CHAPTER 1: THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY

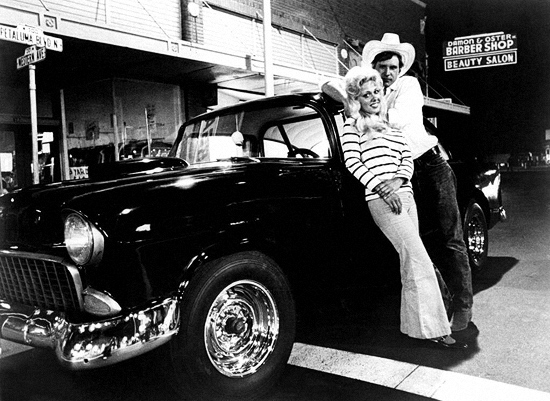

Ray Morton (author, Close Encounters of the Third Kind: The Making of Steven Spielberg’s Classic Film): First and foremost [it should be remembered on its 50th anniversary] as a terrific movie—funny, touching, and wildly entertaining. As a film that captured a specific time and place about as well as any movie ever has. As the movie that put George Lucas on the map and brought him to the industry’s and the world’s attention. As the film that launched the careers of some of the most familiar faces of the 70s and 80s including Richard Dreyfus, Cindy Williams, Paul Le Mat, Charles Martin Smith, Candy Clark, Kathleen Quinlan, Mackenzie Phillips, and some bit part player named Harrison Ford. As the movie that made Wolfman Jack a national celebrity and relaunched the career of Ron Howard. And as the movie whose success made Star Wars possible.

Gary Leva (director, Fog City Mavericks: The Filmmakers of San Francisco): There were a lot of people making “youth films” in the early ‘70s. When I interviewed producer Saul Zaentz for my feature documentary about the San Francisco film community, Fog City Mavericks, he said everybody tried to make American Graffiti, but only George pulled it off.

Joseph McBride (co-screenwriter, Rock ‘n’ Roll High School; author, Steven Spielberg: A Biography): It’s a landmark film in helping change Hollywood (unfortunately not for the better), by playing a major role in turning the once-great American film industry into a marketplace for adolescents and teenagers. American Graffiti was one of the first films I saw in California (Westwood, near the UCLA campus) after moving from Wisconsin in mid-July 1973 to become a screenwriter. I had already found an agent, who had advised me not to write scripts about teenagers and not to write comedies, because he said they wouldn’t sell. So then Graffiti comes out and becomes one of the most profitable films ever made, with a gross of more than $100 million on a production cost of $777,000. I fired that agent. His idiotic advice is classic! The floodgates soon opened on a torrent of dumb youth comedies, which became a flood a few years later as the Reagan period turned Hollywood more conservative and mindless. None of them had the wit or sophisticated style of American Graffiti.

Richard Ravalli (editor, Lucas: His Hollywood Legacy [forthcoming]): From the perspective of teenagers watching cars cruise McHenry Avenue in 1974, some eight months after the release of American Graffiti, it seemed like the local cruise was no big deal. As one was quoted by a New York Times reporter who visited town, “it’s not that much of a big thing anymore,” while another opined that many think of cruising as “dumb and uncool.” Interestingly, the title of Jon Nordheimer’s April 14, 1974 article, “Teen-Age Drivers Still Cruise, but Without That Old Fervor” was changed when it was published in the Modesto Bee three days later, to “Cruising: It Holds the Bright Promise of Adventure.” Perhaps the Bee editors saw something that the teens didn’t. For if you wait a few more years and another film by Modesto’s own George Lucas, the zeitgeist changes. The first mentions of “Graffiti Night” begin to appear, a massive cruise held on McHenry on the weekend after high graduation, a nod to American Graffiti’s storyline. By the end of 1977, talk of using chains and barricades to close off side streets and control cruisers emerge. Such an editorial was published in the Bee on December 6, far away from the “official” Graffiti Night. While the historical relationships may often be forgotten today, both of Lucas’s films, American Graffiti and Star Wars, “put Modesto on the map” and changed the local landscape for years to come. By the 1980s, Graffiti Night was a major Northern California event, drawing cruisers and onlookers from far and wide as Modestans celebrated car culture and the Hollywood icon who made it all shine for them, the cars and the stars. American Graffiti and Lucas’s rising industry profile may not have invented the cruise—the phenomenon was far from just being a West Coast thing in the postwar era—but they certainly affected what Americans thought they were doing when they did cruise. However the 1973 film’s cultural impact is measured, clearly it includes ground zero and the local environs that Lucas sought to preserve and interpret for the future.

Peter Krämer (author, American Graffiti: George Lucas, the New Hollywood and the Baby Boom Generation): I think that it should be remembered as a true American classic, a film that captures two moments in the country’s history: a time of apparently ever-increasing affluence and optimism (the 1950s and early 1960s) and a time of perceived crisis and increasing pessimism (the late 1960s and early 1970s). Even though the film’s action takes place during a single night in the summer of 1962, in a sense the film traces the development of the baby boom generation, those born during the years of exceptionally high birth rates between the 1940s and the 1960s. Through the story of this generation Graffiti maps the history of the country, moving from a vision of excessive consumerism and apparently unlimited growth to a recognition, by the early 1970s, of the limits to growth (as per the title of an influential book from 1972, the year before American Graffiti was released). What is most amazing, perhaps, is that the film achieves this in a wholly unpretentious manner, by nostalgically and compassionately looking back, from the vantage point of 1973, on the very personal trials and tribulations of a bunch of small-town kids in 1962. Admittedly, the broader implications of the film’s story only become apparent when one examines its production history and its reception in the mid-1970s—which is one of the reasons why I felt I had to write a book about all this.

William Kallay (author, The Making of Tron): American Graffiti is a rare film that was able to successfully mix humor and a bittersweet ending. This was the early 1970s when dark themed and gritty cinema ruled. Lucas’ look back on his youth was a departure that was mostly positive, yet still felt raw. He deserves a lot of credit for taking a chance to tell a story that connected directly with those of his generation.

Beverly Gray (author, Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon…and Beyond): American Graffiti arrived in an era when youth audiences were becoming more and more important, and when youthful involvement in national issues (like civil rights and Vietnam) was really changing the nature of the country. Baby Boomers (and there were so many of us) felt a natural connection with the characters in this film. Their behavior on the night of their high school graduation was something with which we could strongly identify. I well remember the gasp that went through the audience when we saw that final-crawl telling us where the central characters would be in ten years’ time. What we learned there seemed to be right on target: Terry the Toad dying in Vietnam and Curt making a new life for himself in Canada, far from the small town where Steve is stuck in a safe but mundane existence that would be explored (but not too effectively) in a sequel.

John Cork (co-author, James Bond Encyclopedia): The way American Graffiti should be remembered is by re-watching it. American Graffiti is one of the most important and influential films ever made. If you had to pick one film that shows the potential of American analog cinema—with no serious visual effects, only minor special effects—real actors, a real story, no spectacle, and virtually nothing that seems to stretch credulity, this is film shows that art form at its highest and most accessible.

CHAPTER 2: GEORGE LUCAS

Gary Leva: As a director, George’s work in Graffiti is really impressive, particularly for a second feature. The camera angles, the natural way the action is staged, the gorgeous shots of the car parked by the lake… it’s all extremely cinematic, and certainly not the norm for what is arguably a teen comedy. What teen comedy ever looked this good, or even aspired to? It’s George’s eye, but we also have to give cinematographer Haskell Wexler credit for making the film look this good on a tiny budget under difficult circumstances.

John Cork: George Lucas has very few director credits, and among those, he made two of the greatest films in cinema history: American Graffiti and Star Wars. I love them both equally for very different reasons.

Ray Morton: Depending purely on your preference and taste (because the quality of both is excellent) it’s either his best film as a director or his second best, with Star Wars filling the other slot.

William Kallay: Lucas was still a very young man when he directed Graffiti. Talk about a second feature film being so well directed and so well made. The man had very little money to work with. Yet with his cast and crew, he managed to pull off a very hilarious and poignant masterpiece, in my opinion. Though Lucas has received grief over the years for his way of directing actors, he clearly showed that he could bring out incredible performances from a very deep and talented cast. To think of the many careers that started as a result of Graffiti is really impressive.

John Cork: George Lucas made films in the 70s through to the mid-80s that so reflect where he was in his life. American Graffiti is about the tough decisions involved in leaving a place you love because you know your future isn’t there. Star Wars is about a kid who leaves home and fulfilled his greatest dream, becomes a legend. Raiders of the Lost Ark is a love letter to the films that shaped Lucas, but also about the dangers of pursuing one’s passion. The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi are about living up to success, and balancing talent, insecurity, tough moral choices, and humanity. On that level, all of these films were intensely personal, but none more so than American Graffiti.

Ray Morton: His work in all areas is superb. The stories came out of his life and he did a great job of dramatizing them for the screen. Lucas also did a brilliant job of recreating the time, place, and feel of the era he was trying to capture on film; the documentary filming style he employed gave the piece incredible verisimilitude; the choreography of the cars during the cruising scenes is quite exciting, as is his spotting of the music; and, despite the hits Lucas can take as a director of actors, he elicits wonderful performances from the entire cast. American Graffiti is a really impressive piece of direction in all respects.

William Kallay: As much as I love the original Star Wars, I loved Lucas’ films such as American Graffiti and THX 1138 for their unapologetic view of the world of their eras. In Graffiti, Lucas obviously had fondness for the people of the small rural town. But he expressed, so well, some of the characters’ desire to break out into the big world. I wonder what other independent films Lucas might have given us outside of the Star Wars universe that were experimental and potentially groundbreaking.

John Cork: All of Lucas’s films of this era are staggeringly great, but if you want to see just how talented he is, American Graffiti is Lucas without ILM, without great pre-visualization artists, before he could call up anyone anywhere and get favors done just because he was George Lucas. This is Lucas when he had to make a period movie for less than a million dollars with a 28-day shooting schedule. The results show the kind of raw talent that he possesses, and it shows the raw talent he possessed that allowed him to create two iconic franchises after the success of American Graffiti.

Peter Krämer: I guess the two most striking insights I gained from all my research on the early career of George Lucas are these: he was not at all destined to become a blockbuster filmmaker, quite on the contrary his interests and ambitions for a long time lay elsewhere; and he was so much more uncompromising than most of his film school peers. In retrospect it appears as a bit of a miracle that this man came to change mainstream cinema forever…. The movies were not his first love in his childhood and youth, perhaps not even the second or third. When he did finally develop a strong interest in movies in his late teens, it was for avant-garde and experimental films, which is what he specialized in at film school. In fact, he imagined that he would later get a film industry job as an animator, cinematographer or editor, while making experimental movies on the side…. But then Francis Coppola convinced him to try his hand at a feature film version of one of his rather unconventional student shorts. It was to be the first production by the newly formed American Zoetrope, a company Coppola set up with funding from Warner Bros. Now, Lucas, who was American Zoetrope’s vice-president, turned his—and Zoetrope’s—debut feature into a formal and stylistic tour de force: a dystopian drama presented in such a way that the in essence quite simple story became largely incomprehensible, while radically simplified, almost abstract sequences alternated with hectic scenes characterized by severe information overload. Warner Bros.’ negative responses to THX 1138 scuppered all further production plans for American Zoetrope, drove Coppola to the brink of bankruptcy and almost ended Lucas’s Hollywood career….. He refused to become a director for hire working on projects he had not himself initiated and developed. Coppola was less choosy and agreed to make a movie based on a recent bestseller for Paramount—and it is a good thing, too, that Coppola was not as uncompromising as Lucas because the result was The Godfather (1972)…. Lucas, however, talked about giving up on feature films altogether, unless he could get funding for making a very personal movie. While a project building on his childhood fascination with Science Fiction serials was also in the running, Lucas’s second production turned out to be a semi-autobiographical film about a group of young people in a small Californian town, some of whom have to make important decisions about the future during one particular night at the end of the summer of 1962…. That summer had been of particular importance for Lucas, because in June 1962, shortly before his high school graduation, he had been in a near-lethal car accident. The accident changed his life—arguably for the better—by turning him away from his obsession with tuning and racing cars and towards getting more of an education. So in the early 1970s, when the direction of his life was once again up for debate, he returned to the summer of 1962 to reflect on the options young people like himself had had, and the decisions they had arrived at…. This nostalgic but not uncritical backwards glance was in tune with the changing outlook of the older baby boomers who, like Lucas, were entering adulthood at a time when there was a pervasive sense of crisis in American society to do with the Vietnam war, a declining economy, concerns about environmental destruction and global overpopulation, and also, especially during the so-called “oil crisis” of 1973/74, with doubts about the security of energy supplies needed to support the American way of life. Older baby-boomers as well as other Americans were inclined to look back at more optimistic times, longingly but also critically, and a wave of nostalgia washed over U.S. culture, making American Graffiti a huge hit and also leading to the massive success of the stage musical (and later film) Grease, of Happy Days and Laverne & Shirley, two television sitcoms featuring lead actors from American Graffiti, and other entertainment forms recreating America in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Joseph McBride: In retrospect, it’s clear that much of the unusual quality of American Graffiti is due to the contributions of his co-writers, Willard Huyck & Gloria Katz. Katz in particular deserves credit for making the women characters in Graffiti—especially Cindy Williams’s Laurie, Candy Clark’s Debbie, and Mackenzie Phillips’s Carol — so well-drawn, real, and memorable. Those qualities—and indeed a good script of any kind—never appeared again in Lucas’s work, although Huyck & Katz did some uncredited writing on the first Star Wars and presumably are responsible for some of the rare funny dialogue sprinkled amidst that mostly crappy script. The most sexist crime in the history of American cinema, however, is how Lucas, over his co-writers’ objections, did not include the female characters of American Graffiti in the epilogue showing the male characters’ fate. That horrible omission makes the film take a dive into downer territory at the end. (Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond hilariously satirized that epilogue at the end of their 1974 film The Front Page, while not neglecting their film’s female characters.) As for Lucas’s direction of Graffiti, he does a remarkably lively and spontaneous job, unlike in any of his other films. Lucas has said he hates directing because he doesn’t like to talk to people, but the film benefits from its fast and snappy shooting schedule, and the quality of the acting in Graffiti presumably is due partly to the script as well as to the self-directing by the actors themselves and the freedom they were given by the taciturn director. A lot of credit for the visual energy and semi-documentary beauty of the film is also due to the great cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who is credited as “visual consultant.” He was in effect the DP but had to commute each day between Los Angeles and northern California while taking over from the credited cameramen, who reportedly were not up to the job…. Another great film craftsman, Walter Murch, deserves tremendous credit as well for his pioneering sound design of the film, which adds so much to the atmosphere and mood of the film. Murch later worked on the restored version of Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil (on which I was a consultant), and he said he was delighted to find that Welles in the famous opening tracking shot had actually invented something he thought he had invented for American Graffiti, the use of diegetic sound of music and other sounds from actual sources to serve as the soundtrack. Universal-International in 1958 replaced Welles’s track for the opening shot with Henry Mancini music, but Murch recreated Welles’s original plan for the soundtrack. Verna Fields and Marcia Lucas did a splendid job editing the film and helping give it the propulsive style that makes it so distinctive.