production company, producing documentaries and value added material for movies on DVD and Blu-ray, including material for many of the James Bond and Pink Panther titles as well as Chariots of Fire and The Hustler. Cork also wrote the screenplay to The Long Walk Home (1990), starring Whoopi Goldberg and Sissy Spacek. He wrote and directed the feature documentary You Belong to Me: Sex, Race and Murder on the Suwannee River for producers Jude Hagin and Hillary Saltzman (daughter of original Bond producer, Harry Saltzman). He has recently contributed articles on the literary history of James Bond for ianfleming.com and The Book Collector.

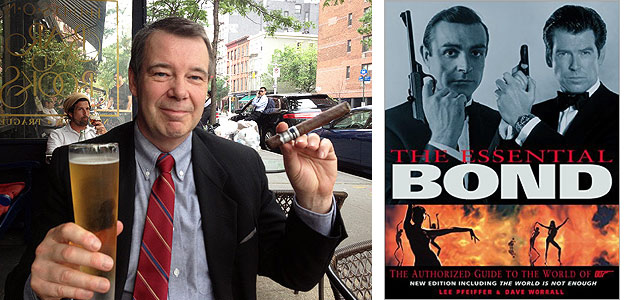

Lee Pfeiffer is the author (with Dave Worrall) of The Essential Bond: The Authorized Guide to the World of 007 (Boxtree, 1998/Harper Collins, 1999) and (with Philip Lisa) of The Incredible World of 007: An Authorized Celebration of James Bond (Citadel, 1992). He also wrote The Films of Sean Connery (Citadel, 2001) and (with Michael Lewis) The Films of Harrison Ford (Citadel, 2002). Lee was a producer on the Goldfinger and Thunderball Special Edition LaserDisc sets and is the founder (with Dave Worrall) and Editor-in-Chief of Cinema Retro magazine, which celebrates films of the 1960s and 1970s and is “the Essential Guide to Cult and Classic Movies.”

Steven Jay Rubin is the author of The James Bond Films: A Behind-the-Scenes History (Random House, 1981) and The Complete James Bond Movie Encyclopedia (McGraw-Hill, 2002). His other books include The Twilight Zone Encyclopedia (Chicago Review, 2017) and Combat Films: American Realism, 1945-2010 (McFarland, 2011), and he has written for Cinefantastique and Cinema Retro.

Graham Rye is the author of The James Bond Girls (Boxtree, 1989) and the editor, designer and publisher of 007 Magazine.

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

And now that the participants have been introduced, might I suggest preparing a martini (shaken, not stirred, of course) and cueing up the soundtrack album to Dr. No, and then enjoy the conversation with these James Bond authorities.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): In what way is Dr. No worthy of celebration on its 55th anniversary?

Jon Burlingame: In so many ways we can’t possibly count them! How much poorer would our lives have been without James Bond movies for the past 50 years?! It’s really unthinkable when you consider the enormous cultural impact over the years of Ian Fleming, James Bond, Cubby Broccoli & Harry Saltzman, even composer John Barry (whose initial fame stemmed from his association with the 007 franchise).

It’s where it all started. And while the film hasn’t aged as well as some others in that first decade, it did have that amazing sense of style, that impressive story and indelible characters, the larger-than-life spy plot that we had not really encountered before in films. When you think of what director Terence Young and star Sean Connery managed on a fairly limited budget, it’s really remarkable. And of course it launched an entire series — today we’d call it a “franchise” — of movies that influenced a generation in how to think about espionage and East-West relations, and in some ways predicted the dark and dangerous side of global corporate entities that didn’t have people’s best interests at heart, only their own (“counter-intelligence, terrorism, revenge and extortion,” one might say).

John Cork: Dr. No gave us the cinematic James Bond, the James Bond Theme, the gunbarrel opening, the first of the Maurice Binder title sequences, and Ursula Andress walking from the sea in her white bikini. The film also gave audiences Sean Connery as a major star. Something shifted with Dr. No. When Bond basically coerces Miss Taro into having sex with him (twice) and then shoots Professor Dent in the back, audiences saw a different kind of ruthless hero. Bond was not portrayed as a damaged man, like John Wayne in The Searchers or Red River or T.E. Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia, but a figure to be admired, whose morals are never brought into question. It was startling and felt completely new.

Dr. No is a fantastic film. It may seem a bit less outlandish than later Bonds to some, but the movie has everything: exotic locales, elegance, sex, action, adventure, and one of the great film villains. Yes, a few of the performances are clunky, and the back projection feels like…back projection, but, news alert, in fifty-five years the CGI in the Marvel movies isn’t going to hold up very well, either. There is a thick dose of racism that informs the character of Quarrel, which thankfully gets horrified laughter and even groans from modern audiences. But mostly, there is the character of Bond who embodies so many masculine ideas. He is dangerous, intelligent, elegant, confident, and sexually attractive to women. This is a difficult combination to beat, but equally a difficult combination to pull off on film without lapsing into pompousness or self-parody. What Terence Young and Sean Connery delivered was a game-changer.

Lee Pfeiffer: Dr. No’s influence on the action cinema genre is incalculable. Not only did the film introduce an iconic screen hero to international audiences, the movie changed the entire look and feel of action/adventure films. There was plenty of credit to go around beginning with a script that allowed the hero to be witty and not take the developments too seriously. Terence Young was the perfect director. He played up the surrealistic aspects of the film without ever devolving into satire or slapstick. There was also the influence of Peter Hunt, whose fast-style editing of quick cuts proved to be widely influential. Then there were the musical contributions of Monty Norman, who composed the James Bond Theme, and John Barry who orchestrated it so memorably. Most obviously was the casting of Sean Connery. Had an actor not so well-suited to the role of Bond been cast, the series might have been short-lived. The film did well at the box office but was not a blockbuster. It did, however, pave the way for the future Bond movies which were blockbusters. I believe that Dr. No probably made more money on reissues than it did during its initial run. Because Bond movies came out in those days in relatively rapid succession, the momentum established with Dr. No was able to build exponentially and very quickly. With the release of Goldfinger a scant two years later, Bond was already an international phenomenon.

Lee Pfeiffer: Dr. No’s influence on the action cinema genre is incalculable. Not only did the film introduce an iconic screen hero to international audiences, the movie changed the entire look and feel of action/adventure films. There was plenty of credit to go around beginning with a script that allowed the hero to be witty and not take the developments too seriously. Terence Young was the perfect director. He played up the surrealistic aspects of the film without ever devolving into satire or slapstick. There was also the influence of Peter Hunt, whose fast-style editing of quick cuts proved to be widely influential. Then there were the musical contributions of Monty Norman, who composed the James Bond Theme, and John Barry who orchestrated it so memorably. Most obviously was the casting of Sean Connery. Had an actor not so well-suited to the role of Bond been cast, the series might have been short-lived. The film did well at the box office but was not a blockbuster. It did, however, pave the way for the future Bond movies which were blockbusters. I believe that Dr. No probably made more money on reissues than it did during its initial run. Because Bond movies came out in those days in relatively rapid succession, the momentum established with Dr. No was able to build exponentially and very quickly. With the release of Goldfinger a scant two years later, Bond was already an international phenomenon.

Steven Jay Rubin: Dr. No is worthy because it was the first movie in the series and established the ground rules for much of the films that followed. Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli also put together a killer team on both sides of the camera. They gave Sean Connery his first true starring role in a major feature, paving the way for films that achieved enormous success in the international box office. They paired writer Richard Maibaum with director Terence Young, a great combination. They brought in production designer Ken Adam, editor Peter Hunt, stuntman Bob Simmons, cameraman Ted Moore, and many other artists who brought their A game to a little film budgeted just north of $1 million. And they delivered a wonderful adventure film that is truly underrated in the 007 canon.

Graham Rye: It’s not only the James Bond film that started the record-breaking James Bond film series but also the spy craze in international cinema. It was a unique groundbreaking picture for its time and set so much more in motion it should be celebrated every 10 years forever!

Coate: Can you describe what it was like seeing Dr. No for the first time?

Burlingame: Sorry to say that I was only 9 when it was released in 1962 and I didn’t see it for several years. I had to catch up with the first five after I saw On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, and did so with various double-bill reissues, and was hooked forever after. And having already experienced the John Barry scores for the second through sixth films, I was a little startled by the musical hodgepodge that greeted me with the Dr. No score (the Barry-arranged Bond theme, the odd mix of Monty Norman songs and score, etc.). And then the differences between the score and the soundtrack album took years to unravel and understand.

Cork: I have no memory of the first time I saw Dr. No. It was the summer of 1965 on a double-bill with From Russia with Love. My mother says that we saw both films, but I was not quite four, and all I remember is one scene in From Russia with Love. I later saw the film on ABC when it premiered. I loved it, but by that time I was already obsessed with James Bond. The first time I saw it on the big screen as an adult was in the fall of 1980 at the Nuart in Los Angeles again on a double bill with From Russia with Love. I took the bus to the theater across town from the USC campus and then walked for miles to get back in the middle of the night. It was a great night at the movies, and one that really re-ignited my love of James Bond films.

Pfeiffer: The first Bond movie I saw was From Russia with Love on its U.S. release in 1964. I had actually wanted to see the second feature: Vincent Price in Twice Told Tales at the Loew’s Jersey City movie palace. I didn’t want to stay for the Bond film because, based on the title — and being an eight-year-old boy — I thought it would be a sappy love story about people in the Soviet Union. My father convinced me to stay and I’m glad he did because the Bond film blew me away. I had never seen an action movie like it. Later that evening, my older brother Ray informed me that there had been a previous Bond film, Dr. No, that he had seen. I became obsessed with seeing it, but of course in those days there was no home video. In 1965, they re-issued Dr. No with From Russia with Love as the first Bond double feature. It did phenomenal business and allowed those of us who hadn’t seen Dr. No to finally catch up with it. I loved the movie but remember being a bit puzzled. By this point I had seen Desmond Llewelyn twice in the role of “Q” and I couldn’t figure out why they had another actor, Peter Burton, play him in Dr. No. I was also a bit disappointed that there wasn’t a pre-credits sequence and no deadly gadgets. But I was greatly impressed by the film and especially Joseph Wiseman as Dr. No.

Rubin: I did not see Dr. No first run. The first two Bond films were released to Los Angeles theaters in 1963 [and 1964, respectively] to little fanfare. Like most of us, I caught the film when it was re-released on a celebrated double feature with From Russia with Love after the release of Goldfinger. I loved Dr. No. Connery was terrific, the women were gorgeous, Joseph Wiseman was a cool villain, and the film was well directed by Terence Young. With From Russia with Love, it was the probably the best four hours I’ve ever spent in a movie theater.

Rye: Its impact on me is clear to anyone who has followed the publication of 007 Magazine for the last three decades. When, as an 11-year-old I was taken to see Dr. No by my father at the Odeon Southall I could not in my wildest dreams at that age have imagined what I was going to see up there on that big screen in the dark with the wonderful aroma of every kind of tobacco smoke and hotdogs filling the auditorium. But as soon as it began I felt apprehensive; the unnerving electronic sounds that opened the picture, the white dot that paced across the screen, soon opening out into a view looking down a gun barrel, not through a camera iris as many people mistakenly thought (my Dad served in the Royal Navy during WWII and had firearms experience, so he was able to immediately explain to me in the cinema what it was), and a man in a hat (they wore them in those days) appears walking along as the gun barrel follows him until he quickly turns and surprisingly fires directly at me as a film of blood runs down the screen and a blast of brass stabs out the opening theme music before the blood has had a chance to reach the bottom of the screen, and the gun barrel wavers and moves down to change into a series of colored dots here, there and everywhere.

Rye: Its impact on me is clear to anyone who has followed the publication of 007 Magazine for the last three decades. When, as an 11-year-old I was taken to see Dr. No by my father at the Odeon Southall I could not in my wildest dreams at that age have imagined what I was going to see up there on that big screen in the dark with the wonderful aroma of every kind of tobacco smoke and hotdogs filling the auditorium. But as soon as it began I felt apprehensive; the unnerving electronic sounds that opened the picture, the white dot that paced across the screen, soon opening out into a view looking down a gun barrel, not through a camera iris as many people mistakenly thought (my Dad served in the Royal Navy during WWII and had firearms experience, so he was able to immediately explain to me in the cinema what it was), and a man in a hat (they wore them in those days) appears walking along as the gun barrel follows him until he quickly turns and surprisingly fires directly at me as a film of blood runs down the screen and a blast of brass stabs out the opening theme music before the blood has had a chance to reach the bottom of the screen, and the gun barrel wavers and moves down to change into a series of colored dots here, there and everywhere.

My eyes are assaulted by the shimmering colors until the first name appears on the screen “Ian Fleming’s” (who?) and the title Dr. No jumps all over the place making me feel as though I’m being subjected to the eye test from hell, then that twanging guitar of Vic Flick’s kicks in as a strip of colored squares flash the three numbers down the screen that are going to haunt me to the grave (but I don’t know it yet!) and eventually partner on screen with the words starring SEAN CONNERY,” that will have an even more spectral effect on him, but with the great side-effect of iconic fame and fabulous fortune. Colored dots, dots dots dots and more dots — I’ve often wondered what a color-blind person would have seen — until other names appear, none of whom mean anything to an 11-year-old schoolboy, but will later; some of whom I’ll interview and others who will even become friends. Wow! — bongos and dancing female and male red silhouettes overlap each other and replace the tub thumping brass as the Technicolored screen continues to dazzle and hypnotize me. Main title designed by MAURICE BINDER — remember that name Graham! Silhouettes of three blind men, blind beggars, three blind mice in the road, take over as they shuffle along to a calypso beat all the while, Produced by HARRY SALTZMAN & ALBERT R. BROCCOLI, Directed by TERENCE YOUNG — and dissolve into live action film of the three black men walking along a street, a street I later learn is in Kingston, Jamaica — but still with that light-hearted calypso tune with dark lyrics to accompany them on their way until they arrive at a sign that reads: “Queens Club PRIVATE MEMBERS ONLY” — and the lead blind beggar touches it as though he can read it by touch, even see it. Cut to four smart suited white men playing cards on a veranda, one of whom, Strangways, seemingly a nice chap, leaves the game to speak with his UK office on the telephone, while another man at the table orders more drinks, treating the black waiter he’s rung for in an arrogant, almost rude manner — not a nice chap. His look as Strangways walks away from the card game should tell me something. I don’t know how or why, but the arrogant card player knows exactly what is going to happen next. As Strangways passes the three beggars he places a coin in the first man’s begging cup, confirming for me he’s a decent chap. As he opens the door of his green Ford Anglia (my Grandmother would never have anything green colored in the house, she thought it was unlucky; and in this instance she was right!) three heavy coughs almost bark as one as Strangways’ body is hurled forward as though it has been kicked. The “beggars” aren’t blind and have shot the decent chap to death. In an instant Strangways’ body is dumped unceremoniously into a hearse which has sped into the drive, and in which the trinity of killers are chauffeured to their next hit — Strangways’ secretary Mary. Her killing is carried out just as quickly and abruptly, and mercilessly, and is even more shocking because it’s a woman, and it’s a bloody killing. Phew! All this in a breakneck opening few minutes, and I haven’t even met James Bond yet, or “M,” Moneypenny, Sylvia Trench, Quarrel, Felix Leiter, Honey Ryder — and of course, Dr. No. Over the years and after many viewings this film still remains, for me, the exciting and saucy introduction into a world that has brought me, and millions of people around the world, a great deal of pleasure and entertainment. With their instinctive abilities at being able to assemble the best possible talent around during that golden period of the 1960s, producers Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli, with a budget of barely a million dollars, managed to pull a gold-plated rabbit from a hat with Dr. No. No one at that time could possibly have dreamt the level of success this film would enjoy or that by 2002 its worldwide box office gross would have exceeded $59 million.