PART 2: THE INTERVIEW

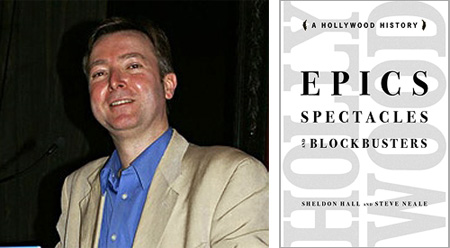

Sheldon Hall is the author (with Steve Neale) of Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010) and is a Senior Lecturer in film studies at Sheffield Hallam University, UK. Other books include Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It—The Making of the Epic Movie (Tomahawk Press, 2005; updated in 2014), and he was the editor (with John Belton and Steve Neale) of Widescreen Worldwide (Indiana University Press, 2010). He was a speaker at the recently-held Jaws 40th Anniversary Symposium at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK.

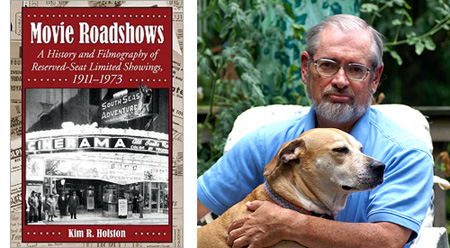

Kim R. Holston is the author of Movie Roadshows: A History and Filmography of Reserved-Seat Limited Showings, 1911-1973 (McFarland, 2013). Kim is a part-time librarian in the Multimedia Department of Chester County Library (Exton, PA) and lives in Wilmington, DE, with his wife Nancy and a menagerie of pets. Other film and performing arts books of his include Starlet (McFarland, 1988), Richard Widmark: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood Press, 1990), Susan Hayward: Her Films and Life (McFarland, 2002), and (with Warren Hope) The Shakespeare Controversy (McFarland, 2nd ed., 2009), and recently Attila’s Sorceress (New Libri Press, 2014) and Naval Gazing: How Revealed Bellybuttons of the 1960s Signaled the End of Movie Cliches Involving Negligees, Men’s Hats and Freshwater Swim Scenes (BearManor Media, 2014). He is presently at work with Tom Winchester on a follow-up to their 1997 book, Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Film Sequels, Series and Remakes.

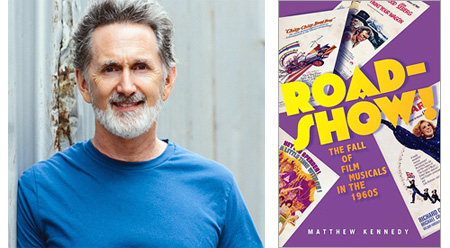

Matthew Kennedy is the author of Roadshow! The Fall of Film Musicals in the 1960s (Oxford University Press, 2014). He is a writer, film historian, and anthropologist living in San Francisco. He has written several other books, including Marie Dressler: A Biography (McFarland, 1999, paperback 2006), Edmund Goulding’s Dark Victory: Hollywood’s Genius Bad Boy (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), and Joan Blondell: A Life between Takes (University Press of Mississippi, 2007). He is film and book critic for the respected Bright Lights Film Journal and currently teaches anthropology and film history at the City College of San Francisco and San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

---

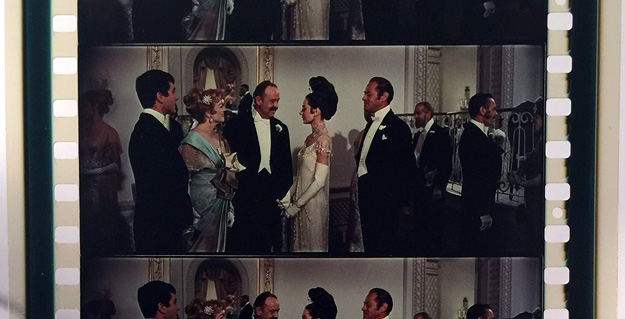

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): In what way is the My Fair Lady motion picture worthy of celebration on its golden anniversary?

Sheldon Hall: As well as being the Best Picture Oscar-winner of 1964, and one of the major box-office hits of the 1960s, it’s a beautifully rendered adaptation of the stage show, preserving Rex Harrison’s definitive performance (as Higgins, as himself).

Kim R. Holston: We can celebrate it as one of the seminal stage musicals transferred lovingly to the screen.

Matthew Kennedy: My Fair Lady is probably the greatest popular smart musical ever made. The melodies soar, the characters endear and engage, and the wit of so much pointed commentary on social class, gender, money, and surface appearances never lapses into self-conscious cleverness. Its greatness comes from Shaw, who remarks on the realities of language, dialects, and identity in a way that hasn’t aged one iota. He was appalled at the idea of turning his Pygmalion into a musical, but if it had to be, lucky for him it had the great and loving treatment of Lerner & Loewe. Also, My Fair Lady preserves Rex Harrison’s immortal Henry Higgins and captured Audrey Hepburn at her peak as a movie star, though I would argue she was most beautiful as an ambassador for UNICEF.

Coate: How is My Fair Lady significant within the musical genre?

Hall: It’s one of the more extreme instances of a trend which had gripped the film musical particularly since the mid-1950s: the dependence on Broadway shows for source material, rather than a book and score created specifically for the screen. Critical tastes tend to favor original creations and to look scathingly on adaptations which aim at fidelity to the source—from one point of view, My Fair Lady does this slavishly and is therefore “stagey,” “theatrical,” etc. But within its own terms of reference the film is skillful and accomplished—it may be theatrical, but so what if it’s good-theatrical, which in my view it is.

Holston: Like other hit musicals created by the likes of Lerner & Loewe, Rodgers & Hammerstein, Rodgers & Hart, every song is distinct and memorable. It was something of a last gasp, set-bound musical but it was given deluxe treatment and worked.

Kennedy: It is Lerner & Loewe’s masterpiece and most beloved work. It solidified the notion that big film musicals were not only viable but nearly fail-safe in the ’60s. That notion would be shattered with Lerner & Loewe’s Camelot in 1967.

Coate: Can you recall your reaction to the first time you saw My Fair Lady?

Hall: I saw it for the first time on its second showing on British television, on BBC1 on New Year’s Eve 1978. I had missed the first showing, on the occasion of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977, because I’d been out of the country at the time. I remember enjoying it very much, and again when it was repeated the following Christmas. I didn’t see My Fair Lady on the big screen until the London press show of the restored version, held at the ABC Shaftesbury Avenue in 1994 (in 35mm because the 70mm print had a fault). I enjoyed the first half so much that I literally skipped to the restroom in the intermission.

Holston: I saw it just before beginning my junior year in high school. It was a roadshow playing at the Stanley in Philadelphia, which not long before had hosted Cleopatra. For the most part, my reaction was very positive. After all, it had so many memorable songs, humor, fine tension and rapport between Rex Harrison and Audrey Hepburn, a sumptuous look. However, I preferred movie musicals to open up the proceedings, in short, to go outside when appropriate. This would find its apotheosis in the following year’s The Sound of Music. So, for me the only real problem with My Fair Lady was the Ascot Gavotte episode. They were supposed to be at a racetrack, but there were no horses! It was stylized. I want to attribute this to Jack Warner or other Warner Bros. chieftains, who, if you examine the 60s musical roadshows filmed by WB, skimped on location shooting. See Gypsy (not even any real street scenes if I recall correctly), Camelot (where were the jousts pictured in the program?), and Finian’s Rainbow (a chintzy backlot farmstead). On the other hand, it has been pointed out that the stiffness of the Ascot Gavotte spectators at the track signifies their ennui. They don’t care if there are horses or not. Perhaps this is discussed in a George Cukor biography.

Kennedy: I remember seeing it from the balcony of the Cascade Theater in Redding, California, in first-run release when I was eight.

Coate: My Fair Lady was voted by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as the Best Picture of 1964. Do you believe My Fair Lady was that year’s best film? If not, which film do you think was the best (or your favorite)?

Hall: My favorite film of 1964 is Zulu but it would be invidious to talk about which film was the “best” of the year. My Fair Lady deserved its awards as the Academy’s choice.

Holston: I have no objection to My Fair Lady winning the Best Picture Academy Award, but my favorite films of ’64 would be Fail-Safe, Dr. Strangelove, Mary Poppins (also set-bound), the third Day-Hudson-Randall comedy Send Me No Flowers, the ultimate guilty pleasure The Horror of Party Beach, and that crazy, glitzy Shirley MacLaine extravaganza, What a Way to Go!

Kennedy: This is tricky. In terms of a splashy movie event, it’s hard to top My Fair Lady, but I would go with Dr. Strangelove as 1964’s best film. My Fair Lady as a film is lacking. There’s very little cinema in it, it’s all big sets, gorgeous costumes, and dull camera work. How much better it might have been with a director unafraid to shape the songs, the performances, and the story around what movies alone can offer. It needs the location filming and lighter touch of Vincente Minnelli’s Gigi, a Lerner & Loewe confection made expressly for film. Producer Jack Warner and director George Cukor decided to record every syllable of the Broadway original, resulting in an overly faithful adaptation that threatens to suffocate the sublime material. There’s limited virtue in My Fair Lady as a film, but plenty as a preservation of a beloved stage musical.

Coate: Where does My Fair Lady rank among Audrey Hepburn’s body of work? And for Rex Harrison? Director George Cukor?

Hall: Enjoyable as I find Hepburn’s performance, the role is not as closely suited to her talents as the best of her work in the 1950s, particularly. For Harrison, it is his archetypal role and performance. My Fair Lady is not Cukor’s most demanding assignment, creatively, but he handles it with the flair and skill of a veteran, which is what was needed.

Holston: Audrey Hepburn has a quality resume and My Fair Lady would be at the top with Roman Holiday. Of course Lady is bigger. I always consider her Natasha in War and Peace as one of the great radiant performances. Breakfast at Tiffany’s? No, it’s good but overrated…. Because Harrison won an Oscar for Lady and it was "Best Picture," that has to be his crowning cinematic achievement. Let’s not forget, however, his Salvation Army officer in Major Barbara, spirit in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, Siamese ruler in Anna and the King of Siam, and Caesar in Cleopatra. He had a presence and is probably underrated as a star…. Cukor’s resume is long, but I’d suspect Adam’s Rib and A Star is Born would be considered at least the equal of Lady.

Coate: My Fair Lady was among only a handful of films released in 1964/65 given the roadshow treatment. In what way was it beneficial for a film to be exhibited as a roadshow?

Hall: The theatrical nature of the roadshow exhibition method was, in this case, ideally suited to the subject and style of the film. Presentation with reserved seats, etc., gave a film a sense of occasion and differentiation from more “ordinary” films, as well as, of course, allowing cinemas to charge, and distributors to receive, higher than average prices.

Holston: It was the golden age of roadshows, and to be a roadshow was to be prestigious. Buying seats in advance made it an event.

Kennedy: Roadshow spelled prestige, increased marketing and publicity, and, so hoped the studios, increased public interest. Expensive, highly anticipated films would open with reserved seats, high ticket prices, a souvenir program, stereo sound, and wide screens. Musical roadshow films usually came with an overture, intermission, and exit music. Exclusive premieres would begin on a handful of screens in big cities, then fan out to wider markets later as “general releases.” The attempt was to create a crackling excitement to new, big-budget movies that approximated the excitement of live theater.

Coate: Would the roadshow exhibition concept be successful if used today?

Hall: Although the same style of presentation was used for reissues of My Fair Lady in the 1970s and 1990s, the slow method of release would not work for most films released today because audiences are accustomed to having quick access to films and because distributors are afraid of the illegal circulation of films through piracy. Even so, the use of IMAX as a special presentation format (with or without 3D) evokes the enhancements of earlier large-screen formats such as Super Panavision 70, and the higher prices charged for such presentations show that “showmanship” of this kind has not been forgotten!

Holston: I doubt it. It is now possible to purchase tickets in advance for the initial showings of some films, but those tickets are not for specific seats and you don’t get deluxe programs and overtures and intermissions. Ever since Billy Jack and Jaws, people are used to seeing a new film immediately somewhere in their vicinity. Instant gratification. Today no one’s going to drive into a city to see a movie that won’t come to the suburbs for months or a year—if it’s successful. That’s what happened with the likes of West Side Story, My Fair Lady and The Sound of Music. Plus, there are hardly any huge art deco movie theaters left in inner cities. As I researched my book I realized that roadshows and movie palaces existed symbiotically. The roadshow depended on palatial theaters—and big premieres. Not to mention concentration of people in cities. Suburbs, cars, and mall theaters helped kill the “experience.”

Kennedy: I don’t think so. Roadshows played hard to get, beginning in big cities on single screens. Today we know most all movies will be available in many forms via the home markets, TV, streaming, etc. Roadshows were based on limited opportunity to see them before they disappeared into the vaults. Opening a huge movie on a handful of screens and withholding it from a larger audience for weeks or months has become too risky. When roadshows were not well received, word of mouth killed them. Now with thousands of screens showing the same “blockbuster” in its opening weekend, audiences are lured in before negative word of mouth spreads. Maybe that’s changing, too. Nowadays audiences text and tweet “this movie sucks” far and wide before its first matinee is over.

Coate: What is the legacy of My Fair Lady?

Hall: The legacy of My Fair Lady is that we have almost as fine a filmic rendition as could be expected of the stage material, given the talents involved (allowing for the fact that, although Julie Andrews would have been better casting, it would have cost her and us Mary Poppins). Every subsequent theater production to some extent lives in its (and especially Harrison’s) shadow, which is some kind of tribute.

Holston: As I previously indicated, it was an immensely popular stage musical preserved properly in its cinematic incarnation.

Kennedy: My Fair Lady was one of the last backlot musicals, made wholly at the Warner Bros. studios. It was to musicals what Ben-Hur was to biblical epics—super sized movie making. In that way, it is very much a period piece, one that fits the tired but true sentiment, “They don’t make ’em like that anymore.” I don’t see that it has any direct descendants, unless we put it in the general class of highly anticipated and very expensive film versions of Broadway musical hits. In that light it is the ancestor of everything from Camelot and Hello, Dolly! to Les Miserables and Into the Woods.

Coate: Thank you, Sheldon, Kim and Matthew, for participating and sharing your thoughts on My Fair Lady on the occasion of its 50th anniversary.

--END--

IMAGES

Copyright/courtesy CBS Home Entertainment, Paramount Home Media, Warner Bros. Pictures

SOURCES/REFERENCES

The primary references for this project were newspaper articles and advertisements archived on microfilm and the periodicals Boxoffice, The Film Daily, The Hollywood Reporter, Motion Picture Herald, and Variety.

SPECIAL THANKS

Jerry Alexander, Jim Barg, Raymond Caple, Nick DiMaggio, Sheldon Hall, Robert A. Harris, Kim R. Holston, Bill Huelbig, Matthew Kennedy, Bill Kretzel, Ronald A. Lee, Mark Lensenmayer, Deborah May, Rick Mitchell, Robert Morrow, Jim Perry, Bob Throop, Joel Weide, Vince Young, and a huge thank-you to all of the librarians who helped with the research for this project.

- Michael Coate