THE Q&A

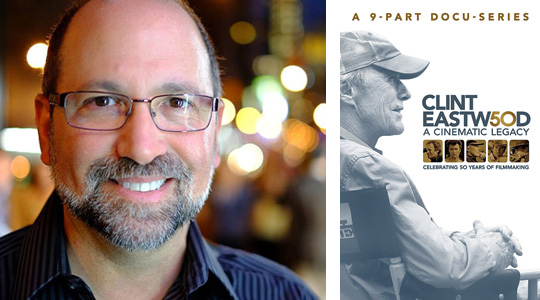

Gary Leva is the director and producer of the Clint Eastwood: A Cinematic Legacy documentary series (2021). He has directed and produced numerous other documentaries including Fog City Mavericks: The Filmmakers of San Francisco (2007) and value-added material for home media releases including Dirty Harry, Apollo 13, Sully, Singin’ in the Rain, THX 1138, and many others. Gary was previously interviewed for this column’s retrospectives on THX 1138 and Raiders of the Lost Ark.

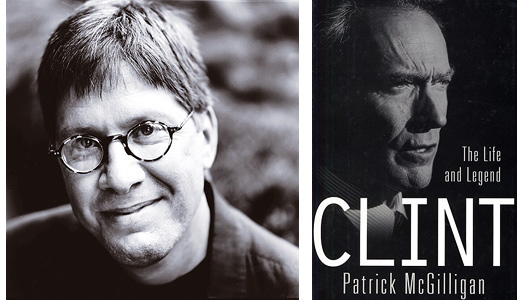

Patrick McGilligan is the author of Clint: The Life and Legend (St. Martins, 2002). He has authored over ten books, including Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (Harper Collins, 1994), Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast (St. Martins, 1997), Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane (Harper Collins, 2015), and Funny Man: Mel Brooks (Harper Collins, 2019). Patrick was previously interviewed for this column’s retrospective on Citizen Kane.

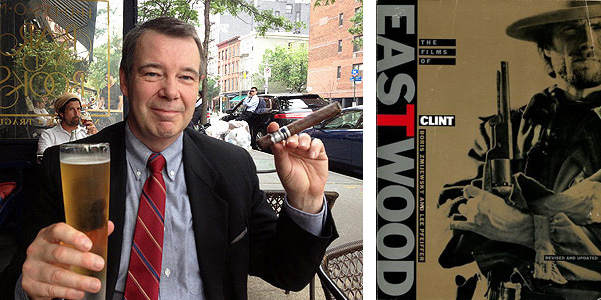

Lee Pfeiffer is the editor-in-chief of Cinema Retro magazine (“The Essential Guide to Movies of the ‘60s & ‘70s”). He has written numerous books including The Films of Clint Eastwood (with Boris Zmijewsky; Citadel, 1993), The Essential Bond: The Authorized Guide to the World of 007 (with Dave Worrall; Boxtree, 1998/Harper Collins, 1999), and The Incredible World of 007: An Authorized Celebration of James Bond (with Philip Lisa; Citadel, 1992). Lee has been interviewed numerous times for this column’s retrospectives, including for Shaft, Smokey and the Bandit, and numerous James Bond movies.

The interviews were conducted separately and edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): How do you think Dirty Harry ought to be remembered on its 50th anniversary?

Gary Leva: What stands out to me about Dirty Harry is its sense of humor and irreverence. So many cop movies before it were glum, joyless exercises. Though there’s a lot of violence and even moments of absolute terror in it—particularly the sequence with the kids on the bus—Siegel manages to bring a sense of fun to it, almost a feeling of adventure, despite the dark subject matter.

Patrick McGilligan: Dirty Harry is the film that cemented Clint’s iconic tough-guy persona and enabled Life magazine to put him on its cover with this headline, "The World’s Favorite Movie Star is—No Kidding—Clint Eastwood." The Spaghetti Westerns already had made Clint a star in Europe, but Dirty Harry made him a big star in America, a position he has held—with regular Top Ten box-office hits—for over fifty years now. Its story and characters attuned to the times, its controversial politique, Clint’s central performance (and one of the most villainous villains he’d ever face on the screen), gave the film an unprecedented (for Clint) popularity with audiences, and was not only a must-see at the time, it remains a must-see today as one of his best films, one of the best American films of the early 1970s, and an influential film in terms of others in the culture (others with Clint and imitators and emulators) that followed. It also remains controversial for its repudiation of legalities and its endorsement of vigilante justice.

Lee Pfeiffer: The film was one of a number of crime dramas that perfectly captured the mood of the nation at that particular point in time. America was coming out of the contentious period of the mid-to-late 1960s when the nation seemed to be falling apart due to a variety of factors. The Vietnam War was still raging and was more controversial than ever. Race riots had scarred major cities over the last few years. The country was still trying to cope with the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy. The Democratic party was in meltdown and their Chicago convention devolved into violent chaos in the streets, leading the political resurrection of Richard Nixon. It was a pretty awful time despite the fact that many people tend to romanticize the era due to the great aspects of popular culture that had emerged. The nation’s big cities were awash with crime and the general feeling was that the judicial system had failed and the police were compromised by ineffective policies and laws. Dirty Harry played to those sentiments. I would also include Taxi Driver and Death Wish as equally relevant examples. These films dealt with vigilantes, albeit in a different manner. Taxi Driver presented a would-be villain who, through a quirk of fate, happened to kill the right people and emerge as a local hero. But Dirty Harry and Death Wish celebrated protagonists who took the law into their own hands to go after overt villains. One of the ad campaigns designed by the late, great Bill Gold, who would go on to create the posters for most subsequent Eastwood films, captured the scenario perfectly with this tag line: “Dirty Harry and the homicidal maniac. Harry’s the one with the badge.” The movie resonated with audiences in a way that I doubt even the Warner Bros. brass would have imagined.

The Digital Bits: What was your first impression of the film?

Pfeiffer: I don’t know why men always seem to remember exactly where they saw certain films, but it seems to be the case with my generation. I saw it in my hometown of Jersey City, New Jersey, just a stone’s throw across the Hudson River from midtown Manhattan. The Loew’s was an opulent, former movie palace and a great place to see movies. I was enthused about seeing Dirty Harry because I had been an Eastwood buff since seeing Fistful of Dollars when it was released in America in 1967. I had never seen a hero like Eastwood…he was the ultimate antihero, a rougher version of my idol John Wayne. The TV spots and trailers for Dirty Harry had built up expectations and the film delivered. I would see it multiple times during its first run.

Leva: I was a kid when the film came out in 1971, so I couldn’t get into an R-rated movie. I must have seen it years later, probably on television. I remember being struck by the film’s energy, its forward movement, driven by a character bent on finding justice for someone he’d never even met.

McGilligan: I saw the film while in college at the University of Wisconsin in Madison at the time of its release, and I was on the fringe of a left-wing group of mostly East Coast sophisticates that worked to put out a film journal called The Velvet Light Trap. One of these sophisticates, a writer named Anthony Chase who went on to become a law professor and legal writer, dissected the film in a famous essay attacking its fascistic qualities—namely, the scorn for lawyers, judges, government officials and law professors; Harry taking the law into his own hands and "executing" Scorpio, etc. I agreed and still agree with Tony Chase, who later wrote a book about this and other films called Movies on Trial: The Legal System on the Silver Screen. (Pauline Kael dismantled Dirty Harry on much the same grounds, while also attacking Clint’s narcissism.) But part of Dirty Harry’s enduring strength is that, despite all this and also in part because of this, the film is exciting to watch and superbly well-made.

The Digital Bits: In what way is Dirty Harry a significant motion picture?

McGilligan: The film is significant historically and politically because of all the societal issues it contextualizes, some of which are still current—Dirty Harry as a symbol of a certain law-and-order mindset, for example—but also it can be seen, more narrowly in terms of American film history, as an important work for launching Clint’s career and persona (along with the Leone films) and for normalizing the kind of violence, nudity, and themes in the American cinema that are taken for granted nowadays but were still fresh in the early 1970s. Also, it gave rise to a whole sub-genre of filmmaking with police or victims avenging crimes regardless of the law—Death Wish, etc.

Pfeiffer: For the reasons previously stated, the film went beyond being a popular success. It touched a nerve in society and generated a lot of controversy, with some critics calling it an approval of fascism. It would be an exaggeration to say that movie started the rogue cop genre. One can go back three years earlier to Steve McQueen in Bullitt and then William Friedkin’s The French Connection, released a couple of months before Dirty Harry, as having that designation. But Dirty Harry carried the genre to new highs, or lows, depending upon your point-of-view. It played to populist notions, as films of this type must do. There are no nuances when it comes to the bad guys. That’s important if you are going to get audience members cheer a protagonist who intentionally violates suspect’s constitutional rights. The villains have to be pure scumbags with no redeemable qualities. The scenario has to be laid out in relatively simplistic terms: the bad guy is irredeemable, the victims are pure and innocent and the hero only breaks the rules because “the system” has tied his hands. The film presents one of cinema’s most memorable psychopathic villains, Scorpio. He’s chillingly played by Andrew Robinson in a performance that deserved an Oscar nomination for Supporting Actor.

Leva: I think the film’s long-lasting significance is its influence on the cop film genre. The character of Dirty Harry had attitude, and the hundreds of cop films released in the 50 years since reflect this element to one extent or another. Certainly, without Dirty Harry, there is no Lethal Weapon. And that’s true of so many other films as well.

Pfeiffer: Dirty Harry, and most especially Death Wish, inspired a slew of similarly-themed copycat movies and TV productions that emulated the oppressed good guy having to seek justice on his own terms. It’s doubtful the film could be made today. Rogue cops are no longer in style but, viewed through a retroactive lens, the movie has a timeless quality. I should mention that much of the credit must go to the screenwriters, Harry Julian Fink, Rita M. Fink and Dean Riesner. They knew the mindset of the audience during this era of populist cinema and their script hits all the right notes.

The Digital Bits: In what way was Don Siegel an ideal choice to direct?

Leva: Don Siegel’s simplicity and efficiency in storytelling, coupled with his signature sense of forward momentum, meshed nicely with the script and Eastwood’s performance. There’s a no-nonsense quality to Siegel’s work that certainly characterizes Clint’s performance as well. There aren’t a lot of artsy shots or fancy angles. It may be the perfect synthesis of Siegel’s directing gifts and Eastwood’s talents as a screen actor.

McGilligan: The main reason why Don Siegel was the perfect choice to direct the film was his previous track record with Clint—several films with an interesting range but among them a cop film (Coogan’s Bluff) that was a Harry-forerunner. Siegel was long considered an action director who could bring a thoughtful or thematic dimension to his work, sometimes a B director but with a stylish A atmosphere and performances. He had a close relationship with Clint dating back years, Clint trusted him, and Clint took his own quick and lean directing approach partly from Siegel, who has a cameo in Play Misty for Me, Clint’s first directorial effort, which he made around the same time as Dirty Harry (and in the same northern California vicinity). Siegel’s team, which included the finishing writer on Dirty Harry, followed him from film to film, and Clint borrowed some of these same people when he moved into directing. Arguably, Siegel’s Dirty Harry film was better than any of Clint’s many follow-ups, but inarguably Siegel set the template. Also arguably, Clint was a better actor under another director besides himself, and he was never better than in Dirty Harry.

Pfeiffer: Siegel was one of those directors who was respected as being talented and reliable but never received effusive praise. He had generally been assigned to low-budget films and his talents, like those of so many of his peers, were regarded as workmanlike. However, he would see his reputation rise as a new generation of movie fans appreciated his direction of the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers, which by the 1970s, would be regarded as the classic it is. Eastwood and Siegel first collaborated unexpectedly. Alex Segal had been hired to direct Eastwood’s 1968 crime thriller Coogan’s Bluff but he became unavailable for some reason. The studio told Eastwood that Don Siegel would take over, leaving Eastwood to gripe that Universal didn’t seem to have anyone without that surname available to do the film. But he and Siegel hit it off immediately. Eastwood was already eager to move into directing and he had learned a great deal from Sergio Leone. Now, Siegel would become even more influential. He worked on a fast schedule, shooting rapidly and trying to get each scene on the first take. He expected the same of his cast and crew. That appealed to Eastwood. He and Siegel would collaborate again in short order on Two Mules for Sister Sara and an underrated gem, The Beguiled before teaming for Dirty Harry. Prior to Harry, Eastwood made his directorial debut with the thriller Play Misty for Me which had been released earlier in the year. By this point, Siegel had been like a father figure and mentor to him. To bolster his confidence, Eastwood wanted to have Siegel on the set, so he hired him for a supporting role. Siegel proved to be a very good actor, too. Unfortunately, after Dirty Harry, the two men would only collaborate one more time—for the 1979 crime film Escape from Alcatraz, probably because Eastwood quickly became comfortable directing most of his own movies. Don Siegel died in 1991 but he lived long enough to see his work and reputation re-evaluated in a very positive light.

The Digital Bits: Which are the film’s standout scenes?

Pfeiffer: There are many. Probably the most famous is where Harry first places his .44 Magnum in the face of a wounded bank robber and asks him the question “Do I feel lucky?” before clicking the weapon in a bizarre game of Russian Roulette. Then there’s Harry’s leap atop the hijacked school bus. However, my favorite scene follows the scenario in which Scorpio wants to frame Harry for police brutality so he hires another bad guy to beat his face to a bloody pulp. When Harry is confronted with the accusation, he says anyone can tell he wasn’t responsible for Scorpio’s appearance “because he looks too damned good.”

Leva: I love the first action sequence where Harry stops the robbery and says “You’ve got to ask yourself one question: Do I feel lucky? Well, do ya, punk?” The iconography of it is right out of a Western. I love the shot of Albert Popwell’s hand twitching next to his rifle with the shadow of the .44 Magnum falling on the sidewalk. It’s shot right out of a John Ford Western. The whole standoff between them, the tense shots of their faces, the close-up of the gun… it could be the streets of Tombstone… or whatever town it was in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly…. But the best thing in the scene—and the thing that’s unique—is what follows. Harry starts to walk away and Popwell says, “I gots to know.” Harry walks back, points the Magnum at him and pulls the trigger, scaring the life out of Popwell. The gun clicks, empty. Harry laughs and walks away. I’d never seen that before. That announced to audiences that this was going to be a different kind of cop movie….

McGilligan: The rooftop opening murder, which is eerie and disturbing, and is quickly followed by Clint/Dirty Harry investigating the scene, which shrewdly introduces him as the titular character. The Harry-is-interrupted-while-eating-a-hot-dog bank robbery in downtown San Francisco (ending with "Do ya feel lucky, punk?"). The football stadium showdown between Harry and Scorpio, which like many scenes takes place at night and is pure action cinema. The somewhat absurd climax of the film, which is nonetheless mesmerizing, beginning with Scorpio terrorizing kids inside a school bus and segueing to Clint/Harry leaping from above the highway onto the bus and then holding on to the careening bus as Scorpio, driving, tries to throw him off and crashes the bus. Any one of these scenes would be a standout in another film. All of them—and others—taken together lift Harry to greatness.

Leva: The other sequence I love is when Zodiac takes over the school bus. It’s such an over-the-top idea to begin with. And forcing the kids to sing Row, Row, Row Your Boat during this terrifying sequence echoes another film that came out in 1971, with Malcolm McDowell’s doing Singin’ in the Rain in A Clockwork Orange as he brutalizes a couple in their home…. And then the bus drives by a bridge and you see Harry, again echoing Western iconography, standing alone on the bridge—the lone hope for order in a world of chaos. Like Shane, or Ethan Edwards in The Searchers.

The Digital Bits: Any thoughts on Clint’s performance in the film?

McGilligan: Dirty Harry ranks among his five greatest performances certainly: My top five would include The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, maybe White Hunter, Black Heart with Clint as John Huston, which is a clever impersonation, and I’m not sure of the fifth. Clint typically didn’t put the same demands on himself as a performer that some other directors did, in my opinion.

Leva: I can’t imagine anyone else playing Harry as well as Clint does. I’m sure there were a few people on the list—I know Frank Sinatra was the original choice—but Clint’s talents and no-nonsense style are a perfect match for Harry.

Pfeiffer: I remember the controversial reviews and one critic had said Eastwood must have attended the Mount Rushmore Acting Academy. It’s true that prior to this, he had played largely stoic, one-dimensional characters, with the exception of The Beguiled, in which he played a rather villainous character for the first and only time and acquitted himself very well. But I could tell with Dirty Harry there were some indications he had much greater acting abilities. Like most actors, Eastwood would hone his skills over time and become a more interesting screen presence as he aged. He was nominated for Best Actor for his 1992 classic Unforgiven, which won him the Best Picture and Director Oscar. As few people had seen his fine performance in The Beguiled since it was a rare Eastwood boxoffice flop, most people would attribute his performance in Dirty Harry as being the first evidence that he was more than simply a fun action hero.

McGilligan: Clint’s best scene? The scene where he walks down flights of steps with his partner’s wife (they have just visited his partner recovering from his wounds in the hospital), in which Harry speaks movingly of his dead wife, is one of Clint’s best "quiet" scenes. Both of the "Do ya feel lucky, punk?" scenes are Clint at his best—mocking himself a little the first time, which is why audiences always chuckle a little—and the second time fierce, angry, and determined to kill. Again, Siegel and the script demand a range from him as an actor in this film that is not as challenging in the sequels, or all the many other Dirty Harry-type films Clint has made.

Pfeiffer: In the late 1970s, as I was getting ready to graduate college, I decided to write a book about Eastwood’s films. Much to my surprise, I found a publisher right away. When I submitted the manuscript, however, my editor said to me something like, “Look, we all like Clint Eastwood movies but you’re going overboard in regard to his talents.” I believed even then that Eastwood had the potential to grow as an actor and filmmaker into an artist of considerable esteem. There were a few bumps in the road, but overall, he fulfilled my expectations. But there’s no doubt that, by and large, the critical establishment was resistant to his work. It’s strange to see so many of today’s critics hail Eastwood’s work with Sergio Leone and Don Siegel as classics, when back in the day, reviewers largely dismissed these films as examples of mindless violence.

Leva: Clint would give more moving, powerful performances later, of course, particularly in Unforgiven, Million Dollar Baby, Gran Torino and The Mule, but I think his performances in the five Dirty Harry films hold up just fine.

Pfeiffer: Interestingly, Eastwood was not Warner Bros.’ first choice to play the role of Harry. Frank Sinatra has been signed for the film and the studio took out trade ads announcing it. However, Sinatra suffered a hand injury and had to withdraw. John Wayne was approached but he turned it down on the basis that the script would be deemed to be alienating for his core audience. He was probably right. The film would have had to have been watered down to accommodate Wayne’s concerns. Curiously, after Dirty Harry became a sensation, it inspired Wayne to get out of the saddle and make two detective movies of his own, McQ and Brannigan, both of which proved to be quite entertaining and popular.